$\def\FF{\mathbb{F}}$I want to make three points.

(1) The generating function for this sequence $\bmod 2$ is a rational function.

(2) There are good tools for understanding the fractal behavior of the coefficients of rational generating functions modulo $p$.

(3) These tools could, in principle, extract the box counting dimension as $\log \lambda$ where $\lambda$ is an eigenvalue of a certain stochastic matrix.

(1) The generating function for this sequence $\bmod 2$ is a rational function.

I'll write $[n]$ for $\{ 1,2,3, \ldots, n \}$.

I will analyze the behavior of the sequence where $1$-cycles DO count as increasing.

For a permutation of $n$, let us define the following statistics: Let $k_i$ be the number of increasing $i$-cycles, let $\ell$ be the number of non-increasing cycles (all of which have length $\geq 3$) and let $m$ be the number of elements in non-increasing cycles.

So $n = \sum i k_i + m$.

Given a permutation of $[n]$, there are $n+1$ ways that we can turn it into a permutation of $[n+1]$ by inserting $n+1$ into a cycle. For example, given the permutation $(12)$ of $[2]$, we could turn it into $(132)$, $(123)$ or $(12)(3)$; the first two involve inserting $3$ into the cycle $(12)$, and the last involves making a new $1$-cycle for $3$. Let's see how these affect our statistics.

(a) There are $k_i$ ways that we can insert $n+1$ into an increasing $i$-cycle and keep it increasing. In this case, $k_i$ changes to $k_i -1$ and $k_{i+1}$ changes to $k_{i+1}+1$.

(b) There are $(i-1) k_i$ ways that we can insert $n+1$ into an increasing $i$-cycle and make it non-increasing. In this case, $k_i$ changes to $k_i -1$, $\ell$ changes to $\ell+1$ and $m$ changes to $m+i+1$.

(c) There are $m$ ways that we can insert $n+1$ into a non-increasing cycle. In this case, $m$ changes to $m+1$.

(d) There is $1$ way that we can make $n+1$ into a $1$-cycle. In this case, $k_1$ changes to $k_1+1$.

Things get simpler when we only need to count the number of transitions modulo $2$. Put $p = \sum_{i \equiv 1 \bmod 2} k_i$ and $q = \sum_{i \equiv 0 \bmod 2} k_i$.

We remark that $n \equiv p+m \bmod 2$.

Here are the new cases:

(a1) There are $p$ ways that we can insert $n+1$ into an increasing odd cycle and keep it increasing. In this case, $(p,q,m)$ changes to $(p - 1, q + 1, m)$.

(a2) There are $q$ ways that we can insert $n+1$ into an increasing even cycle and keep it increasing. In this case, $(p,q,m)$ changes to $(p + 1, q - 1, m)$.

(b1) There are $0 \bmod 2$ ways that we can insert $n+1$ into an odd increasing cycle and make it non-increasing. Since there are $0 \bmod 2$ ways to do this, we don't have to think about it.

(b2) There are $q \bmod 2$ ways that we can insert $n+1$ into an even increasing cycle and make it non-increasing. In this case, $(p,q,m) \bmod 2$ changes to $(p, q-1, m+1) \bmod 2$ and $\ell$ changes to $\ell+1$.

(c) There are $m$ ways that we can insert $n+1$ into a non-increasing cycle. In this case, $(p,q,m)$ changes to $(p, q, m+1)$.

(d) There is $1$ way that we can make $n+1$ into a $1$-cycle. In this case, $(p,q,m)$ changes to $(p+1, q,m)$.

In some cases, we understand exactly how $(p,q,\ell, m)$ change but, in other cases, we only understand how they change modulo $2$.

Let's only ever keep track of $(p, q, m)$ modulo $2$. In this case, our six cases collapse back to four, since $(p-1,q+1,m) \equiv (p+1,q-1,m) \bmod 2$ and we can forget about $(b1)$ completely:

(a) There are $p+q \bmod 2$ ways to insert $n+1$ into an increasing cycle and keep it increasing. In this case, $(p,q,m) \bmod 2$ changes to $(p+1, q+1, m) \bmod 2$.

(b) There are $q \bmod 2$ ways to insert $n+1$ into an even increasing cycle and make in non-increasing. In this case, $(p,q,m) \bmod 2$ changes to $(p, q+1, m+1) \bmod 2$ and $\ell$ changes to $\ell+1$.

