A harmonic function is one which solves Laplace's Equation $\Delta u=0$. The maximum principle states that over some domain $D$, $u$ achieves a maximum and minimum on $\partial D$, and nowhere inside $D$.

I am struggling to understand the proof of this principle. I am new to proofs and I would appreciate an appeal to physical intuition much more than a rigorous mathematical proof. Here are my questions:

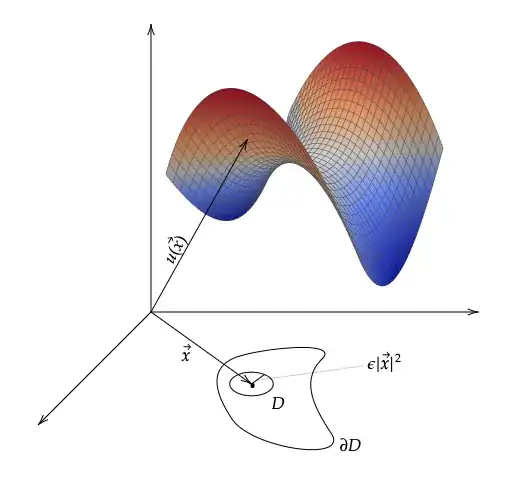

- One proof is to consider a point $v(\vec{x})=u(\vec{x})+\epsilon | \vec{x}|^2$ where $\vec{x}=(x,y)$ and $|x|=(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{\frac{1}{2}}$. Then, $\Delta v= \Delta u + \epsilon \Delta (x^2+y^2)=0+4\epsilon >0$. But a maximum has $\Delta v\leq0$, thus a contradiction. Would this be akin to the geometric interpretation shown below? If not, what would $u(\vec{x}), v(\vec{x})$, and $\epsilon|x|^2$ actually look like? In addition, $\epsilon|x|^2$ seems like a scalar, and yet we are adding it to the vector $u(\vec{x})$.

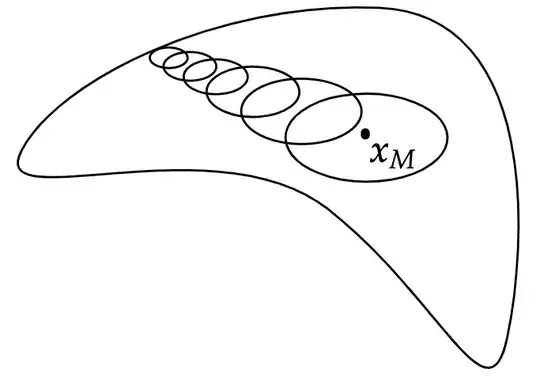

- Another proof assumes a maximum $x_M\in D$. Then all the points equidistant from $x_M$ must have an average value of $x_M$, by the mean value theorem. But if $x_M$ is the maximum, all these points $x\leq x_M$. Thus, $x=x_M$ for all $x$ on that circle. We repeat this argument, drawing more circles until we reach the boundary. But how does this prove the maximum principle? It seems to work only for circles, for one, and not an arbitrarily shaped domain. In addition, I don't quite understand how the mean value theorem implies that the average value of $x$ on the circle must be $x_M$.

Any help is much appreciated. Again, I would greatly appreciate an appeal to physical intuition as opposed to rigorous mathematics.