I am looking for a function over the real line, $g$, with $g*g = g^2$ (or a proof that such a function doesn't exist on some space like $L_1 \cap L_2$ or $L_1 \cap L_\infty$). This relation can't hold in a non-trivial way over any finite space, by that I mean that if $f$ is a probability density function, then $fg^2 = fg * fg$ implies by integration that $E_f[g^2] = E_f[g]^2$, so $g$ would have to have $0$ variance. Furthermore, this relation can't hold on the positive real line since $e^{-x}$ is a probability distribution with $e^{-x}(g*g) = (e^{-x}g)* (e^{-x}g)$, which would again mean that $g$ has $0$ variance, forcing it to be zero. Alternatively, one could hope for a power series for $g$ and use the fact that $h_n \equiv x^{n-1}/(n-1)!$ has $h_n * h_m = h_{n+m}$ over the positive real line to derive that the power series of $g^2$ would have to be zero. None of the tricks in this paragraph seem to work over the entire real line, however.

Instead, Fourier transforming $g^2 = g*g$ reveals the same equation in Fourier space: $\hat{g}^2 = \hat{g^2} = \hat{g} * \hat{g}$. If we assume $g$ and $g^2$ have finite moments, this lets us relate them by differentiating $\hat{g}^2$ repeatedly to reveal the binomial-type formula $E_{g^2}[x^n] = \Sigma_{k = 0}^n {n \choose k}E_g[x^k]E_g[x^{n-k}]$, where $E_g[x]$ means $\int_{-\infty}^\infty dx g x$. This is quite the strange condition to me, but it doesn't seem to lead to any obvious contradictions. It says that the cumulants of $g^2$ are twice that of $g$.

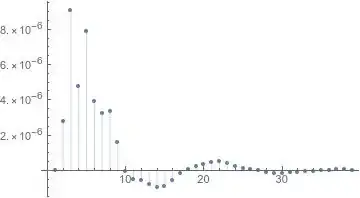

If we expand $g = \sum_{n=0} a_n \psi_n$ in terms of Hermite-Gauss functions $\psi_n(x) \equiv H_n(x)e^{-x^2/2}$ and use the convolution theorem, the fact that $F[\psi_n] = (-i)^n \psi_n$, and orthonormality of the $\psi_n$, we can derive the fact that the 4 mod 4 families of modes $\{\psi_n:n = k \hspace{.2cm}\text{mod} 4\}$ in $g^2$ result from the products over modes in $g$ whose index sums to $k \hspace{.1cm} \text{mod} 4$: $\langle \psi_k , g^2\rangle = \sum_{n+m = k\text{mod 4}} a_n a_m <\psi_n \psi_m , \psi_k> $ for any $k$. This is opposed to the usual situation where $n+m = k+2$ modes are also included in the sum. This says that the index of $g$'s modes don't mix mod 4 after squaring. This condition is difficult to work with because there is not a nice way of dealing with $<\psi_n \psi_m, \psi_k>$. If there was an extra $e^{x^2/2}$ inside that inner product, it would let us use the tripple product formula for $H_n(x)$ which has a nice form where only finitely many terms pop out (unlike the seemingly all-to-all coupling of the $\psi$ product).

A solution of $g^2 = g*g$ would lead to solutions of $g^2 = \lambda g*g$ for any $\lambda$ by using $g(x/\lambda)*g(x/\lambda) (\lambda x) = \lambda g*g(x)$. Furthermore, using $(e^{\lambda x}g)^2 = e^{2 \lambda x} g*g = e^{\lambda x} (e^{\lambda x}g)*(e^{\lambda x})$ would give us a solution to $g^2 = e^{\lambda x} g*g$ for any $\lambda$. Substituting $g(x) \rightarrow g(x+\delta)$ gives us solutions to translated equations $g^2(x) = g*g (x+\delta)$. Unfortunately, none of these transformations have made the solution to the problem obvious.

The problem becomes trivial if we are allowed to rescale like $g(x)^2 = g*g(\sqrt{2} x) \sqrt{2}$, as its just a Gaussian! Herein lies the reason why I suspect that there is no solution to $g^2 = g*g$. The left-hand side tightens $g$, whereas the right-hand side spreads $g$ out. Interestingly enough, there are solutions to $g = g*g$ (sinc) as well as $g^{1/2} = g*g$ (again Gaussian), but the homogeneous version of the problem seems more elusive. I have read some papers about solving convolutional equations, but they as far as I have seen have either been over a finite space or have not had the non-linearity present here.

