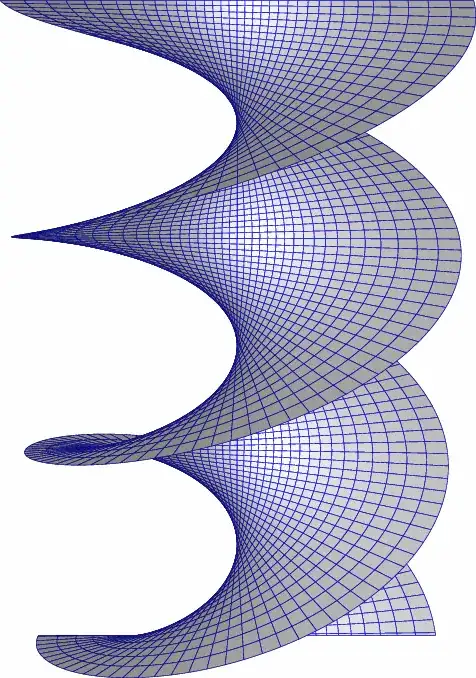

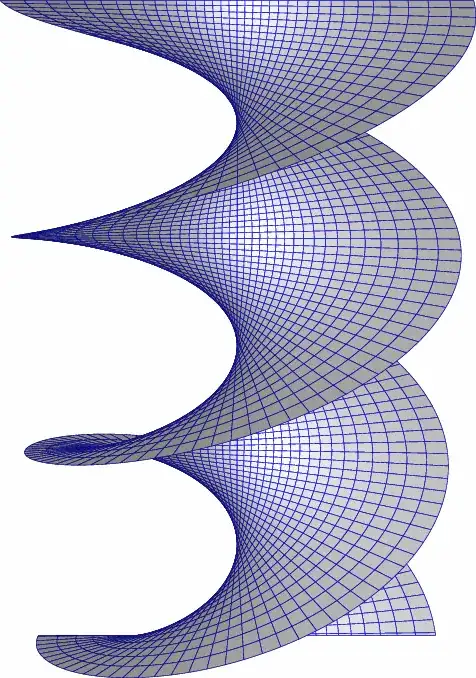

$\newcommand{\mapx}{\mathbf{x}}$tl; dr: Gliding a helicoid along itself looks like this:

In plane Euclidean geometry, there are isometries called glide reflections consisting of translation along a line followed by reflection across that line. (These operations of translation and reflection commute, i.e., can be performed in either order with identical effect.) The name "glide reflection" is standard, but this transformation is unrelated to helicoids.

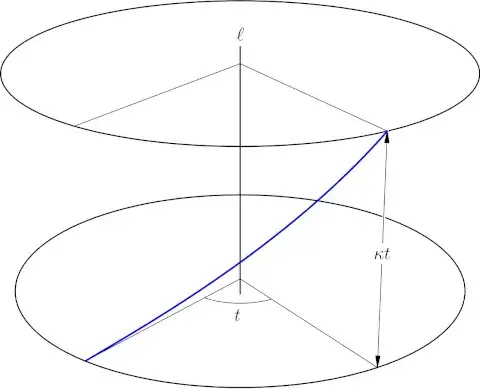

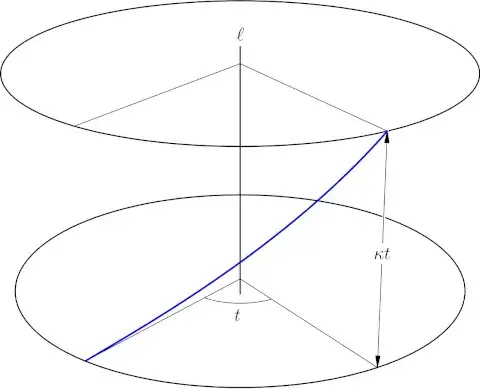

In Euclidean three-space, there exist "one-parameter groups" of isometries comprising simultaneous rotation at constant angular speed about a line $\ell$ (the axis) and translation at constant speed along $\ell$. Classically these are sometimes called screw motions after the simple machine, but at least since the 1960s that phrase has had rude associations in American English. These isometries might also be called helical motions or glide rotations, but I am not aware of either term being standard.

The translation speed divided by the angular speed is known as the pitch. Particularly, a helical motion of pitch zero is a rotation, and a translation may be viewed as a helical motion of infinite pitch.

A concrete way to interpret the phrase one-parameter group is, if we fix a line $\ell$ and a pitch $\kappa$, then the set of helical motions with axis $\ell$ and pitch $\kappa$ is a group under mapping composition.

In Cartesian coordinates $(x, y, z)$, the group of helical motions with pitch $\kappa$ about the $z$-axis may be written

$$

G_{\kappa}(t)(x, y, z) = (x\cos t - y\sin t, x\sin t + y\cos t, z + \kappa t).

$$

<>

If $C$ is a smooth curve lying in a plane perpendicular to $\ell$, then $C$ sweeps a smooth surface under any group of helical motions with axis $\ell$ and non-zero pitch. Such a surface is known as a generalized helicoid, and $C$ is a generating curve. In a sense described below, every generalized helicoid can "slide along itself."

Without further context, the helicoid refers to a surface swept by a line perpendicular to an axis under a group of helical motions of pitch $1$. Relative to the group described above, the $x$-axis sweeps a surface parametrized by either of

$$

\mapx(u, v) = (u\cos v, u\sin v, v)

$$

(generating curve parametrized at unit speed) or

$$

\mapx(u, v) = (\sinh u\cos v, \sinh u\sin v, v)

$$

(conformal parametrization), among infinitely many other possibilities.

Without further context, Steinhaus may have meant multiple things by The helicoid is the only non-rotary surface which can glide along itself, including

- "The helicoid" refers to arbitrary helicoidal surfaces.

- There is some geometric hypothesis in play, unstated in the quote, that uniquely selects the "standard" helicoid.

(If $C$ is an arbitrary curve, we may sweep $C$ by a group of helical motions, and "most of the time" get a smooth surface as a result. Different authors might call $C$ a generator even if $C$ does not lie in a plane orthogonal to the axis of helical motion.)

<>

For definiteness, assume $\bigl(x(u), y(u), 0\bigr)$ parametrizes a smooth plane curve $C$. Under the group of helical motions above, $C$ sweeps a surface parametrized by

$$

\mapx(u, v) = \bigl(x(u)\cos v - y(u)\sin v, x(u)\sin v + y(u)\cos v, \kappa v\bigr).

$$

This surface "glides along itself" in the sense that rotating about the $z$-axis through angle $t$ and translating along the $z$-axis by $\kappa t$ maps the surface to itself for every real angle $t$. More specifically,

$$

G_{\kappa}(t)\bigl(\mapx(u, v)\bigr) = \mapx(u, v + t).

$$

In words, translating the parameter $v$ by $t$ has identical effect on the parametrization as glide-rotating the image through angle $t$ with pitch $\kappa$. This formula amounts to the sum formulas for $\cos$ and $\sin$.

In fancy language, this helicoidal parametrization is equivariant relative to translation in $v$ and glide rotation of three-space.