(c) There are $m \bmod 2$ ways that we can insert $n+1$ into a non-increasing cycle. In this case, $(p,q,m) \bmod 2$ changes to $(p, q, m+1) \bmod 2$.

(d) There is $1 \bmod 2$ way that we can make $n+1$ into a $1$-cycle. In this case, $(p,q,m) \bmod 2$ changes to $(p+1, q,m) \bmod 2$.

Let $A_{000}(z,t)$ be the generating function for permutations with $(p,q,m) \equiv (0,0,0) \bmod 2$, weighted by $z^{\ell} t^n$, and counted modulo $2$. We define $A_{001}$, $A_{010}$, ..., $A_{111}$ similarly. Then we have eight linear equations:

$$

\begin{array}{ccccccccccc}

A_{000} &=& && zt A_{011} &+& t A_{001} &+& t A_{100} &+& 1 \\

A_{001} &=& && zt A_{010} && &+& t A_{101} && \\

A_{010} &=& t A_{100} && &+& t A_{011} &+& t A_{110} && \\

A_{011} &=& t A_{101} && &+& &+& t A_{111} && \\

A_{100} &=& t A_{010} &+& zt A_{111} &+& t A_{101} &+& t A_{000} && \\

A_{101} &=& t A_{011} &+& zt A_{110} && &+& t A_{001} && \\

A_{110} &=& && &+& t A_{111} &+& t A_{010} && \\

A_{111} &=& && &+& &+& t A_{011}. && \\

\end{array}$$

The first column describes the effect of case (a), the second column describes the effect of case (b), etcetera.

For example, the $zt A_{011}$ term in the first row, second column, indicates that, if $(p,q,m) \equiv (0,1,1) \bmod 2$, then case (b) can occur in $q \equiv 1 \bmod 2$ ways, and the weight $z^{\ell} t^n$ will change to $z^{\ell+1} t^{n+1}$.

The $+1$ in the first row is the empty permutation of the empty set.

Eight linear equations in eight variables is a mess for a human, but no problem for a computer.

I was just double checking my work and preparing to enter it into Mathematica, when I discovered that I was treating $1$-cycles differently from the OEIS (better, IMNSHO).

Fixing this issue gives $16$ linear equations in $16$ variables, so I decided to stop. (Also, you get negative powers of $z$, because inserting $n+1$ into a $1$-cycle changes $\ell$ to $\ell-1$, since the $1$-cycle is considered non-increasing but the resulting $2$-cycle is considered increasing.)

But, in any case, it is clear that each of the $A_{ijk}$'s, and therefore their sum, will be a rational function, in $\FF_2(z,t)$.

And this gives us a lot of tools to use.

(2) There are good tools for understanding the fractal behavior of the coefficients of rational generating functions modulo $p$.

Suppose we have a rational function $F(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_d) = \frac{P(x_1, \ldots, x_d)}{Q(x_1, \ldots, x_d)}$ with coefficients in $\FF_p$.

Expand $F$ as a power series $\sum_{e_1, e_2, \ldots, e_d} F_{e_1, e_2, \ldots, e_d} x_1^{e_1} \cdots x_d^{e_d}$. How can we compute the coefficients $F_{e_1, e_2, \ldots, e_d} x_1^{e_1} \cdots x_d^{e_d}$ in terms of combinatorial properties of $(e_1, e_2, \ldots, e_d$)?

A basic example is $\tfrac{1}{1-y(1+x)} = \sum_{k,n} \binom{n}{k} x^k y^n$.

Here we can use Lucas's theorem: Write $k$ and $n$ in base $p$ as $k = \sum k_i p^i$ and $n = \sum n_i p^i$, with $0 \leq k_i, n_i \leq p-1$.

Lucas's theorem tells us that $\binom{n}{k} = \prod_i \binom{n_i}{k_i} \bmod p$.

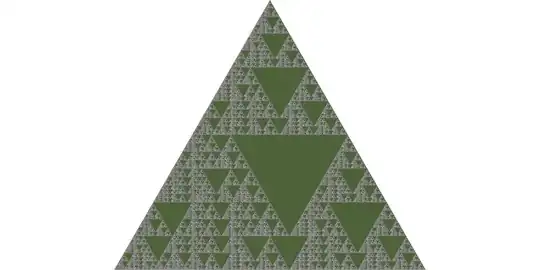

From this, it is easy to recover the standard Sierpinski gasket image of Pascal's triangle modulo $2$.

