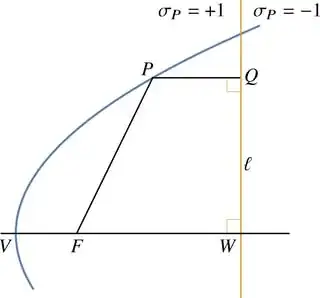

We will be referring to the following figure:

Suppose we are given points $V$ and $F$, and a straight line $\ell$ perpendicular to the line through $V$ and $F$. In the figure, $W$ is the intersection of $\ell$ and the line through $V$ and $F$.

Note that $\ell$ divides the plane into two half-planes, which we will denote (in reference to Fig. 1) as the left and the right half-planes.

The notions of left and right, of course, only make sense in reference to the figure. It is not terribly difficult to make the discussion fully rigorous and independent of any figure. However, I think that, for the purposes of the present question, the additional necessary definitions would be more distracting than helpful. I will, however, provide a sketch of the procedure in Appendix 3.

My question is about the following property/definition of parabola:

The Main Statement

A parabola with a focus at $F$ and a vertex at $V$ is the locus of points $P$ for which

(1) $d(F,\thinspace P) + \sigma_{P}\thinspace d(P,\thinspace\ell)=\text{const.}$,

where

$\sigma_{P} = \begin{cases}+1,\quad \text{if $P$ is in the left half-plane;}\newline +1,\quad\text{if $P$ is on $L$ (though this value is irrelevant, since in this case $d(P,\thinspace L)=0$);}\newline -1\quad\thinspace\thinspace \text{otherwise (i.e., if $P$ is in the right half-plane).}\end{cases}$

Remarks

- This property/definition of the parabola can be easily proven analytically (see Appendix 1), but it is motivated by the fact that a 'parabola is an ellipse with one focal point at infinity' (see Appendix 2).

- There is no restriction on where the line $\ell$ falls relative to $V$ and $F$.

- If $\ell$ is chosen to lie to the left of $V$ and such that $d(W,\thinspace V)=d(V,\thinspace F)$, then $\sigma_{P}=-1$ for all $P$ (since the entire parabola will fall in the right half-plane) and the statement becomes equivalent to the usual definition of the parabola, with $\ell$ the directrix.

- Because we demand $V$ to be a point on the parabola, we see that the constant on the right-hand side of Eq. 1 is $d(V,\thinspace F)+\sigma_{V}\thinspace d(V,\thinspace \ell)$.

My questions

After much googling, I haven't been able to find this property/definition anywhere.

- Is there a source (like a textbook) that gives this property/definition?

- What is a standard way of formulating this property/definition?

- Does this property/definition have a standard name?

Appendix 1: Proof

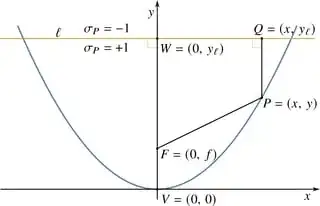

Impose the $x$-$y$ coordinate system as in Fig. 2, so that $V$ is at the origin and $F=(0,\thinspace f)$, $f>0$. It follows that the equation of the parabola is $y=\frac{1}{4f}x^{2}$. The line $\ell$ can be any line parallel to the $x$-axis; its point of intersection with the $y$-axis is $W=(0,\thinspace y_{\ell})$, where $y_{\ell}$ may or may not be positive. Then $\sigma_{P}=+1$ for all points $P$ below or at $\ell$ (i.e., all points $P=(x,\thinspace y)$ such that $y\leqslant y_{\ell}$); otherwise, $\sigma_{P}=-1$.

We always have that $d(F,\thinspace P)=\sqrt{x^{2}+(y-f)^{2}}$ and that $d(P,\thinspace\ell)=|y-y_{\ell}|$. Next, we show that $\sigma_{P}\thinspace d(P,\thinspace\ell)=y_{\ell}-y$ regardless of where $P$ is.

