Suppose that we have a convex polyhedron $P$, such that the symmetry group of $P$ acts transitively on its vertices, edges, and faces (that is, it is isogonal, isotoxal, and isohedral). It then follows that $P$ is one of the Platonic solids, which have a number of equivalent definitions but usually includes some stipulation that the faces are regular. (Once you have regular faces plus these symmetry conditions, most other properties follow easily.)

This can be shown via a rather gross casework argument on the number of sides at each face. By face-transitivity, all faces are congruent (in fact, we only need that the polyhedron be monohedral for this). By edge-transitivity, said faces are equilateral polygons. Then we break into cases by the number of sides of the polygons:

If the faces are triangles, being equilateral implies being regular.

If the faces are non-regular equilateral quadrilaterals, they are rhombi. Then, at every vertex there must be an equal number of "skinny" and "wide" angles meeting, and there must be at least 3 faces meeting at a vertex. But then there are at least two skinny and two wide angles (since we assume the angles are different), so the angles at each vertex add up to at least 360 degrees, which is not possible in a convex polyhedron.

If the faces are non-regular equilateral pentagons, then they have angles which are not all the same; however, each vertex must have the same angles around it, so each vertex has a proportional fraction of the angles of the pentagons. But for any distribution other than the uniform one, the only way to have a proportional amount of every angle is to have some $n$ copies of every angle with multiplicity, since $5$ is prime. (E.g. if there are $2$ angles of one size and $3$ of another, we can't get a $2:3$ ratio without having at least $5$ angles at every vertex.) But the angles of a pentagon add to more than $360^\circ$, so we can't have them all at once.

If the faces are hexagons or higher, they cannot form a topological sphere by Euler's formula.

However, I don't like this proof very much; I walk away from it with no understanding of why this behavior occurs, and it certainly doesn't suggest any generalizations to other dimensions (where I believe the analogous statement - that transitivity on every degree of cell in a convex polytope implies regularity - is true, though I would appreciate a reference for this fact).

Is there a natural or more elegant proof of this statement?

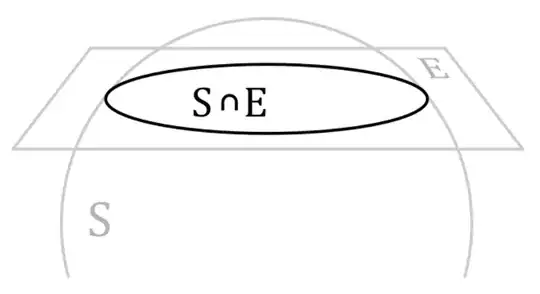

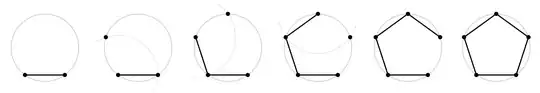

One thing to note is that any proof must somehow use the fact that we are working on the sphere. In the case of planar tilings, the corresponding implication is false: being transitive on faces, vertices, and edges does not imply that one is looking at a tiling of regular polygons! As a counterexample, consider a rhombic tiling like this one:

As another aside, relaxing any one of these conditions allows for polyhedra whose faces are not congruent regular polygons: the rhombic dodecahedron is face-transitive and edge-transitive, an isosceles tetrahedron is face-transitive and vertex-transitive, and the cuboctahedron is edge-transitive and vertex-transitive.