Before starting, I need to make a confession: up to the very end, I hoped that someone could write this answer instead of me. That's because this story deserves to be explained and shared, but even this case is all but straightforward. By "tractable", I mean that there exists someone who could likely pass an open book exam on most of it (in the sense of this interesting blog post). But it would be a long exam!

Anyway, I'll first sketch how the argument goes (please pay no heed to the notation which may seem a bit too much - I only wrote it like this because it's the standard), then comment some more before going into detail.

This is going to be a very long answer. Feel free to skip over what you don't need or don't understand.

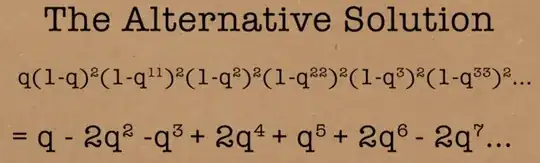

We identify $g_0(q)=q\left(\prod_{n \geq 1}{(1-q^n)(1-q^{11n})}\right)^2=\sum_{n \geq 1}{a_nq^n}$ as an element of some vector space $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_1(11))$ of holomorphic functions on the upper half-plane $\mathbb{H}$.

We identify Hecke operators $T_n$ (for every integer $n \geq 1$) acting on $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_1(11))$.

We show that $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_1(11))$ has dimension one over $\mathbb{C}$.

We deduce that $T_ng_0=a_ng_0$ for all $n \geq 1$ (yes, that's the same $a_n$).

We construct a complex elliptic curve $X_1(11)$ with actions of Hecke operators $T_n$ such that its space of holomorphic differentials identifies (including the action of $T_n$) with $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_1(11))$.

In particular, $T_n$ acts on $X_1(11)$ acts as multiplication by $a_n$.

We algebraize that setting: we construct an elliptic curve $X_1(11)_{\mathbb{Q}}$ over $\mathbb{Q}$ with good reduction outside $11$ (it has a "nice" [smooth] equation with integer coefficients that stays nice when you reduce it modulo any prime $p \neq 11$), with algebraic actions of the $T_n$, such that when we go back to complex numbers, we recover the construction of 5).

We show that $X_1(11)_{\mathbb{Q}}$ has the equation $y^2+y=x^3-x^2$.

In particular, $T_n$ acts on $X_1(11)_{\mathbb{Q}}$ as the multiplication by $a_n$.

Let $p \neq 11$ be a prime number. Then $T_p$ can be made to act on the reduction $X_1(11)_{\mathbb{F}_p}$ of the elliptic curve $X_1(11)_{\mathbb{Q}}$ (same as before: take the nice equation, such as $y^2+y=x^3-x^2$, and just consider it modulo $p$).

One links this reduction mod $p$ of $T_p$ to the action of the Frobenius $\varphi$ (I'll get to what $\varphi$ is) and shows that $T_p=\varphi+p\varphi^{-1}$. This is the Eichler-Shimura relation, possibly the only part of the picture (in this case) not known in 1940.

It follows that (on the reduction of $X_1(11)_{\mathbb{F}_p}$ modulo $p$) $\varphi^2-a_p\varphi+p=0$. This, in turn, implies that $a_p$ is the normalized number of the points modulo $p$ on $X_1(11)_{\mathbb{Q}}$, QED.

If you replace $11$ with another integer $N$, surprisingly few things change in this strategy:

a) The explicit computations (steps 1, 3, 8) cannot be done in general, of course. Still, if you know what modular form $g$ you started from and are given a specific value of $N$, you can identify the elliptic curve using the fact that it has good reduction at every prime not dividing $N$ and given the first few coefficients of $g$. I'm not sure how it's done, but it can often be safely delegated to the LMFDB.

b) One replaces $\Gamma_1$ and $X_1$ with $\Gamma_0$ and $X_0$.

c) The Hecke operators (at $n$ coprime to $N$, at any rate) can be shown to pairwise commute and be self-adjoint, hence there is a basis of $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_0(N))$ made with eigenvectors for these Hecke operators.