$P$ is either below $\ell$, or at $\ell$, or above $\ell$. If $P$ is below or at $\ell$, then $y\leqslant y_{\ell}$, so $|y-y_{\ell}|=y_{\ell}-y$ and $\sigma_{P}=+1$, so $\sigma_{P}\thinspace d(P,\thinspace\ell)=y_{\ell}-y$. On the other hand, if $P$ is above $\ell$, then $y> y_{\ell}$, so $|y-y_{\ell}|=y-y_{\ell}$ and $\sigma_{P}=-1$, so $\sigma_{P}\thinspace d(P,\thinspace\ell)=y_{\ell}-y$, the same as when $P$ was below or at $\ell$.

Thus, Eq. 1 in all cases reads $\sqrt{x^{2}+(y-f)^{2}}+y_{\ell}-y=\text{const.}$ The requirement that $V=(0,\thinspace 0)$ be on the parabola gives that $\text{const.}=y_{\ell}+f$. Thus, Eq. 1 becomes $\sqrt{x^{2}+(y-f)^{2}}+(y_{\ell}-y)=y_{\ell}+f$, or $\sqrt{x^{2}+(y-f)^{2}}=y+f$. And it is easy to show that $(x,\thinspace y)$ satisfy this equation if and only if $y=\frac{1}{4f}x^{2}$:

Left-to right: start with $\sqrt{x^{2}+(y-f)^{2}}=y+f$. Squaring both sides and simplifying, we get $x^2-2fy=2fy$, which is equivalent to $y=\frac{1}{4f}x^{2}$.

Right-to-left: assume $y=\frac{1}{4f}x^{2}$. In $\sqrt{x^{2}+(y-f)^{2}}$, replace $x^{2}$ by $4fy$. We get $\sqrt{x^{2}+(y-f)^{2}}=\sqrt{4fy+(y-f)^{2}}=\sqrt{(y+f)^{2}}=|y+f|$. Since $f>0$ and $y=\frac{1}{4f}x^{2}$ it follows that $y\geqslant 0$; so $y+f>0$, so $|y+f|=y+f$, and so we have proven that if $y=\frac{1}{4f}x^{2}$, then $\sqrt{x^{2}+(y-f)^{2}}=y+f$. $\square$

Appendix 2: Intuition

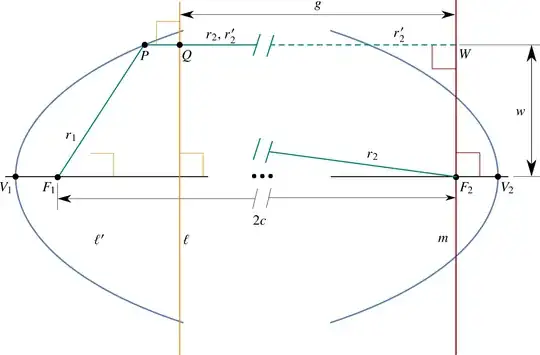

Consider an ellipse with vertices at $V_{1}$ and $V_{2}$ and foci at $F_{1}$ and $F_{2}$ (so that $d(V_{1},\thinspace V_{2})=2a$ and $d(F_{1},\thinspace F_{2})=2c$, with $b=\sqrt{a^{2}-c^{2}}$). All four of these points lie on a line, the axis of the ellipse. We can produce a parabola with a vertex at $V=V_{1}$ and focus at $F=F_{1}$ by sending $F_{2}$ to infinity while keeping the distance $d(V_{1},\thinspace F_{1})=a-c$ constant; let's call this the parabolic limit.

Referring to Fig. 3, we have that $d(F_{1},\thinspace P)=r_{1}$, $d(F_{2},\thinspace P)=r_{2}$, and of course $r_{1}+r_{2}=2a$ (we will use the symbol $r_{1}$ to denote both the line segment $\overline{F_{1}P}$ and its length, and similarly for all other labeled distances; it will always be clear from context whether I mean the line segment or its length).

Let $m$ be the line through $F_{2}$ perpendicular to the axis, and let $r_{2}'=d(P,\thinspace m)$. Now consider what happens as $2c$ becomes larger and larger while we keep the following unchanged: $V_{1}$, $F_{1}$, and the orthogonal projection of $P$ onto the axis, i.e., the intersection of the axis and the line through $P$ perpendicular to the axis. (I don't want the point $P$ to be escaping to infinity in the limit.)