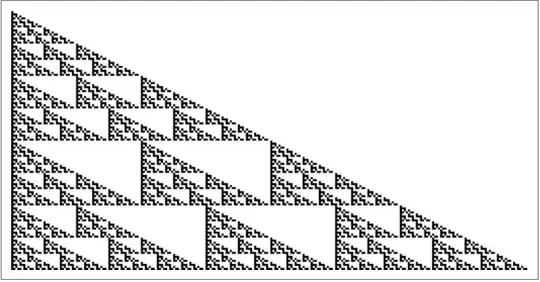

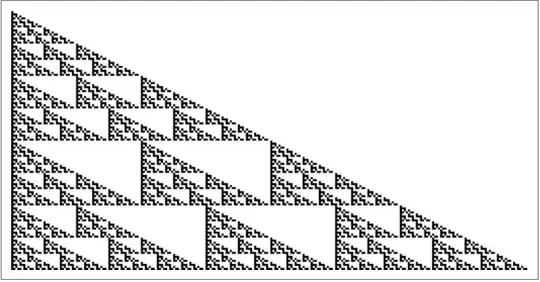

This example is pretty, but too simple to show the general case. On the other hand, the OP's example is way too big for my taste. I'm going to compromise and, as my running example, use the trinomial coefficients (OEIS A027907):

$$\frac{1}{1-y(1+x+x^2)} = \sum \binom{n}{k}_3 x^k y^n.$$

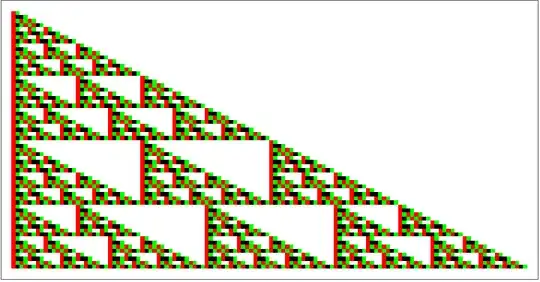

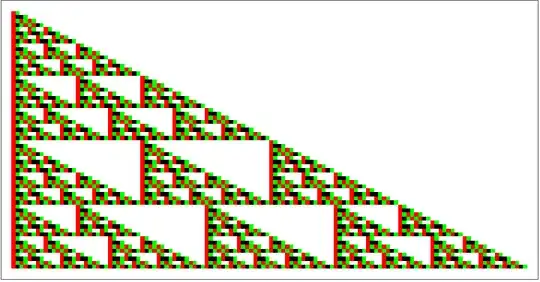

Here is a picture of the trinomial coefficients modulo $2$. (Here $0 \leq n \leq 127$ and $0 \leq k \leq 255$.)

The key tool that we are going to use is the multivariate version of Christol's theorem.

I couldn't find an online reference for the multivariate case. In print, see Chapter 14 of Allouche and Shallit, Automatic Sequences.

I'll state everything for two variable functions, although the $d$-variable case is exactly the same with more indices.

Here is the usual statement of Christol's theorem (in multiple variables):

Let $\sum F_{nk} x^k y^n$ be a formal power series with coeffcients in $\FF_p$.

Write $k$ and $n$ in base $p$ as $k = \sum k_i p^i$ and $n = \sum n_i p^i$, with $0 \leq k_i, n_i \leq p-1$.

Then the following are equivalent:

(1) There is a finite state automata (FSA) which, when fed the inputs $(n_0, k_0)$, $(n_1, k_1)$, ..., $(n_r, k_r)$, outputs $F_{nk}$.

(2) The power series $\sum F_{nk} x^k y^n$ is algebraic over $\FF_p(x,y)$.

I prefer a different formulation, which will not require you to learn what an FSA is.

Condition (1) is equivalent to:

(1') There is a positive integer $D$ for which we can find $p^2$ many $D \times D$-matrices $C(i,j)$, for $0 \leq i,j \leq p-1$, and two vectors $\vec{u}$ and $\vec{v}$, such that

$$F_{nk} = \vec{v}^T C(k_r, n_r) C(k_{r-1}, n_{r-1}) \cdots C(k_1, n_1) C(k_0, n_0) \vec{u}.$$

The entries of the matrices and the vectors are in $\FF_p$.

