This is not a proof of Cauchy's theorem, but a conceptual interpretation (and, as it happens, an expansion of Cameron Williams's comment): A holomorphic differential form $f(z)\, dz$ on a simply-connected region has a primitive.

On one hand this isn't formally surprising. As we learn in calculus, if $f$ is a continuous function of one variable on some simply-connected region—I mean, on some real interval $I$—then for each $a$ in $I$, the function $F$ defined by

$$

F(x) = \int_{a}^{x} f(t)\, dt

$$

is a primitive of $f$. Particularly, for every closed path $\gamma:[0, 1] \to I$, we have

$$

\int_{\gamma} f(t)\, dt = F\bigl(\gamma(1)\bigr) - F\bigl(\gamma(0)\bigr) = 0

$$

(since $\gamma(0) = \gamma(1)$, cf. Cameron Williams's comment).

So, what's different in the complex setting?

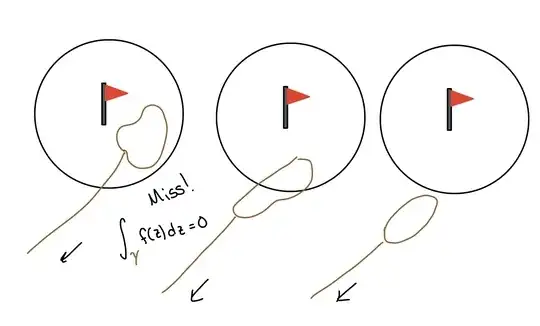

First, continuity of the integrand is not enough; differentiability turns out to be necessary, and locally sufficient. That is, if $R$ is a simply-connected region in the complex plane and $f$ is holomorphic in $R$, then $f(\zeta)\, d\zeta$ has a primitive in $R$ defined by path integration: If we fix a point $z_{0}$ in $R$, then for each $z$ in $R$ and for any two paths $\gamma_{0}$ and $\gamma_{1}$ starting at $z_{0}$ and ending at $z$, Cauchy's theorem guarantees

$$

\int_{\gamma_{0}} f(\zeta)\, d\zeta = \int_{\gamma_{1}} f(\zeta)\, d\zeta.

$$

Since the value does not depend on the choice of path, it's reasonable to denote the common value by

$$

\int_{z_{0}}^{z} f(\zeta)\, d\zeta,

$$

and to define a holomorphic primitive $F$ in $R$ by

$$

F(z) = \int_{z_{0}}^{z} f(\zeta)\, d\zeta.

$$

To emphasize, this is not a proof of Cauchy's theorem, but an intuitive interpretation. It may be worth noting, however, that if we write $z = x + iy$ and $f(z) = u + iv$ with $x$, $y$, $u$, and $v$ real-valued, then

$$

f(z)\, dz = (u + iv)(dx + i\, dy)

= (u\, dx - v\, dy) + i(v\, dx + u\, dy).

$$

When we integrate over the boundary of a region, Green's theorem leads us to consider the integrals of $-v_{x} - u_{y}$ and $u_{x} - v_{y}$. Both integrands vanish identically if and only if the Cauchy-Riemann equations hold in $R$. (In the language of differential forms, $f(z)\, dz$ is closed—has exterior derivative $0$—if and only if $f$ is holomorphic.)

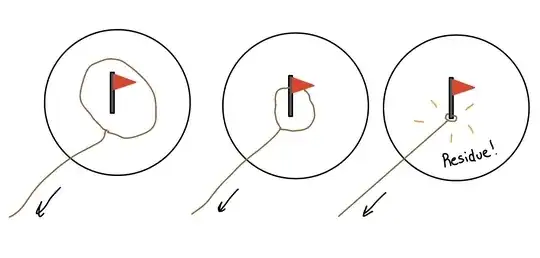

Second, there is a topological aspect to defining primitives. On the real line a point is an obstacle (the complement of a point is disconnected), while in the complex plane a point is not an obstacle (the complement of a point is connected).

Particularly, if $a$ and $b$ are points of a real interval, there is essentially one path from $a$ to $b$. In that respect, it's not surprising that a continuous, one-variable (real) integrand $f(x)\, dx$ has a primitive!

By contrast, there are infinitely many paths between two points of a complex region. As noted above, local path-independence of integrals of $f(z)\, dz$ in $R$ is eqivalent to the Cauchy-Riemann equations in $R$, i.e., to $f$ being holomorphic in $R$.

One remarkable feature of complex analysis is, a holomorphic $1$-form $f(z)\, dz$ in an arbitrary connected region may or may not have a primitive. Let $R = \mathbf{C} \setminus\{0\}$ be the punctured plane and let $n$ be an integer. The power functions $p_{n}(z) = z^{n}$ in $R$ are prototypical: The holomorphic $1$-form $z^{n}\, dz$ has a primitive in $R$ if and only if $n \neq -1$, precisely because if $\gamma$ traces the unit circle once counterclockwise, then

$$

\oint_{\gamma} z^{n}\, dz

= \begin{cases}

0 & n \neq -1, \\

2\pi i & n = -1.

\end{cases}

$$

In the first case, the integral over an arbitrary closed path is $0$, so the integral over an open path depends only on the endpoints. In the second case, integrating around the origin adds a constant so there is no primitive.