d) In fact, there is a sub-basis made with "new" elements, which are in particular eigenvector of all the Hecke operators. So the procedure starts from a vector in this basis $\sum_{n \geq 1}{a_nq^n} \in \mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_0(N))$ where $a_1=1$ and the $a_n$ are integers.

e) In general, $X_0(N)$ is not an elliptic curve and does not have endomorphisms. The Hecke operators $T_n$ act on its Jacobian $J_0(N)$ (in a first approximation, it is the smallest complex torus containing $X_0(N)$; it can also be algebraized), and the elliptic curve that we end up considering is the largest quotient of $J_0(N)$ where $T_n$ acts by multiplication by $a_n$.

f) One should prove that this quotient has dimension one. It is not trivial in general and is known as a "multiplicity one" theorem.

Note that all of these arguments are far easier than the reverse direction, that is, attributing a modular form to an elliptic curve over $\mathbb{Q}$. This takes a lot more effort, as I'm sure was told in the video (see the blog post again for a little bit of name-dropping).

Anyway, let's get into detail. All of what I'm going to explain is well-known; a good reference for most of it would be Diamond-Shurman, A First Course in Modular Forms. The specific part about elliptic curves is probably better discussed on a book which is specifically on this topic.

Modular forms

Let $\mathbb{H} \subset \mathbb{C}$ be the (open) upper half plane. A matrix $M=\begin{pmatrix}a & b\\c &d\end{pmatrix} \in GL_2(\mathbb{R})$ with positive determinant acts on $\mathbb{H}$ by $M \cdot z=\frac{az+b}{cz+d}$. This defines a group action of $GL_2^+(\mathbb{R})$ on $\mathbb{H}$.

We let $\mathscr{H}$ be the space of holomorphic functions on $\mathbb{H}$; given an integer $k$, there is a right action "of weight $k$" on $\mathscr{H}$ by the following:

$$\left[f \mid_k \begin{pmatrix}a & b\\c & d\end{pmatrix}\right](z)=\frac{(ad-bc)^{k-1}}{(cz+d)^k}f\left(\frac{az+b}{cz+d}\right)$$

Now, a congruence subgroup is a subgroup $\Gamma$ of $SL_2(\mathbb{Z})$ containing some $\Gamma(N)$ for some $N \geq 1$, where $$\Gamma(N)=\ker\left[SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) \rightarrow SL_2(\mathbb{Z}/N\mathbb{Z})\right]=\{M \in SL_2(\mathbb{Z}),\, M \equiv I_2 \pmod{N}\}.$$

The smallest such $N$ is commonly (and somewhat informally) referred to as the level of the congruence subgroup.

Examples of congruence subgroups are the subgroup $\Gamma_0(N) \leq SL_2(\mathbb{Z})$ of matrices whose reduction mod $N$ is upper-triangular, and the subgroup $\Gamma_1(N) \leq \Gamma_0(N)$ of matrices congruent mod $N$ to $\begin{pmatrix} 1 & \ast\\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}$.

Suppose that $f \in \mathscr{H}$ is stable under the weight $k$ action of some congruence subgroup. It can be checked that:

- For any $\gamma \in GL_2^+(\mathbb{Q})$, the same holds for $f \mid_k \gamma$.

- There is some $N \geq 1$ such that $f(z+N)=f(z)$ (because $\begin{pmatrix} 1 & N \\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}$ is in the congruence subgroup for some $N \geq 1$).

The 2) implies in particular that we can write $f(z)=\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty}{a_n(f)e^{2i\pi nz/N}}$ for some complex numbers $a_n$. This is the $q$-expansion of $f$.

It is named like this because we usually note $q^{a}=e^{2i\pi az} \in \mathscr{H}$ for any rational number $a$: it is a holomorphic function from $\mathbb{H}$ to the open unit disk. Note that as the imaginary part of $z$ goes to infinity, $q^a \rightarrow 0$ uniformly.

