I have wrote a Python program to plot all prime numbers up to a given limit in polar plot, that is, every point $(r, \theta)$ visible corresponds to a prime number $p$, where $r = p$, the distance from the origin, and $\theta = p$, the angle from $x$ axis counterclockwise, measured in radians.

You can see my code here, I have implemented a version of Sieve of Eratosthenes with rudimentary Wheel factorization using NumPy, to generate the primes, and I plotted them using Matplotlib. Because I am a programming enthusiast I used powers of 2 instead of powers of 10 as the limits, I generated 12 images for primes under $2^p$ where $p \in [6, 17] \cap \mathbb{Z}$, and I noticed something interesting.

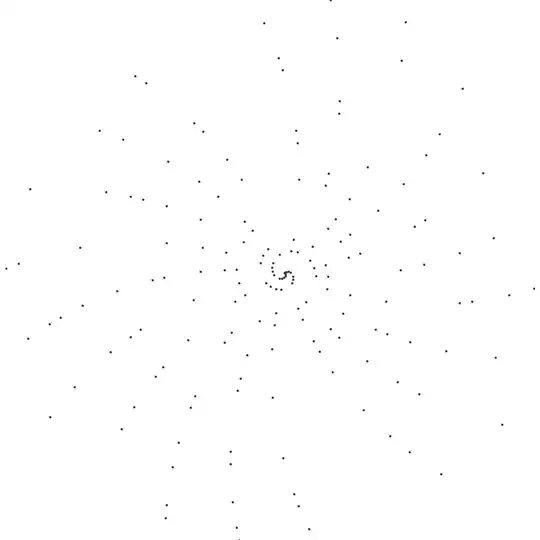

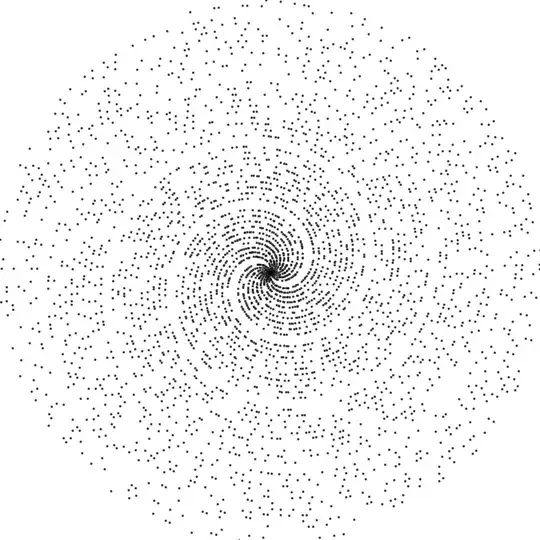

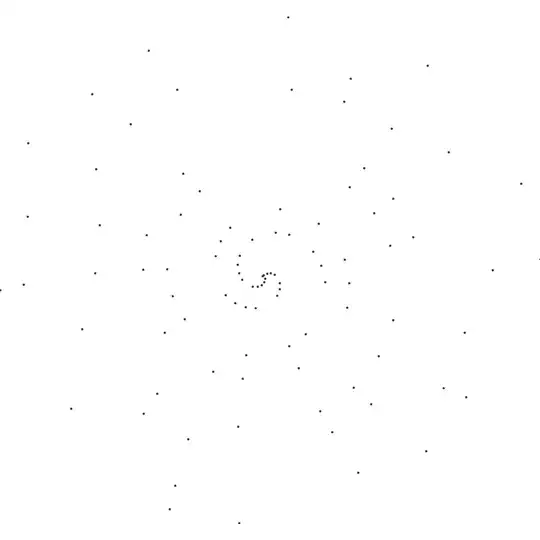

For primes under 256, the points fall on 2 spirals:

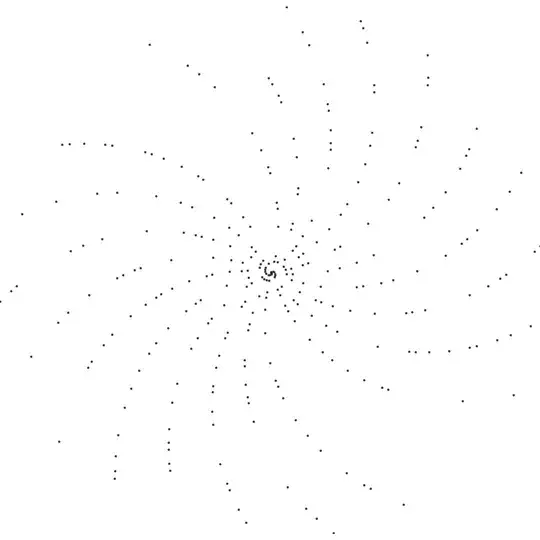

For primes under 512, the points also fall on 2 spirals, but 2 groups of 10 spirals can be spotted, and they are more ray-like than the 2 spirals, and there are 2 large gaps between the groups:

