[This question has lead me to ask a follow up on MathOverflow.]

A recent tweet by John Baez has reminded me of the astonishing fact$^1$ that the Riemann hypothesis (RH) can be disproved by finding a number $n > 5040$ such that $$\frac{\sigma(n)}{n \ln\ln n} > e^\gamma \;,$$ where $\gamma$ is Euler's constant. We can take the logarithms and introduce a function $$s(n) = \ln \frac{\sigma(n)}{n \ln\ln n}$$ such that the bound becomes $s(n) > \gamma$. This is convenient, because if we know the prime factorisation $n = \prod_{q} q^{k_q}$ of a candidate number, we can rather easily compute $$s(n) = \sum_{q} \ln \frac{q^{k_q+1} - 1}{q - 1} - \sum_{q} k_q \ln q - \ln\ln \sum_{q} k_q \ln q \;,$$ without too much numerical trouble.$^2$

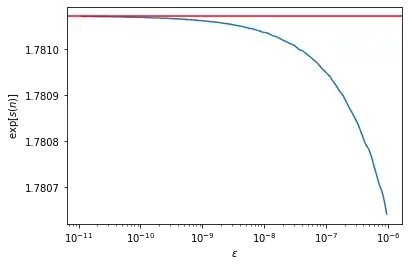

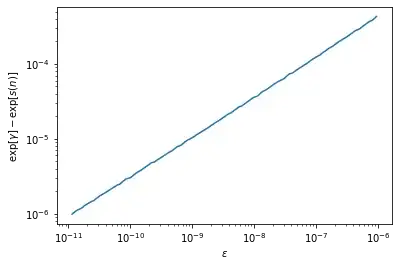

Now, it has been shown that if the RH is false, the inequality will fail to hold for a colossally abundant number. These were introduced by Alaoglu & Erdős (1944) and are defined such that $n$ is colossally abundant if and only if there is $\epsilon > 0$ such that for all $k > 1$ $$\frac{\sigma(n)}{n^{1+\epsilon}} \ge \frac{\sigma(k)}{k^{1+\epsilon}} \;.$$ Importantly, their Theorem 10 gives a simple enumeration of the prime exponents of the colossally abundant number associated with a particular $\epsilon > 0$, $$k_q(\epsilon) = \left\lfloor \frac{\ln \frac{q^{1+\epsilon}-1}{q^{\epsilon}-1}}{\ln q}\right\rfloor - 1 \;.$$ Since all we need to compute the function $s(n)$ are a large list of primes $q$ and their exponents $k_q$, we can pick any $\epsilon > 0$, for example at random, compute the complete list of nonzero $k_q(\epsilon)$, and obtain $s(n)$ rather straightforwardly. The result of a random draw as function of $\epsilon$ is shown here:

It seems to me as if the values $s(n)$ approach the bound in an almost perfectly exponential manner. The curve is noisy, but as far as I can tell only due to the floor function, since everything else appears perfectly smooth.

In what way could specific values of $\epsilon > 0$ make the noise cross the bound to potentially disprove the RH?

More to the point, I don't understand how the structure of the primes comes into play here. The expression in the floor function in $k_q(\epsilon)$ smoothly approaches unity for fixed $\epsilon$ and increasing $q$, so for any $\epsilon$ there is a smallest prime $r$ such that that $k_q = 0$ for all $q \ge r$. In which way can the primes conspire such that a small change $\delta\epsilon$, not big enough to change $r$, changes enough $k_q$ for $q < r$ to make a significant change to $s(n)$?

Even more interestingly, we can ostensibly make the following observation:

For $\epsilon < 0.01$, the function $s(n)$ is monotonically increasing as $\epsilon$ approaches zero.

If this were true, it would mean that the RH can be disproved with the limit $\epsilon \to 0$ of $s(n)$ alone (which is of course a very hard problem). This seems a very analytical problem however, and makes me wonder again how and where the structure of the primes matters in this.

And just to make it perfectly clear: The question is not "does this disprove the RH". The question is "how could this, in principle, disprove the RH".

$^1$ Astonishing, because I can understand the problem even though I know nothing about the RH.

$^2$ If someone is interested in trying, note there is trouble in double precision once $\epsilon$ get to $10^{-9}$. You can rewrite the function $s(n)$ to treat the many, many, many $k_q = 1$ for the largest primes separately, $$s(n) = \sum_{q \colon k_q>1} \ln \frac{q^{k_q+1} - 1}{q^{k_q} \, (q - 1)} + \sum_{q \colon k_q=1} \ln (1 + 1/q) - \ln\ln \sum_{q} k_q \ln q \;.$$ The often available log1p function further helps with $\log(1 + 1/q) = \operatorname{log1p}(1/q)$.