In 2009, Richard Schwartz proved that any obtuse triangle whose largest angle is $\leq100^{\circ}$ has a stable periodic billiard orbit. My question then, is:

How can I reproduce Schwartz's result using a simulation?

More specifically,

How can I develop a numerical method converging to a $(P_0,V_0)$ (initial position, initial direction) giving a Schwartz periodic orbit?

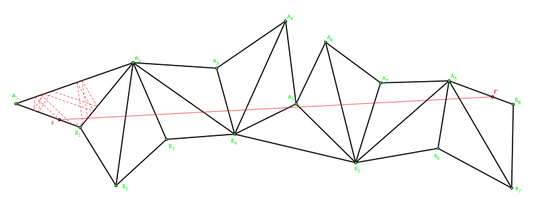

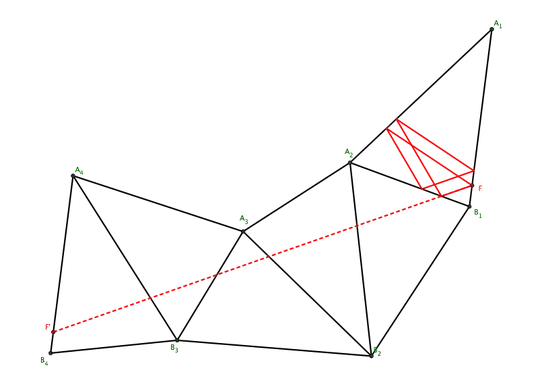

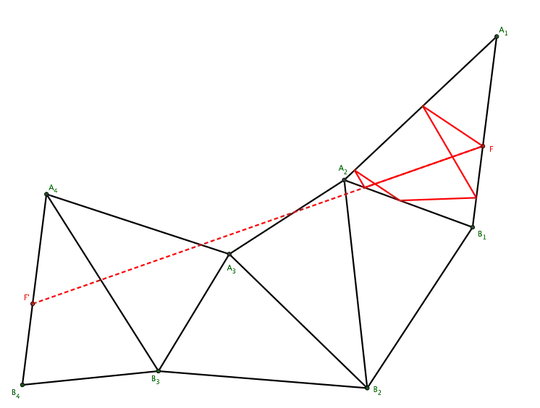

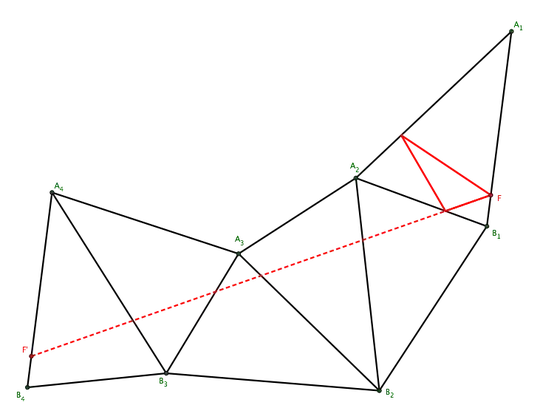

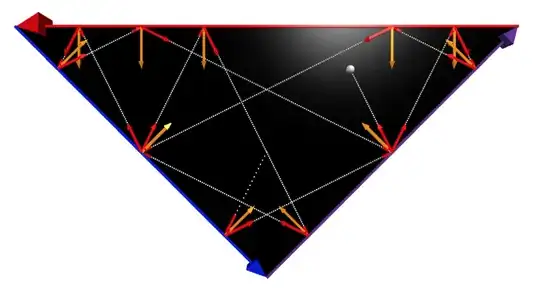

I've created a functioning simulation which produces paths in a triangular billiard table, given the initial position and direction of the ball:

However, I have no idea how to even begin computationally reproducing Schwartz's result. A brute-force approach of supplying the ball with every initial condition

However, I have no idea how to even begin computationally reproducing Schwartz's result. A brute-force approach of supplying the ball with every initial condition (position, direction) for every triangle with angles $100\leq \alpha \leq 180$ is simply infeasible for an infinite search space. Given this, I would very much appreciate any insights from the Math Stack Exchange community for how to go about reproducing this result. And of course, I can make any modifications to my program as necessary.