For the first two matrices, there are quick tricks that are applicable to $3 \times 3$ matrices (and for the first more generally) by which we can come to the conclusion that the matrices is diagonal.

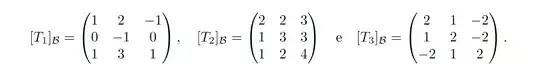

For the first matrix $A = [T_1]_{\mathcal B}$, the key is to notice that the matrix has a row/column consisting of zeros except on the diagonal. In particular, the second row has zeros except for the $-1$ on the diagonal. By expanding $\det(A - \lambda I)$ with a Laplace expansion along the second row, we find that

$$

\det (A - \lambda I) = -0 \det\pmatrix{?&?\\?&?} + (-1 - \lambda) \det \pmatrix{1 - \lambda & -1\\1 & 1 - \lambda} - 0 \det \pmatrix{?&?\\?&?}\\

= (-1 - \lambda)\pmatrix{1 - \lambda & -1\\1 & 1 - \lambda}.

$$

So, our characteristic polynomial is $(-1-\lambda)$ multiplied by the characteristic polynomial of the $2 \times 2$ matrix $\pmatrix{1 & -1\\1 & 1}$, which means that the eigenvalues of $A$ are $-1$ together with the eigenvalues of this smaller matrix. If we recognize this $2 \times 2$ matrix as a matrix of the form $\pmatrix{a & -b\\b & a}$, then we can quickly ascertain that its eigenvalues are $a \pm bi$, which is to say $1 \pm i$. Thus, $A$ has distinct eigenvalues $-1, 1-i, 1+i$. So, $A$ is diagonalizable.

The second matrix $B = [T_2]_{\mathcal B}$ can be written as a rank-1 matrix added to a multiple of the identity. That is, we can write $B = uv^T + tI$ for some column-vectors $u,v$ and scalar $t$. Such a matrix is diagonalizable if and only if $uv^T$ is diagonalizable.

To check whether $B$ is of this form, we could begin by "blanking out" the diagonal entries. Consider the matrix

$$

\pmatrix{?&2&3\\

1&?&3\\

1&2&?}.

$$

Is there a way that I can fill in the blanks in order to make this matrix rank-1? Yes: writing in the entries $1,2,3$ means that I have the same row repeated $3$ times. Can we get these entries by replacing $B$ with $B + tI$? Yes: the rank-1 matrix we described is $B - I$.

So, $B$ has the same eigenvectors as the rank-1 matrix

$$

B - I = \pmatrix{1&2&3\\

1&2&3\\

1&2&3},

$$

so it suffices to determine whether $B-I$ is diagonalizable. $B-I$ has an eigenvalue of $0$ with multiplicity $2$, the question is simply whether $B$ has a non-zero eigenvalue (which would necessarily have a one-dimensional associated eigenspace). In order to check whether this is the case, calculate the trace of $B - I$, which is the sum of its eigenvalues. We calculate

$$

\operatorname{tr}(B - I) = 1 + 2 + 3 = 6.

$$

So, $B-I$ has an eigenvalue of $6$. So, $B - I$ is diagonalizable.

An alternative approach: as the other answer notes, we can check common candidates for the eigenvectors. A matrix will have $(1,1,1)$ as an eigenvector if (and only if) all of its rows have the same sum. $B$ has an $(1,1,1)$ as an eigenvector, and the associated eigenvalue is $7$.

One way to make use of this eigenvalue/eigenvector pair is to get the characteristic polynomial of $B- 7I$. $B-7I$ is diagonalizable if and only if $B$ is diagonalizable, but because $B - 7I$ has zero as an eigenvalue, the characteristic polynomial will necessarily have a zero constant term, making it much easier to factor than the polynomial you would get through straightforward calculation. We calculate

$$

\det((B - 7I) - \lambda I) = -\lambda^3 - 18 \lambda^2 - 36\lambda = -\lambda(\lambda + 6)^2,

$$

which allows you to deduce that the remaining eigenvalue of $B - 7I$ is $-6$ with algebraic multiplicity $2$. Compare to the computation

$$

\det(B - \lambda I) = -\lambda^3 + 9 \lambda^2 - 15\lambda + 7,

$$

which we can deduce has $(\lambda - 7)$ as a factor from the fact that $7$ is an eigenvalue of $B$.

A faster (but more advanced and less generalizable) way to make use of the information that $(1,1,1)$ is an eigenvector with associated eigenvalue $7$ is to consider the eigenvalues of $B^T$. If $B$ has an eigenvalue not equal to $7$ that has a two-dimensional associated eigenspace, then it would follows that the associated eigenspace is $(1,1,1)^\perp$. We can confirm that this is indeed the case by calculating $B^Tv$ for $v = (1,-1,0),(1,0,-1)$ since these vectors form a basis of $(1,1,1)^\perp$. Indeed,

$$

B^T \pmatrix{1\\-1\\0} = \pmatrix{1\\-1\\0}, \quad B^T \pmatrix{1\\0\\-1} = \pmatrix{1\\0\\-1}.

$$

In this way, we have verified that there is another eigenvalue with geometric multiplicity 2 without first calculating that eigenvalue!

For the non-diagonalizable matrix $C = [T_3]_{\mathcal B}$, there's no great way to see that it won't be diagonalizable. We can speed up the process of finding the characteristic polynomial, however, by noticing that just like last time, our matrix has $(1,1,1)$ as an eigenvector, associated this time with the eigenvalue $1$. We can then calculate $\det((B - I) - \lambda I)$, which is easier to factor because of its zero constant term.

We see that $B - I$ has $3$ as an eigenvalue (corresponding to the eigenvalue $4$ of $B$) with algebraic multiplicity $2$. Notice that $B - 4I = (B - I) - 3I$ is not a rank-1 matrix, which means that the geometric multiplicity of the eigenvalue is $1$, which means that the matrix is not diagonalizable.