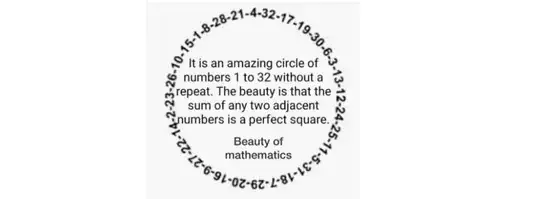

I got this interesting arrangement of numbers from $1$ to $32$ in a group in Facebook-

This being an interesting property to look at, I was trying to figure out whether $32$ is something special, or does this hold for other numbers as well. So, let's say, we want to construct one such circle for a general $n$. My idea was to take any $m\in \mathbb N_n=\{1,2,\dots ,n\}$ and find two different integers $x,y\in\mathbb N_n$ so that both $(m+x)$ and $(m+y)$ are perfect squares. Then, we need to find $x^\prime, y^\prime\in \mathbb N_n$ different from $x$, $y$ and $m$ such that both $(x+x^\prime)$ and $(y+y^\prime)$ are perfect squares. Then, we can continue in this manner.

Now, for any two $a,b\in \mathbb N_n$, we have $2\leq a+b\leq 2n$. So, for our given $m$, when we are looking for the mentioned $x$ and $y$, we only need to check through all the perfect squares in the interval $[m,2n]$. So, to reduce our work, we can take our initial choice $m$ to be equal to $n$.

But, now comes the main problem. Let's say, we want to work it out for $\mathbb N_{33}$. So, let's say, our initial $m$ is $33$. The values of $x$ and $y$ can be from the set $\{3,16,31\}$. The question is, which two of these three to choose so that eventually we don't run into a repitition. Note that, in the $\mathbb N_{32}$ case (which is the one in the diagram), taking $m=32$ leaves us with an advantage of having only two choices $4$ and $17$. But, in the next step, for finding the appropriate $x^\prime$ for $x=4$, we have the choices $\{5,12,21\}$ (since $32$ is already taken). The given diagram uses $x^\prime =21$. I tried using $x^\prime =5$ and then using values of my choice, but soon ran into an unavoidable repitition.

So, is there a way to make more circles with other values of $n$, or does $32$ have some profound property which makes it the only possible choice for $n$? I thought, maybe $32$ being a power of $2$ has to do something with it. So, I tried using $n=2,4,8,16$. But, these are trivially NOT solutions since there aren't enough perfect squares in $[n,2n]$ for these values of $n$. Note that this "not enough squares" angle immediately gives a lower bound of $n\geq 19$ by trial and error. Peter Taylor pointed out in the MathOverflow post that this "not enough squares" argument also rules out $n\le 30$ since $18$ is always a vertex of degree $1$ otherwise. So, we have a lower bound of $n\ge 31$. Also, I was too lazy to even attempt $n=64$.

So, is this case a rare coincidence, or can we have other values of $n$ satisfying this property as well? If there are other values, what family do they belong to? Also, for any case, is that arrangement unique?

Edit: I got one interesting answer that uses graph theory. But, that has a computer program to check that it holds for all $100\geq n\geq 32$. However, I want more "mathy" arguments. I want to see why this happens instead of to only confirm that it happens. I want to know whether it happens for all $n$ or whether there are cases where it breaks down. Please consider these questions as well.

Also, here's the MathOverflow post of the same question. This answer gives two sequences in the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, A071983 and A071984 which seems somewhat relevant.