Edit: At the end I've added a Mathematica function that will calculate the complete distribution rather than just the mean. Depending on the options selected, one can find the "exact" distribution or the "approximately exact" distribution which depends on using machine precision numbers which results in a considerable increase in speed.

Original answer:

One can find the exact mean. Using Mathematica below is code that produces simulations from a multinomial to estimate the mean and the exact formula for the mean.

(* Generate 20 probabilities that sum to 1 *)

n = 20;

c = 1;

p = Table[i^(-c), {i, 20}];

p = p/Total[p];

(* Run simulations )

nsim = 1000000;

s[i_] := Sum[p[[j]]^i, {j, Length[p]}]

x = RandomChoice[p -> Range[Length[p]], {nsim, n + 1}];

mean = 0;

Do[k = 2;

While[Select[x[[i, 1 ;; k - 1]], # == x[[i, k]] &] == {} && k < (n + 1), k = k + 1];

mean = mean + k,

{i, nsim}]

mean = mean/nsim // N

( 4.63702 *)

(* Exact mean )

kmax = Length[p] + 1;

2 s[2] + Sum[k (k - 1) MomentConvert[AugmentedSymmetricPolynomial[Join[{2}, ConstantArray[1, k - 2]]],

"PowerSymmetricPolynomial"], {k, 3, kmax}] /.

PowerSymmetricPolynomial[i_] -> s[i] // Expand // N

( 4.63338 *)

Revised answer:

The following function can find the exact distribution of the time until the first collision or the exact probabilities for a specific number of draws until the first collision happening up to 50 draws or the approximate probabilities when using machine precision numbers.

approxExact[d_, p_, OptionsPattern[]] := Module[{s, pr, prob, total, kk},

(* Returns the probability distribution of the number of draws until the first collision *)

(* d is the number of multinomial classes *)

(* The probability of selecting class i is proportional to i^(-p) *)

(* Optional arguments: *)

(* "epsilon" Continue until the total probability of events is at least 1-epsilon *)

(* (default is 10^-8) *)

(* "precision" Numeric precision of power symmetric polynomials (default is 50) *)

(* "print" True or False to print results as one goes along (default is True) *)

(* "kmax" Maximum order of power symmetric polynomials to consider (default is 50) *)

s[k_] := N[HarmonicNumber[d, p k]/HarmonicNumber[d, p]^k, OptionValue["precision"]];

pr = ConstantArray[{0, 0}, Min[d + 1, OptionValue["kmax"]]];

pr[[All, 1]] = Range[Length[pr]];

prob = MomentConvert[AugmentedSymmetricPolynomial[{2}],

"PowerSymmetricPolynomial"] /. PowerSymmetricPolynomial[kk_] -> s[kk];

pr[[1]] = {1, 0};

pr[[2]] = {2, prob};

total = prob;

k = 2;

If[OptionValue["print"], Print[{pr[[2]], total}]];

While[total <= 1 - Rationalize[OptionValue["epsilon"], 0] &&

k < OptionValue["kmax"] && k < d + 1, k = k + 1;

pr[[k]] = {k, (k - 1) MomentConvert[AugmentedSymmetricPolynomial[ Join[{2}, ConstantArray[1, k - 2]]],

"PowerSymmetricPolynomial"] /. PowerSymmetricPolynomial[kk_] -> s[kk]};

total = total + pr[[k, 2]];

If[OptionValue["print"], Print[{pr[[k]], total}]]];

pr[[2 ;; k]]]

Options[approxExact] = {"epsilon" -> 10^-6, "kmax" -> 50, "precision" -> 50, "print" -> False};

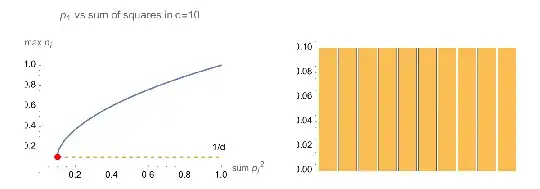

Consider $d=10$ and $p=1$:

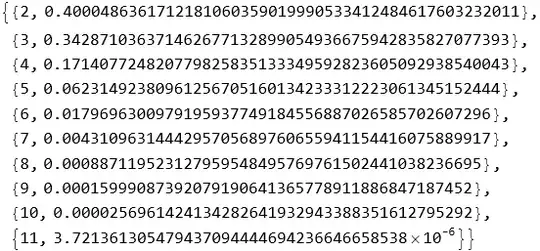

pmf1 = approxExact[10, 1]

(* {{2, 0.18064971668708334183046614833146934843581750460511},

{3, 0.2659818277978277078742270573248618320164719105871},

{4, 0.246306767894317825602528447941221519590155694619},

{5, 0.168680227553142139284552160368127823227998051874},

{6, 0.08880058815526647151857056458703230730218624454},

{7, 0.03594943992243974232191051449091169926341719537},

{8, 0.0109236474431937688476826236147190848157714520},

{9, 0.0023611030135141392096358410495732957730522974},\

{10, 0.000325160983801715352471323634201073447003952},

{11, 0.000021520549413148157955318657882016128125697}} *)

mean1 = pmf1[[All, 1]] . pmf1[[All, 2]]

(* 3.8844501770480480184116903511442503784417661 *)

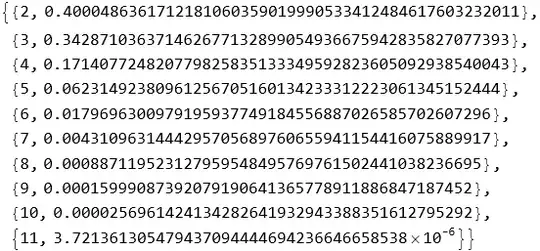

Now getting the exact values:

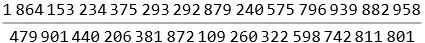

pmf2 = approxExact[10, 1, "epsilon" -> 0, "precision" -> ∞]

mean2 = pmf2[[All, 1]] . pmf2[[All, 2]]

This can even work for very large values of $d$:

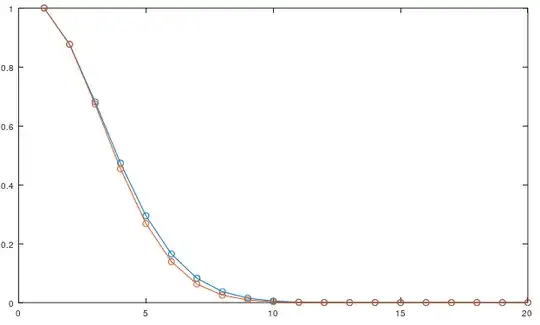

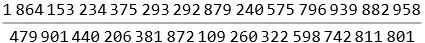

pmf3 = approxExact[10000, 2]

The covers most of the probability distribution in that the sum of the probabilities shown above is 0.999999442316189999555627433782474244630006:

Total[pmf3[[All, 2]]]

(* 0.999999442316189999555627433782474244630006 *)