Now, given an integer $k \in \mathbb{Z}$ and a congruence subgroup $\Gamma$, we denote by $\mathcal{M}_k(\Gamma)$ (resp. $\mathcal{S}_k(\Gamma)$) the subspace of functions $f \in \mathscr{H}$ such that

- they are invariant under the weight $k$ action of $\Gamma$,

- for any $\gamma \in SL_2(\mathbb{Z})$, if the $q$-expansion of $f \mid_k \gamma$ is given by a sum $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}{a_nq^{n/N}}$ for some $N \geq 1$ (resp. a sum $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}{a_nq^{n/N}}$).

$\mathcal{M}_k(\Gamma)$ is the space of modular forms of weight $k$ for $\Gamma$, while $\mathcal{S}_k(\Gamma)$ is the space of cusp forms of weight $k$ for $\Gamma$.

Finally, we can define the set $X(\Gamma)$ as the quotient $\Gamma \backslash (\mathbb{H} \cup \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Q}))$ (it is easy to see how $\Gamma$ acts on $\mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{Q})$; it is not so difficult to see that the action has finitely many orbits).

It is not too difficult to see how this inherits a complex structure at points whose stabilizer in $\Gamma$ is trivial. A bit of technical work is needed to give this a topology and exhibit a nice enough complex structure the finite remaining $\Gamma$-orbits.

In particular, we end up with the following nice properties:

- the projection mod $\Gamma$: $\mathbb{H} \rightarrow X(\Gamma)$ is holomorphic,

- $X(\Gamma)$ is compact.

It is then somewhat formal to show that the space of holomorphic differential forms on $X(\Gamma)$ identifies with $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma)$. We let $X_1(N)=X(\Gamma_1(N))$ and $X_0(N)=X(\Gamma_0(N))$.

We will also refer to the points of $X(\Gamma)$ that do not come from $\mathbb{H}$ as \emph{cusps}.

Fun with small level:

Given an even $k \geq 4$, you can define the Eisenstein series $$E_k(z)=\frac{1}{2\zeta(k)}\sum_{(c,d) \in \mathbb{Z}^2\backslash \{0\}}{(cz+d)^{-k}},$$ which turns out to be in $\mathcal{M}_k(SL_2(\mathbb{Z})$ with $q$-expansion $1-\frac{2k}{B_k}\sum_{n \geq 1}{\left(\sum_{d \mid n}{d^{k-1}}\right)q^n}$, where the $B_k$ are Bernoulli numbers.

But in fact, we can also consider the series $E_2(z) \in \mathscr{H}$ with the same $q$-expansion when replacing $k=2$. A rather nasty computation (because we've lost locally normal convergence of the series) shows that we in fact have $E_2 \mid_2\begin{pmatrix}0 & -1\\1 & 0\end{pmatrix}(z)=E_2(z)+\frac{12}{2i\pi\tau}$.

Now define $\eta(z)=q^{1/24}\prod_{n \geq 1}{(1-q^n)}$: you can check that $\frac{\eta'}{\eta}=\frac{i\pi}{12}E_2$, from which it follows that

$$\eta\left(\frac{-1}{\tau}\right)=\sqrt{\frac{\tau}{i}}\eta(\tau).$$

The computation I alluded to enables you in fact to compute $E_2 \mid_2\gamma$ for any $\gamma \in SL_2(\mathbb{Z})$ and you can get from this an idea of what happens to $\eta$.

The upshot is that $\eta(z)^2\eta(11z)^2=g_0(q)$ can be checked to be in $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_1(11))$.

Next, we want to show that $X_1(11)$ is an elliptic curve, or equivalently that $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_1(11))$ has dimension $1$.

To do this, we consider the projection $X_1(11) \rightarrow X(SL_2(\mathbb{Z})$ and apply the Riemann-Hurwitz formula; by checking carefully where this projection ramifies, we find that it is enough to show that $X(SL_2(\mathbb{Z}))$ has genus zero.

This can be done using the $j$-invariant map: it is the map $j: \mathbb{H}/SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) \rightarrow \mathbb{C}$ defined as $\frac{1728E_4^3}{E_4^3-E_6^2}$. I invite you to check that its $q$-expansion $j(z)=\frac{1}{q}+744+196884q+\ldots$.