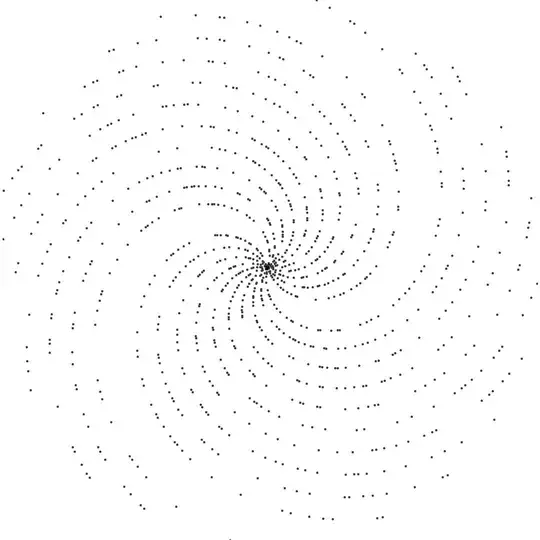

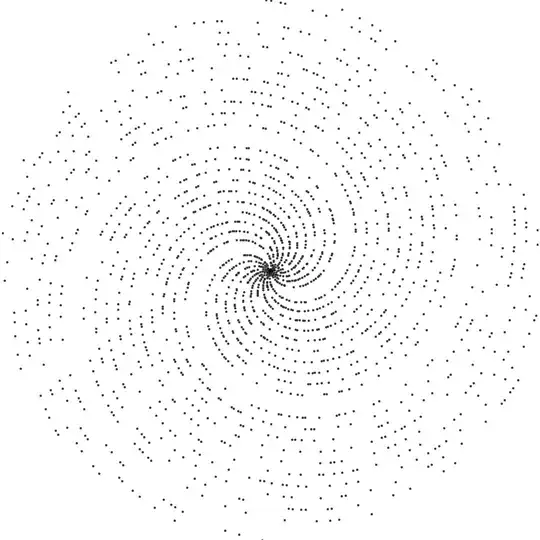

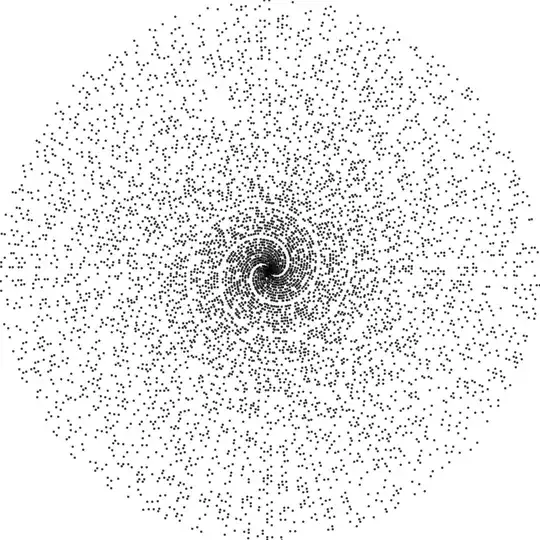

For primes under 1024 to 32768, the structure persists, the points fall on 20 spirals, grouped into 2 groups of 10, with 2 gaps that became progressively thinner:

For primes under 1024 to 32768, the structure persists, the points fall on 20 spirals, grouped into 2 groups of 10, with 2 gaps that became progressively thinner:

1024

2048

4096

8192

16384

32768

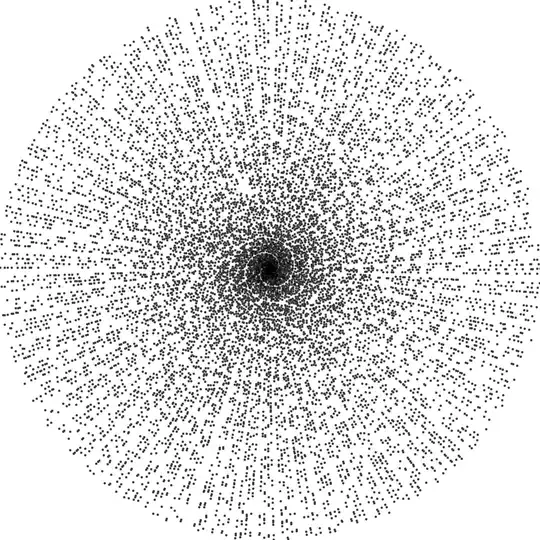

Then, the image becomes less spiral-like, the gap seems to disappear, and the points are more concentrated, and rays are formed. In the final image I made, for primes under 131072, the rays are grouped into groups of 4.

65536

131072

I know for all prime numbers $p$, $p\mod 6 \in \{1, 5\}$ must be true, except 2 and 3, because there are only 6 possibilities: $\{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}$, if the remainder is $\{0, 2, 4\}$ then it is a multiple of 2 (that is not 2), therefore composite, and if the remainder is 3 then the number is an odd multiple of 3 (that is not 3), because $6 = 2 \cdot 3$.

And I am also very familiar with modular arithmetic, and I know it is just rotation disguised. In a circle, there are $\tau$ radians, and if you rotate multiples of $\tau$ you get back at where you started, because there are only $\tau$ radians and every number must be mapped to $[0, \tau)$, so the angle is determined only by $\theta \mod \tau$ and angles $\tau$ radians apart lie on the same central ray, and angles with differences close to $\tau$ lie on close rays with a small offset.

So I suspect there are 2 groups because they are for 2 modular 6 groups, $1 (\mod 6)$ and $5 (\mod 6)$, though I am not a mathematician and I don't have any proof, nor have I thought about it thoroughly.

But the spirals are extremely likely to be caused by modular groups, the points on the same spiral have the same remainder modulo a certain number, and the small differences between the rays add up, forming spirals, though again I am not a mathematician.

I have read this question and its answer, and I know I am on the right track.

I want to color the points such that all points on the same spiral share the same color and all spirals in the same group have different colors.

My question is, how can I programmatically determine the most appropriate approximation of $\tau$ at the current scale, the number of spirals at the current scale, and which prime is on which spiral, using mathematics?