This answer was based on the following: suppose you are dividing integrals $\int g(x,y) dx/\int h(x,y) dx$ and at each $x$, $g(x,y)/h(x,y)$ is decreasing in $y$. Then the combination of these should tend towards $\int g(x,y) dx/\int h(x,y) dx$ decreasing in $y$ too.

If we remove $r$ from the limits by substituting $x = r+u$ and divide the terms we get $r \cos^{-1}\left(\frac{(r+u)^2+r^2-1}{2(r+u)r} \right)$ which if you graph is monotonically decreasing in $r$. So this is our case.

The first part of the problem was three conditions which should be sufficient for this idea to work.

(i) Each individual $g(x,y)/h(x,y)$ should be decreasing in $y$.

(ii) the fractions are ordered from greatest ratio to least least (not necessary, but helpful).

(iii) a fraction with the greater ratio loses more relative size than the fraction with a smaller ratio.

The second part of the problem was finding a transformation which made verifying the conditions possible.

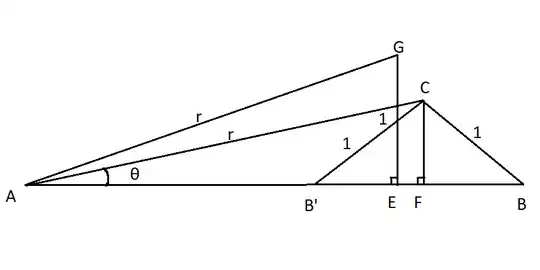

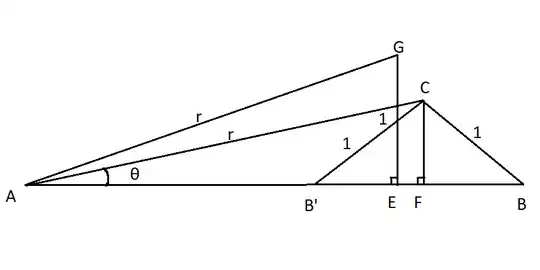

Here is a diagram.

$AB, AB', AE$ are $x$ for different values. By Law of Cosines $1 = r^2 + x^2 - 2rx \cos \theta$ so $\theta = f(x)$.

Note $\theta$ is maximized when $x = AE = \sqrt{r^2-1}$, increasing for $x< AE$, and decreasing for $x> AE$.

Let $y = \pi(x) = FB = x - r \cos \theta = \frac{x^2-r^2+1}{2x}$. $\pi(x)$ will be used to center the integrals.

$\pi(x)$ is a strictly increasing bijection from $[r-1,r+1]$ to $[-1,1]$. It can be shown

$$ \pi^{-1}(y) = y + \sqrt{r^2 + y^2 - 1} $$

$$f(\pi^{-1}(y)) = \cos^{-1}\left(\frac{\sqrt{r^2+y^2-1}}{r}\right) $$

$g(r)$ becomes

\begin{align}

g(r) &= \frac{\int_{-1}^0 rf(\pi^{-1}(y))^2 \pi^{-1}(y)_y \ dy + \int_{0}^1 rf(\pi^{-1}(y))^2 \pi^{-1}(y)_y \ dy}{\int_{-1}^0 f(\pi^{-1}(y)) \pi^{-1}(y)_y \ dy + \int_0^1 f(\pi^{-1}(y)) \pi^{-1}(y)_y \ dy} \\

&= \frac{\int_0^1 rf(\pi^{-1}(y))^2 \left(\pi^{-1}(-y)_y + \pi^{-1}(y)_y\right) \ dy}{\int_0^1 f(\pi^{-1}(y)) \left(\pi^{-1}(-y)_y + \pi^{-1}(y)_y\right) \ dy} \\

&= \frac{\int_0^1 rf(\pi^{-1}(y))^2 \ dy}{\int_0^1 f(\pi^{-1}(y)) \ dy}

\end{align}

This can be integrated in terms of elliptical integrals, but I couldn't make much sense of it.

Denote $A_y(r) = r\cos^{-1}\left(\frac{\sqrt{y^2+r^2-1}}{r} \right)^2$ and $B_y(r)= \cos^{-1}\left(\frac{\sqrt{y^2+r^2-1}}{r} \right)$ for $y\geq 0, r \geq 1$.

We intend to apply the following to the Riemann Sums of $A_y(r)$ and $B_y(r)$.