The point is that $j$ extends to a map $J: X(SL_2(\mathbb{Z}) \rightarrow \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{C})$. You can check that $\infty = SL_2(\mathbb{Z})[1:0] \in X(SL_2(\mathbb{Z})$ is not a ramification point of this map and that it is the only pre-image of $\infty=[1:0] \in \mathbb{P}^1(\mathbb{C})$: it follows from standard Riemann surface theory that $J$ is an isomorphism and in particular $X(SL_2(\mathbb{Z}))$ has genus zero.

For future reference, I will note here that you can do the same trick with $X_0(11) \rightarrow SL_2(\mathbb{Z})$, deduce that it is also an elliptic curve, and hence $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_0(11))$ also has dimension $1$ and is contained in the complex line $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_1(11))$: hence $\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_1(11))=\mathcal{S}_2(\Gamma_0(11))$.

Hecke operators

I am, in this case, going to work over $\Gamma_0(11)$ (the logic is the same than for $\Gamma_1(11)$, but one needs to introduce additional operators calld diamonds which do nothing in this case).

Let $p \neq 11$ be a prime. We define the Hecke operator $T_p$ by the following formula: if $f \in \mathcal{M}_k(\Gamma_0(11))$, $T_pf = \sum_{m=0}^{p-1}{f \mid_k \begin{pmatrix} 1 & m\\0 & p\end{pmatrix}}+f \mid_k \begin{pmatrix}p & 0\\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}$.

We then define $T_{p^n}$ for $n \geq 2$ by $T_{p^n}=T_pT_{p^{n-1}}-p^{k-1}T_{p^{n-2}}$ (with $T_1$ being the identity).

For $p=11$, we remove the term $f \mid_k \begin{pmatrix}p & 0\\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}$ from the formula for $T_p$ and take $T_{p^n}=T_p^n$.

Why do these formulas make sense? The key insight is the following (for $p \neq 11$ prime; the case $p=11$ is similar, the case of prime powers is, in a way, more of a convenience): let $\Delta_p$ be the space of matrices $2 \times 2$ with integral entries, determinant $p$, and that are upper triangular mod $11$.

Then $\Delta_p=\Gamma_0(11)\begin{pmatrix}1 & 0\\0 & p\end{pmatrix}\Gamma_0(p)$ (so it is stable under right multiplication by $\Gamma_0(11)$), and the matrices $\begin{pmatrix}1 & m\\0 & p\end{pmatrix}$, $\begin{pmatrix}p & 0\\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}$ are representatives of the cosets for the action of $\Gamma_0(p)$ on $\Delta_p$ by left multiplication.

We can actually compute the action of the $T_p$ on a $q$-expansion, and it turns out that the $T_p$ for prime $p$ all pairwise commute. In particular, given an integer $n \geq 1$, we can define $T_n=\prod_q{T_q}$, where $q$ runs over the prime powers $q$ dividing $n$ with $q$ coprime to $n/q$.

The $T_n$ all commute, and one can check that if $f \in \mathcal{S}_k(\Gamma_0(11))$ has $q$-expansion $\sum_{n \geq 1}{a_nq^n}$, the first term in the $q$-expansion of $T_nf$ is $a_n$.

In particular, if $k=2$ and $a_1=1$ (by dimension, we then know that $f=g_0$ is the only possibility!) then (since we're on a complex line) $T_ng_0=a_ng_0$ (where the $a_n$ are defined as in the beginning of this answer).

In order to discuss how the $T_n$ act on $X_0(11)$ and then to bring all this over $\mathbb{Q}$, I am only going to discuss this in very rough terms.

In that same blog post, Kevin Buzzard argues that there lies a minefield of unsexy technical issues that get in the way of very intuitive results, and I'm likely to get something wrong (besides likely losing everyone, of course) if I become too specific.

Let $\tau \in \mathbb{H}$, you can then consider the holomorphic elliptic curve $E_{\tau}=\mathbb{C}/(\mathbb{Z}\oplus\tau\mathbb{Z})$ over $\mathbb{C}$.

You can then check that $E_{\tau}$ and $E_{\tau'}$ are isomorphic iff $\tau' \in SL_2(\mathbb{Z})\tau$.

