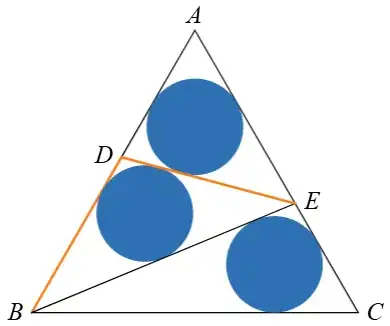

I uh, wasted so much time on this. I have no idea if there is a shorter solution, all data pieces are seemingly used by the time we get to $\left ( 2 \right )$.

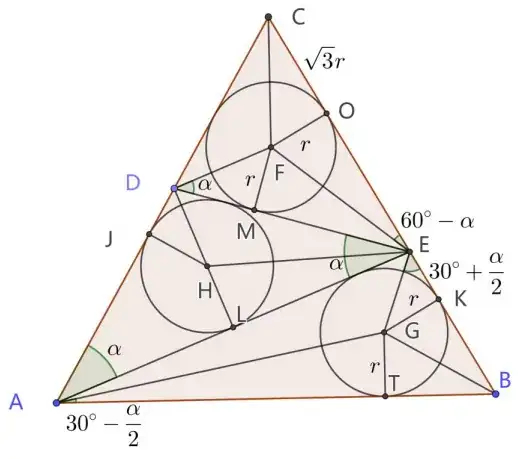

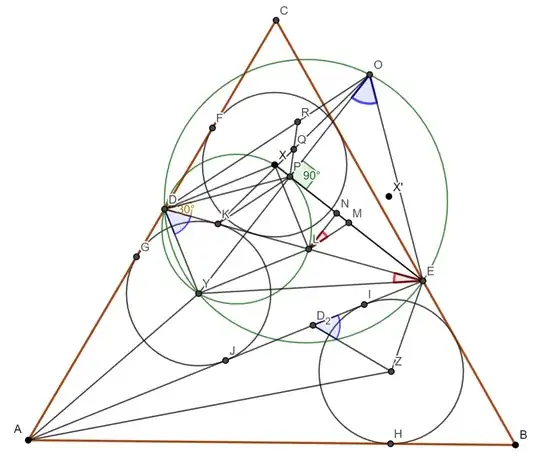

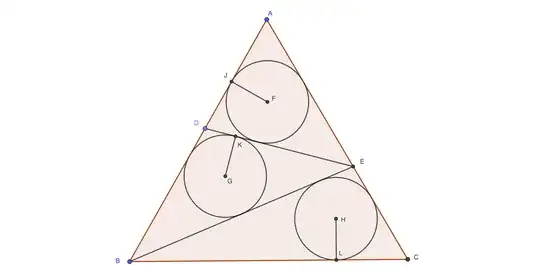

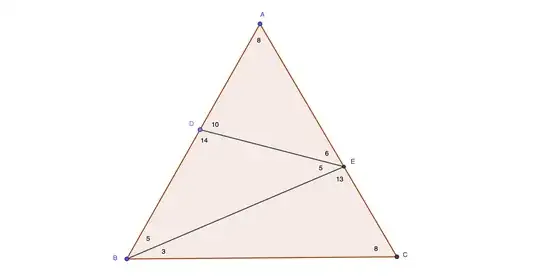

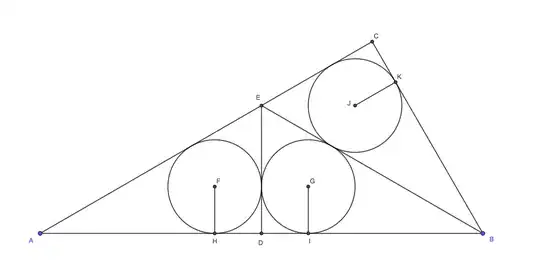

I'm not defining every point, refer to the figure. Circles $X$,$Y$, and $Z$ just refer to the circles which have those points as their center.

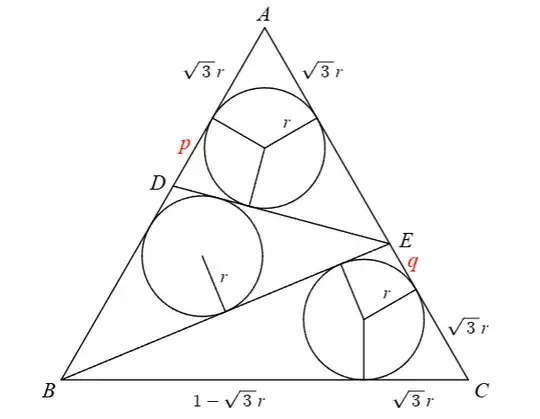

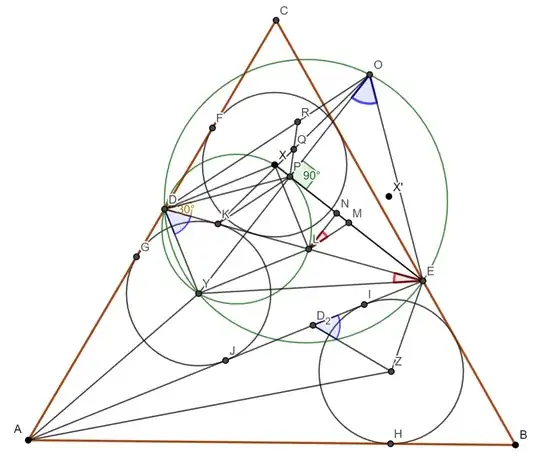

Rotate $\triangle YDX$ $180^{\circ}$ around the midpoint of $XY$ to get $\triangle XLD$. Clearly the midpoint of $XY$ lies on $DE$ because circles $X$ and $Y$ have the same radius and are both tangent to $DE$. Furthermore we have $YDX=90^{\circ}$ since $DY$ bisects $\angle ADE$ and $DX$ bisects $\angle EDC$. This implies $YDXL$ is a rectangle, so $DL=YX$. $YGFX$ is also a rectangle so $YX=GF$.