So, Lucas' theorem is the case where $D=1$, $C(i,j)$ is the $1 \times 1$ matrix ${\big[} \binom{j}{i} {\big]}$ and $\vec{u} = \vec{v} = [1]$.

To see the equivalence of (1) and (1'), given an FSA with $D$ states, we can make $D \times D$ matrices which encode the transitions of the FSA. We then use $\vec{u}$ to encode the initial state, and $\vec{v}$ to encode the final output.

Conversely, given $D \times D$ matrices, we can make an FSA with $p^D$ states which keeps track of the matrix product.

I like (1') better because (a) I think most people know matrices better than FSA's (b) the matrices can be much smaller than the FSA and (c) condition (1') is what shows up naturally when you do computations.

Where do conditions (1) and (1') come from?

Define $p^2$ many operators $c_{ij}$ from the vector space of formal power series to itself by the equation

$$F(x,y) = \sum_{i,j=0}^{p-1} x^i y^j c_{ij}(F)(x^p, y^p).$$

Thus, the coefficient of $x^k y^n$ in $F(x,y)$ is the coefficient of $x^0 y^0$ in

$$c(k_r, n_r) c(k_{r-1}, n_{r-1}) \cdots c(k_1, n_1) c(k_0, n_0) (F).$$

For any power series $F$, let $X$ be the set of all power series obtained by repeatedly applying the operators $c_{ij}$ to $F$ in any order, and let $V$ be the $\FF_p$-vector space spanned by $X$. Then (1) is equivalent to "$X$ is finite" and (1') is equivalent to "$V$ is finite dimensional". The states of the FSA are the elements of $X$, with the transition rules encoding how the $c_{ij}$ map $X$ to itself; the vectors in $\FF_p^D$ are the elements of $V$ (in some chosen basis) and the maps $C(i,j)$ are, again, the way that $c_{ij}$ maps $V$ to itself.

Thus, to make Christol's theorem concrete for some algebraic function $F(x,y)$, we need to find a finite dimensional vector space $V$, containing $F(x,y)$, which is mapped to itself by all the $c_{ij}$.

In order to compute $c_{ij}(F)$, you extract the coefficients of $x^n y^k$ where $(n,k) \equiv (i,j) \bmod p$.

If $F(x,y)$ is a rational function $\tfrac{P(x,y)}{Q(x,y)}$, then you can most easily do this by writing $F(x,y) = \tfrac{P(x,y) Q(x,y)^{p-1}}{Q(x^p, y^p)}$, expanding the numerator and grouping terms by the exponents modulo $p$.

Then $c_{ij}(\tfrac{P}{Q})$ will be of the form $\tfrac{R}{Q}$, where $R$ is produced by the "expand and group" procedure.

This sounds very abstract, so let's go back to our trinomial example. I'll take $V$ to be the $2$-dimensional vector space of rational functions of the form $\tfrac{a+bx}{1+y+xy+xy^2}$. We compute

$$\tfrac{a+bx}{1+y+xy+x^2y}=\tfrac{(a+bx)(1+y+xy+x^2y)}{(1+y+xy+x^2y)^2}=$$

$$\tfrac{a}{1+y^2+x^2y^2+x^4 y^2} + x \tfrac{b}{1+y^2+x^2y^2+x^4 y^2} + y \tfrac{a + a x^2 + b x^2}{1+y^2+x^2y^2+x^4 y^2} + xy \tfrac{a + b + b x^2}{1+y^2+x^2y^2+x^4 y^2}.$$

We compute that

$$c_{00}\left( \tfrac{a+bx}{1+y+xy+x^2y} \right) = \tfrac{a}{1+y+xy+x^2y} \qquad

c_{10}\left( \tfrac{a+bx}{1+y+xy+x^2y} \right) = \tfrac{b}{1+y+xy+x^2y}$$

$$c_{01}\left( \tfrac{a+bx}{1+y+xy+x^2y} \right) = \tfrac{a+(a+b)x}{1+y+xy+x^2y} \qquad

c_{11}\left( \tfrac{a+bx}{1+y+xy+x^2y} \right) = \tfrac{(a+b)+bx}{1+y+xy+x^2y} .

$$

In particular, we see that each of the $c_{ij}$ really does map the vector space of rational functions of the form $\tfrac{a+bx}{1+y+xy+xy^2}$ to itself.