In this limit, the lengths $r_{2}$ and $r_{2}'$ become indistinguishable: $r_{2}' =\sqrt{(r_{2})^{2}-w^{2}}= r_{2}\sqrt{1+\left(\frac{w}{r_{2}}\right)^{2}}\approx r_{2}$, since $\frac{w}{r_{2}}$ goes to zero in the limit ($w=d(F_{2},\thinspace W)$). (Also note that near $F_{2}$, the line segment $r_{2}$ falls closer and closer to the axis, and so becomes closer and closer to being parallel to the line segment $r_{2}'$.) So, in the limit, instead of $r_{1}+r_{2}=2a$, we can write $r_{1}+r_{2}'=2a$.

Now we note that, in the limit, both $r_{2}'$ and $2a$ grow without bound, while $r_{1}$ approaches a finite limit. We would like to replace $r_{1}+r_{2}'=2a$ by an equation all of whose terms remain finite in the limit.

To accomplish this, introduce a line $\ell$ to the right of $P$, such that $\ell$ remains stationary in the limit. We note that the distance $g$ between $\ell$ and $m$ is the same for all points $P$ to the left of $\ell$. Therefore, for such points, $r_{2}'=g+d(P,\thinspace Q)$ (note that $d(P,\thinspace \ell)=d(P,\thinspace Q)$ by definition). Thus, $r_{1}+r_{2}'=2a$ if and only if $r_{1}+d(P,\thinspace Q)=2a-g$. Note that $2a-g$ remains finite in the limit. Indeed, considering the case when $P=V_{1}$, we get that $2a-g=d(V,\thinspace F_{1})+d(V,\thinspace\ell)$, which is unaffected by the limit. So for all points $P$ to the left of $\ell$, in the parabolic limit, we get $r_{1}+d(P,\thinspace \ell)=\text{const.}$

What about points $P$ to the right of $\ell$? For them, we have $r_{2}'=g-d(P,\thinspace \ell)$. So, for all points, we have $r_{2}'=g+\sigma_{P}\thinspace d(P,\thinspace \ell)$, where $\sigma_{P}=+1$ if $P$ is to the left of $\ell$, and $\sigma_{P}=-1$ if $P$ is to the right of $\ell$.

If $P$ is on $\ell$, then $d(P,\thinspace \ell)=0$, and it does not matter what $\sigma_{P}$ is. For completeness, however, let us define $\sigma_{P}=+1$ in that case, too.

Thus we obtain that, in the limit, for all points $P$ we have $r_{1}+\sigma_{P}\thinspace d(P,\thinspace \ell)=\text{const.}$, which is equivalent to Eq. 1 from the Main Statement. Note that it does not matter where $\ell$ is placed, as long as it is perpendicular to the axis and unaffected by the limit.

Appenfix 3: defining the positive and negative half-planes without resorting to figures

Although the procedure does not depend on any figure, you may nevertheless find it helpful, as you read, to refer to Fig. 1. The procedure described here should end up defining the left half-plane in that figure as the positive one.

We start by considering an $\ell$ such that $V$ and $F$ are in the same half-plane (just as in the figure). Consider the half-line that is the intersection of the half-plane that contains $V$ and $F$, and the axis through $V$ and $F$. If $F$ is between $V$ and $W$, then we say that the half-line points in the positive direction; otherwise, it points in the negative direction. For short, we say that the half-line that points in the positive direction is the positive half-line.

Now that we have one half-line along the axis for which we can define the direction, we can use it to define the direction of all half-lines along the same axis. The procedure is described here.

Now that we have defined the directions of all half-lines along the axis, we continue as follows. Given an arbitrary $\ell$ (which, as usual, defines two half-planes, but which, relative to $F$ and $V$, can fall anywhere, for example between $F$ and $V$), the positive half-plane is the one that contains the positive half-line that begins at $W$.

My questions, again

- Is there a source (like a textbook) that gives this property/definition?

- What is a standard way of formulating this property/definition?

- Does this property/definition have a standard name?