Since $\angle ACB =\angle CBA$ and circles $X$ and $Z$ have equal radius, $CF=BH$. Then $AC=AB \implies AF=AH$ and $AH=AI$, since both segments are tangent to circle $Z$ passing through $A$. This implies $GF=JI$ and $DL=JI$. We have $EJ=EK \implies DL+IE=KL+LE \implies DK+IE=LE$. Let $D_2$ lie between $IJ$ with $D_2I=DX$.

You can show that for any triangle $\triangle ABC$, $2 \cdot \angle BIC=180^{\circ}+\angle BAC$, where $I$ is the incenter of $\triangle ABC$. Call this Lemma 1. This means $\angle DXE=120^{\circ}$, so $\angle LXE=30^{\circ}$.

$IZ=KY \implies DY=D_2Z$ and $XL=D_2Z$. Let $X'$ form a parallelogram $XLEX'$. we have $X'EL=XLD=YDL$, $X'E=XL=DY=D_2Z$, and $LE=D_2E$, which means $LEX' \cong ED_2Z$. This means $LX'=EZ$, and since $XLEX'$ is a parallelogram, the midpoint $M$ of $LX'$ lies on $EX$ and we will have $LM=\frac{EZ}{2}$ and $\angle ELM=\angle IEZ$.

$\angle MLX=180^{\circ}-\angle XLD-\angle ELM=180^{\circ}-\angle YDL-\angle IEZ=180^{\circ}-(\angle XCE+\angle CEX)-\angle IEZ=90^{\circ}-30^{\circ}+(90^{\circ}-\angle CEX-\angle IEZ)=60^{\circ}+\angle KEY$

(We have three pairs of equal angles around $E$, so the sum of one from each pair will be $90^{\circ}$). Now drop a perpendicular from $L$ onto $XE$ and label the intersection $N$. $\angle LXE=30^{\circ} \implies \angle NLX=60^{\circ}$, $NL=\frac{XL}{2}$, and $\angle MLN=\angle KEY$. This means $\triangle MLN \sim \triangle YEK$, and we have $\frac{NL}{LM}=\frac{KE}{EY} \implies \frac{\frac{DY}{2}}{\frac{EZ}{2}}=\frac{KE}{EY} \implies \frac{DY}{EZ}=\frac{KE}{EY} \left ( 2 \right )$.

Construct $O$: $\triangle YEO \sim \triangle EZD_2$. Then from $\left ( 2 \right )$, $\frac{OE}{EY}=\frac{D_2Z}{EZ}=\frac{KE}{EY} \implies OE=KE$. $\angle OEY=\angle EZD_2=\angle MLX=60^{\circ}+\angle KEY \implies OEK=60^{\circ}$. Note that also $\angle YOE=\angle YDE$, so $YDOE$ is cyclic.

The next construction is not very instructive or enlightening but works regardless. Just a lot of trial and error.

Let $P$ be the foot of the perpendicular from $E$ onto $YO$. We already established $\angle XEY+\angle IEZ=90^{\circ}$, so $P$ lies on $EX$. This gives $\angle XPY=90^{\circ} \implies YDXPL$ is cyclic $\implies \angle DPY=\angle DLY$. Using Lemma 1, $\angle AYE=90^{\circ}+\angle YDE \implies \angle DPY+\angle AYE=180^{\circ} \implies \angle OPD=\angle AYE$. Combined with the fact that $\angle DOY=\angle DEY$ as $YDOE$ is cyclic, $\triangle DPO \sim \triangle AYE$ (Incidentally, $\triangle DKO \sim \triangle EZA$). We also get $\angle LDP=\angle LXP = 30^{\circ}$.

Next, $YKPE$ is cyclic since $\angle KYE=\angle YPE=90^{\circ}$ degrees, so $\angle EYP=\angle EKP$, i.e. $KP \| DO$.

We are almost done, let $Q$ be the midpoint of $KO$. $KE=OE \implies \angle EQO=90^{\circ}$ and $\angle OEQ=\frac{60^{\circ}}{2}=30^{\circ}$. This means $EPQO $ is cyclic, so $\angle OPQ=30^{\circ}$. Let $R$ be the intersection of $PQ$ with $DO$. $KP \| DO \implies QPK \sim QRO$. As $KQ=QO$ we also have $KP=RO$. This means $KROP$ is a parallelogram, so $\angle KRP=\angle RPO=30^{\circ}$, so $KDRP$ is cyclic, which means $\angle PRO=180^{\circ}-\angle DRP=\angle PKD$, which means $PRO \sim DKP$. But $KP=RO$, so $DP=PO$, so $AY=YE$ and we are done. (It means $\angle EAY=\angle YEA \implies \angle EAD=\angle DEA \implies AE=AD$)

This doesn't appear generalizable, at least with the current proof: we use $AB=AC$ right at the start, a 30-60-90 triangle to establish $\left ( 2 \right )$, not to mention $2\angle KDP=\angle OEK$.

Using $AD=DE$, it's not too bad to show that $EX=EB$, but I want to be done with this.