In the case of a general rational function, if we want to study $\tfrac{P(x,y)}{Q(x,y)}$, we consider the vector space of rational functions of the form $\tfrac{N(x,y)}{Q(x,y)}$, where the exponents of $N(x,y)$ lie in some polytope.

Presumably, one could write down the right polytope to use in terms of the Newton polytopes of $P$ and $Q$, but I found trial and error was easier than abstract thought here.

Equation $(\ast)$ says that $c_{00}$ transforms the numerator by $(a+bx) \mapsto a$. In the basis $(1, x)$ this means that $c_{00}$ acts by the matrix $\begin{bmatrix} 1&0 \\ 0&0 \\ \end{bmatrix}$. We read off each of the matrices similarly:

$$

C(0,0) = \begin{bmatrix} 1&0 \\ 0&0 \\ \end{bmatrix} \qquad

C(1,0) = \begin{bmatrix} 0&1 \\ 0&0 \\ \end{bmatrix}$$

$$C(0,1) = \begin{bmatrix} 1&0 \\ 1&1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \qquad

C(1,1) = \begin{bmatrix} 1&1 \\ 0&1 \\ \end{bmatrix} .

$$

Now, we want to compute the coefficient of $x^0 y^0$ in $c(k_r, n_r) c(k_{r-1}, n_{r-1}) \cdots c(k_1, n_1) c(k_0, n_0) \tfrac{1}{1+y+xy + xy^2}$.

The initial power series $\tfrac{1}{1+y+xy + xy^2}$ corresponds to the column vector $\begin{bmatrix} 1\\ 0 \end{bmatrix}$.

Extracting the coefficient of $x^0 y^0$ in our basis is dot product with the row vector $\begin{bmatrix} 1&0 \end{bmatrix}$.

So we extract the "trinomial Lucas formula"

$$\binom{n}{k}_3 \equiv \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} C(k_r, n_r) C(k_{r-1}, n_{r-1}) \cdots C(k_1, n_1) C(k_0, n_0) \begin{bmatrix} 1\\0 \end{bmatrix} \bmod 2$$

(3) These tools could, in principle, extract the box counting dimension as $\log \lambda$ where $\lambda$ is an eigenvalue of a certain stochastic matrix.

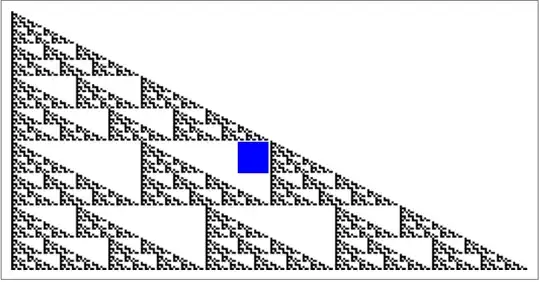

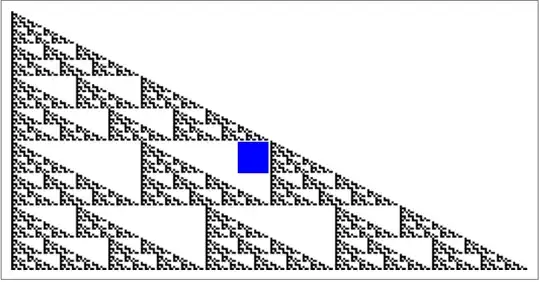

And now, the final part! Look back at that plot of the trinomial coefficients. It has some big white spaces. For example, the box shown in blue below is the region $112 \leq k \leq 127$ and $64 \leq n \leq 89$.

Or, in base $2$, it is all the numbers where $k$ starts $(0111 \cdots)_2$ and $n$ starts $(0100 \cdots)_2$.

The important thing is that this isn't just true at this particular $128 \times 256$ resolution. At any scale, for any $(k,n)$ with binary expansions starting $(0111\cdots,\ 0100\cdots)$, we will have $c(k,n)=0$.

We can see this by computing the matrix product

$$\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} C(0,0) C(1,1) C(1,0) C(1,0) \cdots =

\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1&0 \\ 0&0 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1&1 \\ 0&1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 0&1 \\ 0&0 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 0&1 \\ 0&0 \\ \end{bmatrix} \cdots = \begin{bmatrix} 0&0 \end{bmatrix}$$

regardless of what the future factors are. (There are examples that use fewer digits, but they land outside the triangle, and I thought a box in the interior would be more impressive.)

