Consider the system of infinite series \begin{align} &F=x+\frac{y^{3^2}}{3}+\frac{x^{3^5}}{3^2}+\frac{y^{3^7}}{3^3}+\frac{x^{3^{10}}}{3^4}+\frac{y^{3^{12}}}{3^5}+\cdots=0 \\ &G=y+\frac{x^{3^3}}{3}+\frac{y^{3^5}}{3^2}+\frac{x^{3^{8}}}{3^3}+\frac{y^{3^{10}}}{3^4}+\frac{y^{3^{13}}}{3^5}+\cdots=0. \end{align}

I want to approximate its zeros using Newton-Raphson process/ any other method.

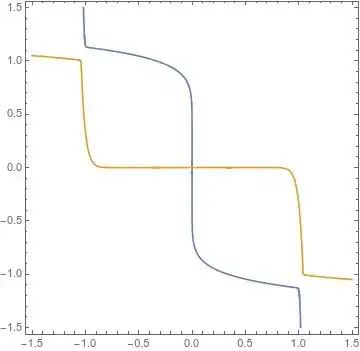

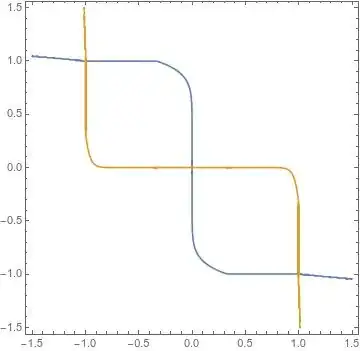

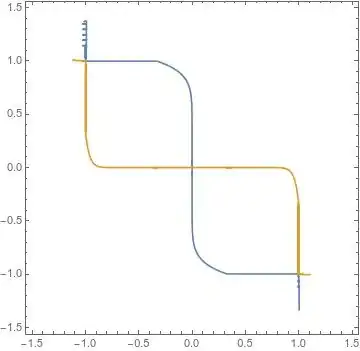

Since the above system consists of infinite series, we don't have technique unless we truncate the system. I am considering the following truncated system \begin{align} &F(x,y)=x+\frac{y^{3^2}}{3}+\frac{x^{3^5}}{3^2}+\frac{y^{3^7}}{3^3}+\frac{x^{3^{10}}}{3^4}=0 \\ &G(x,y)=y+\frac{x^{3^3}}{3}+\frac{y^{3^5}}{3^2}+\frac{x^{3^{8}}}{3^3}+\frac{y^{3^{10}}}{3^4}=0. \end{align}

This one I am going to try at first.

Now in my previous post, I have asked to solve the following system \begin{align} &f(x,y)=x+\frac{y^{2^2}}{2}+\frac{x^{2^5}}{2^2}+\frac{y^{2^7}}{2^3}=0 \\ &g(x,y)=y+\frac{x^{2^3}}{2}+\frac{y^{2^5}}{2^2}+\frac{x^{2^8}}{2^3}=0. \end{align} The Sage code, given by the use @dan_fulea, was

IR = RealField(150)

var('x,y');

f = x + y^4/2 + x^32/4 + y^128/8

g = y + x^4/2 + y^32/4 + x^256/8

a, b = IR(-1), IR(-1)

J = matrix(2, 2, [diff(f, x), diff(f, y), diff(g, x), diff(g, y)])

v = vector(IR, 2, [IR(a), IR(b)])

for k in range(9):

a, b = v[0], v[1]

fv, gv = f.subs({x : a, y : b}), g.subs({x : a, y : b})

print(f'x{k} = {a}\ny{k} = {b}')

print(f'f(x{k}, y{k}) = {fv}\ng(x{k}, y{k}) = {gv}\n')

v = v - J.subs({x : a, y : b}).inverse() * vector(IR, 2, [fv, gv])

Using the initial guess $(-1,-1)$, the N-R process converges at $8$th iteration.

Unfortunately the same code seems to be inefficient to solve the above truncated system $$F(x,y)=0=G(x,y).$$ It seems this system is associated with higher degrees and that is why the above code is efficient. It needs modification.

Is there a more efficient computer code to solve the above truncated system system in N-R method or other numerical methods ?

Thanks