Now, consider the point $P_{\tau} \in E_{\tau}$ (resp. the subgroup $C_{\tau} \subset E_{\tau}$) of order $11$ given by the class $1/11$.

It then turns out that the pairs $(E_{\tau},P_{\tau}),(E_{\tau'},P_{\tau'})$ (resp. $(E_{\tau},C_{\tau}),(E_{\tau'},C_{\tau'})$) are isomorphic iff $\tau' \in \Gamma_1(11)\tau$ (resp. $\tau'\in \Gamma_0(11)\tau$).

In other words, we found a new interpretation for $\Gamma_0(11)\backslash \mathbb{H}$ and $\Gamma_1(11)\backslash \mathbb{H}$, as a moduli space, that is, a space of isomorphism classes of "certain things".

It turns out that the Hecke operators of prime index $p \neq 11$ also have an interpretation in this viewpoint. For instance, you can check that for "almost all" $\tau \in \mathbb{H}$, the set of the $\begin{pmatrix} 1 & m\\0 & p\end{pmatrix}\tau$ and $\begin{pmatrix}p & 0\\0 & 1\end{pmatrix}\tau$ is exactly the set of $\Gamma_0(11)$-orbits of $\tau'$ such that there exists a surjective morphism with cyclic kernel of order $p$ (a cyclic isogeny of degree $p$) $E_{\tau} \rightarrow E_{\tau'}$ mapping $C_{\tau}$ to $C_{\tau'}$.

This makes them (after some work at the remaining points, as well as the cusps) into well-defined correspondences (some kind of nice of multi-valued functions) on $X_0(11)$ (and with small adjustments, on $X_1(11)$). But since $X_0(11)$ is an elliptic curve, we can simply consider the sum of all the images of a point, this gives up a bona fide morphism of $X_0(11)$ into itself (the same goes for $X_1(11)$). Because $T_p$ acts as $a_p$ on the holomorphic differentials, this morphism must be in fact equal to multiplication by $a_p$.

The idea behind putting everything back over $\mathbb{Q}$ is the following: we have a complex equation (the elliptic curve equation defining $X_0(11)$) whose solutions parametrize over $\mathbb{C}$ elliptic curves with a cyclic subgroup of order $11$.

But why should this equation be complex in nature? Can this problem not be asked over any other field of coefficients (eg the rationals)? Why should the answer be any different?

It turns out indeed that the solution is not different. It involves some nontrivial algebraic geometry, but we can in fact prove that there is an "algebraic space" (a smooth proper scheme, which I'll still call $X_0(11)$ because they're the same thing as above) defined by "nice equations" over the ring $\mathbb{Z}[1/11]$ such that, for any field $k$ where $11$ is invertible,

the $k$-rational points of this space (aka the solutions of these "nice equations" over $k$) are either cusps (which still have a very precise description), or the isomorphism classes of pairs $(E,C)$, where $E$ is an elliptic curve over $k$ and $C$ is a cyclic subgroup of order $11$.

It turns out that this formalism is powerful enough to incorporate the Hecke operators as well (with their interpretation as above). So now, you should keep in mind that all the nice geometric objects we discussed earlier come, in fact, from complex solutions of polynomial equations over $\mathbb{Z}[1/11]$.

Of course, this whole approach also works for $X_1(11)$.

I'd like to mention that this case is simple enough that there may be a feasible computational way of proving that $y^2+y=x^3-x^2$ is the equation that governs this very abstract instance of $X_1(11)$. I don't know how it would be done.

One possible strategy might be to compute the field of meromorphic functions on the complex $X_1(11)$ defined above, and exhibit functions $X(z),Y(z)$ that are regular everywhere except at some point (the class of $[1:0]$, typically), and have poles of order $2$ and $3$ respectively at this point. By the complex theory of elliptic curves (most importantly, the Riemann-Roch formula), you should be able to show that these functions $X(z),Y(z)$ satisfy a Weierstrass equation which defines the elliptic curve, and modify them slightly so that this equation becomes $Y^2+Y=X^3-X^2$.

All of the above should be enough elaboration on Steps 1-8. Then Step 9 and 10 follow essentially from the formalism.

