Synthetic Differential Geometry by Kock opens with the following:

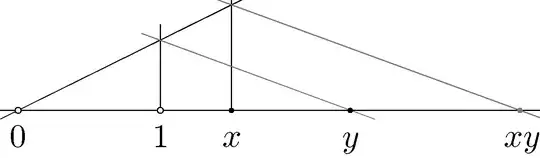

The geometric line can, as soon as one chooses two distinct points on it, be made into a commutative ring, with the two points as respectively 0 and 1. This is a decisive structure on it, already known and considered by Euclid, who assumes that his reader is able to move line segments around in the plane (which gives addition), and who teaches his reader how he, with ruler and compass, can construct the fourth proportional of three line segments; taking one of these to be [0, 1], this defines the product of the two others, and thus the multiplication on the line...Of course, this basic structure does not depend on having the (arithmetically constructed) real numbers $\mathbb{R}$ as a mathematical model for [it]).

I am confused about what exactly this ring structure is? Am I to understand that the elements of this Ring are not points on the line but line segements? Does one add two line segements by just adding their length? I looked up how to construct the fourth proportional of three line segments which is multiplication in this ring, leading me to suspect that perhaps he's referring to the ring of geometrically constructible numbers?