$\textbf{Claim}$: Suppose $a^{(k)}_i, b^{(k)}_i, i = 1,...,n, \ k = 1, 2$ are positive numbers such that

(1) $a_i^{(k)}/b_i^{(k)} \geq a_j^{(k)}/b_j^{(k)}$ for $i \leq j$

(2) $a_i^{(1)}/b_i^{(1)} \geq a_i^{(2)}/b_i^{(2)}$

(3) $b_i^{(2)}/b_i^{(1)} \leq b_j^{(2)}/ b_j^{(1)} \leq 1$ for $i\leq j$.

Then

$$

\frac{a^{(1)}_1 + \cdots + a^{(1)}_n}{b^{(1)}_1 + \cdots + b^{(1)}_n} \geq \frac{a^{(2)}_1 + \cdots + a^{(2)}_n}{b^{(2)}_1 + \cdots + b^{(2)}_n}

$$

$Proof$. By strong induction on $n$. Case $n=1$ is trivial. For $n=2$

\begin{align}

\frac{a_1^{(1)} + a_2^{(1)}}{b_1^{(1)}+b_2^{(1)}} &= \frac{\frac{a_1^{(1)}}{b_1^{(1)}}b_1^{(1)} + \frac{a_2^{(1)}}{b_2^{(1)}}b_2^{(1)}}{b_1^{(1)}+b_2^{(1)}} \\

&\stackrel{(2)}{\geq} \frac{\frac{a_1^{(2)}}{b_1^{(2)}}b_1^{(1)} + \frac{a_2^{(2)}}{b_2^{(2)}}b_2^{(1)}}{b_1^{(1)}+b_2^{(1)}} \\

&= \frac{a_1^{(2)}}{b_1^{(2)}}(1 - t) + \frac{a_2^{(2)}}{b_2^{(2)}}t

\end{align}

where $t = \frac{1}{b_1^{(1)}/b_2^{(1)} + 1}$. Note because of $(1)$ the last equation is monotonically decreasing in $t$. Also by $(3), \ t \leq \frac{1}{b_1^{(2)}/b_2^{(2)} + 1}$. It follows

\begin{align}

\text{RHS} &\geq \frac{a_1^{(2)}}{b_1^{(2)}}\left(1 - \frac{1}{b_1^{(2)}/b_2^{(2)} + 1} \right) + \frac{a_2^{(2)}}{b_2^{(2)}}\frac{1}{b_1^{(2)}/b_2^{(2)} + 1} \\

&= \frac{a_1^{(2)} + a_2^{(2)}}{b_1^{(2)}+b_2^{(2)}}

\end{align}

as desired.

Case $n= N+1$. Let $c^{(k)} = a_1^{(k)} + \cdots + a_n^{(k)}, \ d^{(k)} = b_1^{(k)} + \cdots + b_n^{(k)}, k=1,2$. We will verify $(1), (2), (3)$ for $c^{(k)}, d^{(k)}, a_{N+1}^{(k)}, b_{N+1}^{(k)}$ and apply case $n=2$.

Since $\frac{a_{n+1}^{(k)}}{b_{n+1}^{(k)}} \leq \frac{a_{i}^{(k)}}{b_{i}^{(k)}}$ by $(1)$, it follows

$$

\frac{c^{(k)}}{d^{(k)}} \geq \frac{a_{n+1}^{(k)}}{b_{n+1}^{(k)}}

$$

This verifies $(1)$. Since case $n=N$ holds

$$

\frac{c^{(1)}}{d^{(1)}} \geq \frac{c^{(2)}}{d^{(2)}}

$$

Also by $(2), \ \frac{a_{n+1}^{(1)}}{b_{n+1}^{(1)}} \geq \frac{a_{n+1}^{(2)}}{b_{n+1}^{(2)}} $. This verifies $(2)$.

Lastly $(3)$ holds since

$$

b_i^{(2)}/b_i^{(1)} \leq b_{n+1}^{(2)}/ b_{n+1}^{(1)} \leq 1, \ \ i = 1,...,{n+1}

$$

implies

$$

\frac{d^{(2)}}{d^{(1)}} = \frac{b_1^{(2)} + \cdots + b_n^{(2)}}{b_1^{(1)} + \cdots + b_1^{(n)}} \leq \frac{b_{n+1}^{(2)}}{b_{n+1}^{(1)}} \leq 1

$$

Applying case $n=2$ verifies case $n=N+1$. $$\tag*{$\blacksquare$}$$

We also claim

$\mathbf{Claim}$:

(i) $A_y(r)/B_y(r)$ is monotonically decreasing in $y$ for fixed $r$.