Step 9: $T_n$ act on [this abstract object] defined over $\mathbb{Z}[1/11]$, and they become [some simple thing] when we go to $\mathbb{C}$. This means they always had to be [the simple thing]!

Step 10: because we have "good reduction", it means that we can also always find "good equations" defining $T_p$ so that they can also be reduced mod $p$.

Now, I'm going to discuss a bit what the Frobenius is (to hint at what Step 11 and 12 mean).

Let $p$ be a prime and $F$ be a finite field of characteristic $p$. You can check that $\varphi: z \longmapsto z^p$ is a field automorphism of $F$.

So, for instance, if you consider the space of solutions in $F$ of, say, $y^2+y=x^3-x^2$, then you can apply $\varphi$ to a given solution $(x,y)$ and find another one: $(\varphi(x),\varphi(y))=(x^p,y^p)$. Note that the solution will be the same iff $x,y \in \mathbb{F}_p$.

In the case of the elliptic curve $y^2+y=x^3-x^2$ over $\mathbb{F}_p$, it's even better, because the addition of points is defined by equations that are rational fractions over $\mathbb{F}_p$: it means that $\varphi$ induces a group endomorphism of the solutions of the elliptic curve!

To prove the Eichler-Shimura relation, the idea is to find a sufficiently precise interpretation of what $T_p$ does to elliptic curves (remember that the solutions to $y^2+y=x^3-x^2$ represent some elliptic curves), so that it still makes sense in characteristic $p$.

This is a subtle issue. Indeed, elliptic curves over $\mathbb{C}$ have $p+1$ cyclic subgroups of order $p$, but the structure of $p$-torsion of elliptic curves in characteristic $p$ is more delicate to understand: there can be $1$ or $p$ points of $p$-torsion, but they will be, in a certain sense, "thicker".

Anyway, the final step.

With what we've seen so far, we know that on the elliptic curve $y^2-y=x^3-x^2$ mod $p \neq 11$, we have $\varphi^2-a_p\varphi+p=0$ (this holds for all solutions, not just the ones in $\mathbb{F}_p$ but for all the solutions in field extensions as well).

Let $p-b_p$ denote the number of solutions to $y^2-y=x^3-x^2$ in $\mathbb{F}_p$. It follows from the theory of elliptic curves that $|b_p| < 2\sqrt{p}$ (this is the Hasse bound) and that $\varphi^2-b_p\varphi+p=0$.

Why? The idea is that morphisms $u: E \rightarrow E$ (where $E$ is our elliptic curve) have a "transpose" $\hat{u}: E \rightarrow E$, such that $u \longmapsto \hat{u}$ is additive, respects the identity, and that $u\hat{u}=\hat{u}u$ is the degree of $u$ (in so-called separable cases, the number of points in the kernel).

It turns out that $1-\varphi$ is always separable, and its kernel is the solutions of the elliptic curve equation in $\mathbb{F}_p$, hence it has degree $p+1-b_p$ (we need to count the point at infinity!).

On the other hand, $\varphi$ has degree $p$ (because it's essentially $z \longmapsto z^p$). It follows in particular that $\varphi+\hat{\varphi}=b_p$, hence $\varphi^2-b_p\varphi+p=(\varphi-\varphi)(\varphi-\hat{\varphi})=0$.

To prove the bound on $b_p$, note that for any integers $m,n$, $m^2\varphi^2-mnb_p\varphi+n^2p=(m\varphi-n)(\widehat{m\varphi-n})$is the degree of something hence non-negative. Thus the polynomial $X^2-b_pX+p$ is non-negative at all rationals, hence it is non-negative. It cannot have a double root since $b_p$ is an integer and $2\sqrt{p}$ isn't. So the polynomial $X^2-b_pX+p$ has no real root, thus $|b_p| < 2\sqrt{p}$.

Now, $(a_p-b_p)\varphi=(\varphi^2-b_p\varphi+p)-(\varphi^2-a_p\varphi+p)=0$. Since $\varphi$ is clearly surjective, it follows that $a_p=b_p$. Thus, we are done.