While reading Walter Rudin's Principles of Mathematical Analysis, I ran into the following theorem and proof:

Theorem 2.12. Let $\left\{E_n\right\}$, $n=1,2,\dots$, be a sequence of countable sets, and put

$$ S=\bigcup_{n=1}^\infty E_n. $$

Then $S$ is countable.

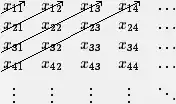

Proof. Let every set $E_n$ be arranged in a sequence $\left\{X_{nk}\right\}$, $k=1,2,3,\dots$, and consider the infinite array

in which the elements of $E_n$ form the $n$th row. The array contains all elements of $S$. As indicated by the arrows, these elements can be arranged in a sequence

$$ x_{11};x_{21},x_{12};x_{31},x_{22},x_{13};x_{41},x_{32},x_{23},x_{14};\dots\tag{*} $$

If any two of the sets $E_n$ have elements in common, these will appear more than once in $(*)$. Hence there is a subset $T$ of the set of all positive integers such that $S\sim T$, which shows that $S$ is at most countable. Since $E_1\subset S$, and $E_1$ is infinite, $S$ is infinite, and thus countable. $\blacksquare$

How does the bolded sentence follow from all previous? In fact, I do not know how the matrix and $(*)$ come into play.