I have also tried taking a fractional Fourier transform with angle $-\pi/4$ to convert $g^2 = g*g$ into $g_{-\pi/4}*_{-\pi/4}g_{-\pi/4} = g_{-\pi/4}*_{\pi/4} g_{-\pi/4}$, which leads to another two dimensional integral which is easy to write down but not solve. I thought of doing a fractional Fourier transform about a very small angle in order to make the convolution $g*g$ less delocalized as well as the product $g*g$ smoother. This didn't really lead to anything helpful.

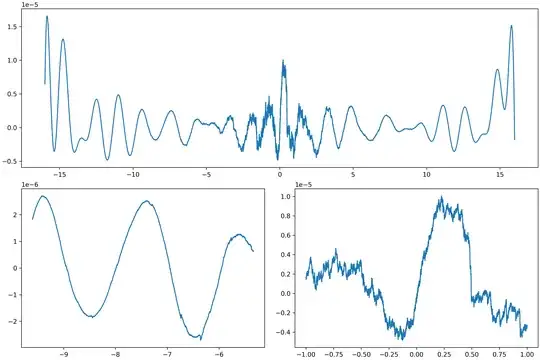

I tried thinking up of a scheme to find better and better approximations for $g$, as I would be happy even with an implicit answer or a numerical method to plot $g$. The obvious candidate $g = \sqrt{g*g}$ has the problem of there being cycles (Gaussians) as well as convolutions being difficult to compute over the whole real line. If one thinks of $g^2-g*g$ as a Lagrangian and tries to do a path integral of $e^{-|g^2-g*g|}$ over configurations of $g$ with some given $||g||$, then I think this corresponds to a badly non-local field theory. Yikes!

As a final note, the problem can be restated as finding a function where the act of squaring commutes with taking a Fourier transform: $\hat{g}^2 = \hat{g^2}$. This would be solved (sufficient but not necessary) by a function who is its own Fourier transform $g = \hat{g}$, and whose square is its own Fourier transform $g^2 = \hat{g^2}$. But again we run into the problem where there is no good basis in which to to do both the product and the Fourier transform. Polynomials multiply well but Fourier transform/convolve poorly, vice versa for Hermite Gaussians (etc etc with seemingly every choice of basis). Any help approaching this problem would be greatly appreciated, as I am seriously losing my mind over it!

Edit: There is also a simple asymptotic argument which shows that if g is upper and lower bounded by ~$x^{-n}$ at infinity for some n then it can't solve $g^2 = g*g$. The reason is that the limit of $x^n g^2$ is $0$, but the limit of $x^n g*g$ would be $\int_{-\infty}^\infty dx g(x)$, so this would have to be zero (forcing the integral of $g^2$ to be zero as well). However such an argument fails if $g$ decays faster than any polynomial, or if it repeatedly crosses $0$ as $x$ goes off to infinity.

Another edit: I believe that the answer is yes and unique (but trivial) for g taken to be a discrete vector with elements over $Z$. This is because Fourier transforming the problem moves back to a compact space where the variance argument shows that the only solution is constant, meaning that the only solution for such a $g$ is $g_i = \delta_i$.

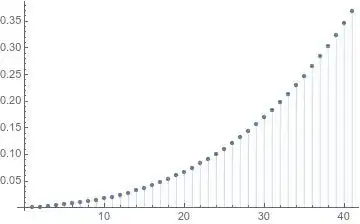

Here, one successful attempt was an expansion of the form $f(x) = ∑{n∈ℤ}a_n e^{-\frac{1}{2}c_n x^2}$. The convolution behaves nicely: $e^{-\frac{1}{2}a x^2}*e^{-\frac{1}{2} b x^2} \propto e^{-\frac{1}{2}\frac{ab}{a+b}x^2} = e^{-\frac{1}{2}(a∥b)x^2}$, using the [parallel operator](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parallel(operator)) (see also: https://math.stackexchange.com/q/1785715/99220). If one finds a nice discrete set that is closed under ∥, one could try this expansion.

– Hyperplane Oct 04 '23 at 09:47