(ii) $A_y(r)/B_y(r)$ is monotonically decreasing in $r$ for fixed $y$.

(iii) For fixed $r_1 \leq r_2$, $B_y(r_2)/B_y(r_1) \leq 1$ is increasing in $y$.

$Proof$. (i) Note $A_y(r)/B_y(r) = rf(\pi^{-1}(y))$. By construction, on $[0,1], \ \theta = f(\pi^{-1}(-y))$ is decreasing so $A_y(r)/B_y(r) = r \theta$ is.

(ii) The arc $r\theta$ has fixed height $CF = \sqrt{1-y^2}$, but has longest length when $r=1$, with length decreasing and approaching $CF$ as $r$ increases.

(iii)

We have

$$

\frac{B_y(r_2)}{B_y(r_1)} = \frac{f(\pi^{-1}(y))_{r = r_2}}{f(\pi^{-1}(y))_{r=r_1}}

$$

Differentiating

$$

\frac{d}{dy} f(\pi^{-1}(y)) = \frac{-1}{\sqrt{1-y^2}} \frac{y}{\sqrt{r^2+y^2 - 1}}

$$

Then by the quotient rule, verifying $\frac{d}{dy} \frac{f(\pi^{-1}(y))_{r = r_2}}{f(\pi^{-1}(y))_{r=r_1}} \geq 0$ is equivalent to checking

$$

-\cos^{-1}\left(\frac{\sqrt{r_1^2 + y^2-1}}{r_1} \right)\frac{1}{\sqrt{y^2 + r_2^2 -1}} + \cos^{-1}\left(\frac{\sqrt{r_2^2 + y^2-1}}{r_2} \right)\frac{1}{\sqrt{y^2 + r_1^2 -1}} \geq 0

$$

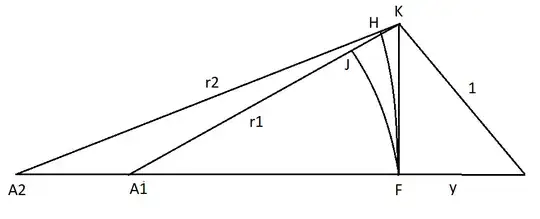

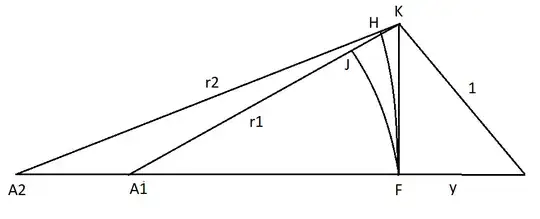

Note $AF = \sqrt{r^2+y^2-1}$. The inequality states the arc $FH$ is greater than the arc $FJ$ in the following diagram.

This is true since if $\theta =\angle FA_2K$ then arc $FH = \sqrt{1-y^2} \ \theta \cot \theta$ is decreasing from $\theta = 0$ to $\pi/2$. The claim follows.

Writing $g(r)$ as a quotient of Riemann Sum's

$$

g(r) = \lim_{\max \Delta x_i \rightarrow 0} \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n A_{x_i^*}(r) \Delta x_i}{\sum_{k=1}^n B_{x_i^*}(r) \Delta x_i}

$$

where $x_k^*$ are points in the intervals associated with $\Delta x_k$.

Let $r_2 \geq r_1$. In the first claim if we identify $a_i^{(k)} = A_{x_i^*}(r_k), b_i^{(k)} = B_{x_i^*}(r_k)$ then (1), (2), and (3) follow from (i), (ii), and (iii).

Applying the first claim

$$

\frac{\sum_{i=1}^n A_{x_i^*}(r_1) \Delta x_i}{\sum_{k=1}^n B_{x_i^*}(r_1) \Delta x_i} \geq \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n A_{x_i^*}(r_2) \Delta x_i}{\sum_{k=1}^n B_{x_i^*}(r_2) \Delta x_i}.

$$

Taking the limit as $\Delta x_i \rightarrow 0$ gives $g(r_1) \geq g(r_2)$ as desired.