In general, if $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} C(k_r, n_r) C(k_{r-1}, n_{r-1}) \cdots C(k_q, n_q)$ is $\begin{bmatrix} 0&0 \end{bmatrix}$, we will get a white square corresponding to any $(k,n)$ whose binary expansions start $((k_r k_{r-1} \cdots k_q)_2, (n_r n_{r-1} \cdots n_q)_2)$, irrespective of how many factors come afterwards.

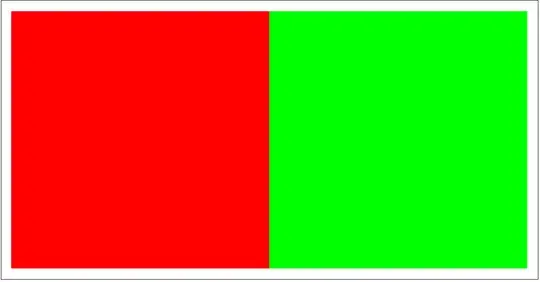

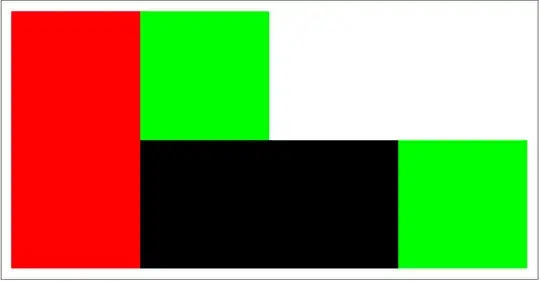

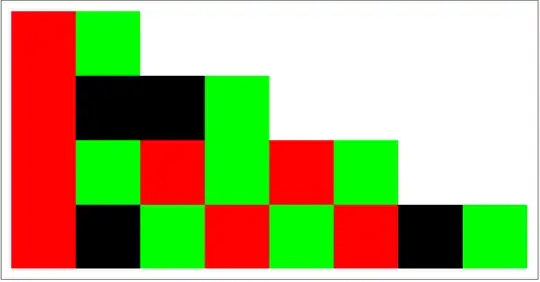

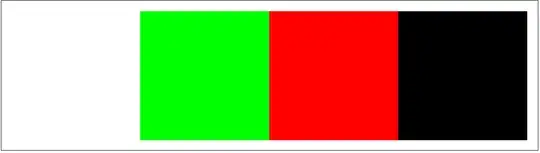

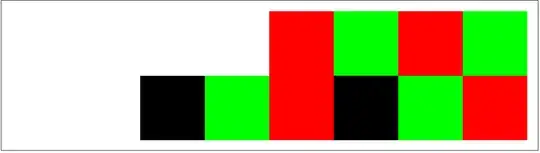

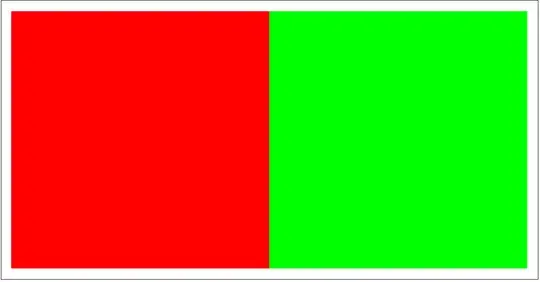

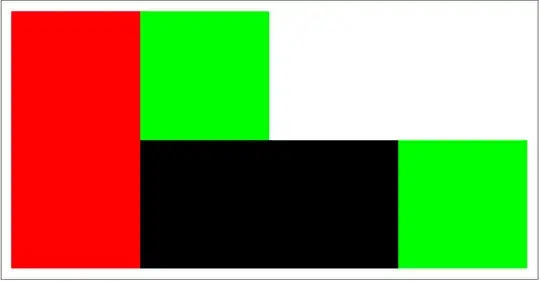

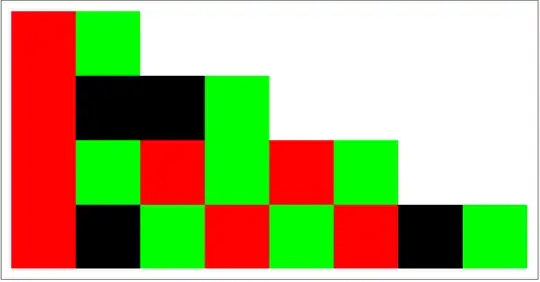

This suggests coloring the grid according to the value of the product $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} C(k_r, n_r) C(k_{r-1}, n_{r-1}) \cdots C(k_q, n_q)$. I'll use white for $\begin{bmatrix} 0&0 \end{bmatrix}$, green for $\begin{bmatrix} 0&1 \end{bmatrix}$,

red for $\begin{bmatrix} 1&0 \end{bmatrix}$ and black for $\begin{bmatrix} 1&1 \end{bmatrix}$.

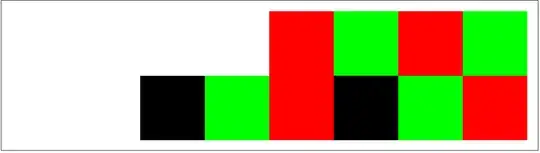

Here are the results for $r=0$, $r=1$, $r=2$ and $r=6$.

You can see the fractal form start to emerge.

In particular, note that any box which is white at a given stage remains white at all future stages.

More generally, we have the following transformation rules: Each of the four tiles in the top row, transforms into the $2 \times 2$ grid in the bottom row.

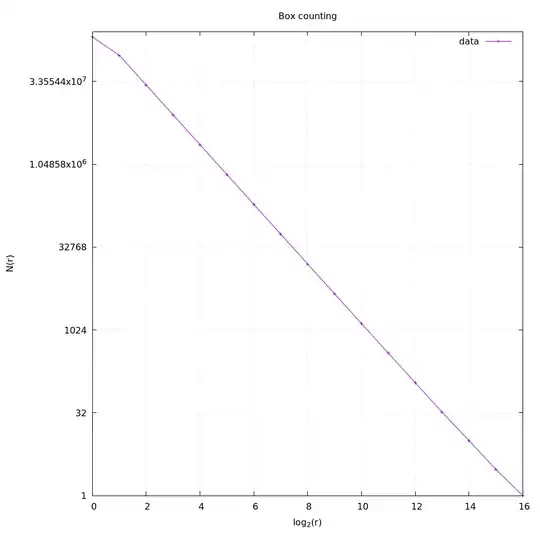

So, let's compute box counting dimension! We just need to count the number of colored (red, green or black) boxes.

Letting $w(k)$, $g(k)$, $r(k)$ and $b(k)$ be the number of white, green, red and black boxes at level $k$, we have

$$\begin{bmatrix} w(k+1) \\ g(k+1) \\ r(k+1) \\ b(k+1) \\ \end{bmatrix} =

\begin{bmatrix} 4 & 2 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 1 & 2 \\

0 & 0 & 2 & 2 \\

0 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix} w(k) \\ g(k) \\ r(k) \\ b(k) \\ \end{bmatrix}. $$

(Just count the boxes of each color in the transformation rule.)

This matrix has eigenvalues $4$, $1 \pm \sqrt{5}$ and $1$.

The eigenvector corresponding to $4$ is $[1 \ 0 \ 0 \ 0 ]^T$, indicating that, for large $k$, $w(k)$ is roughly $4^k$ (almost all the boxes are white) and the number of colored boxes are growing slower than $4^k$.

The next largest eigenvalue is $1+\sqrt{5} \approx 3.23$, with eigenvector $[(-3-\sqrt{5}) \ 2\ 2\ (-1+\sqrt{5})]^T$. So the numbers of red, green and black boxes grow like $(1+\sqrt{5})^k$ (and in the proportions $2:2:(-1+\sqrt{5})$).

The number of colored boxes is $\approx c(1+\sqrt{5})^k$ for some constant $c$, and so the box counting dimension is

$$\lim_{k \to \infty} \frac{\log (c(1+\sqrt{5})^k)}{\log 2^k} = \frac{\log( (1+\sqrt{5})}{\log 2}\approx 1.69.$$

To review: The first big section shows how to get a rational generating function in $\mathbb{F}_2(x,y)$ for the triangle you are interested in. The second section shows how to derive a Lucas like rule for the coefficients. And the third section shows you how to compute a box counting dimension. Have fun!