Suggested by @Ailurus (thanks!!!)

Excerpted from: PRINCIPAL AXES AND BEST-FIT PLANES, WITH APPLICATIONS, by Christopher M. Brown, University of Rochester.

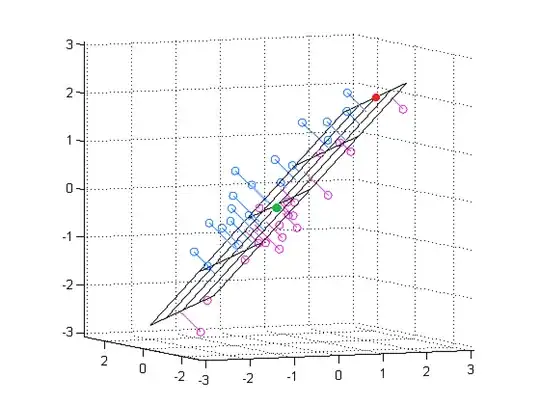

Consider the problem of finding a plane which “best fits” a swarm of weighted points. If the points are in n-space, the plane is a hyperplane; we will refer to it as a plane. Represent k-weighted points in n-space by row n-vectors x$_{\mathrm{i}}$, i=1, 2, ..., k; let the weight of the ith point be w$_{\mathrm{i}}$. Represent an n-1-dimensional subspace Π of n-space (a hyperplane) by a unit n-vector $\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}$ normal to Π and a point $\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}$ in Π. In the "sequel" (the following equations), all summations run from 1 to k.

The signed perpendicular distance from x$_{\mathrm{i}}$ to the plane (Π) is:

\begin{equation*}

\mathrm{d}_{\mathrm{i}Π }=\left(\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}-\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\right)\cdot \vec {\boldsymbol{z}}.

\end{equation*}

The error measure we wish to minimize is the sum over all points of the square of this distance times the weight (mass) of the point, i.e.

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{c}

e=\sum _{i}\left(\left(\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}-\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\right)\cdot \vec {\boldsymbol{z}}\right)^{2}w_{i}=\sum _{i}\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}\left(\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}-\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\right)^{T}\left(\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}-\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\right)\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}^{T}w_{i}=\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}\boldsymbol{M}\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}^{T}. \left(1\right)

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

The equation (1), ${\boldsymbol{M}}$ is a real, symmetric n x n matrix, sometimes called the "scatter matrix" of the points.

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{c}

\boldsymbol{M}=\sum _{i}w_{i}\left(\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}-\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\right)^{T}\left(\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}-\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\right). \left(2\right)

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

First, we show that the best-fit plane passes through the center of mass (C. of M.) of the points. (The answer to the original question.)

$\underline{Proposition 1}.$ For ${e}$ of equation (1) to be minimized, the plane must pass through the C. of M. of the point swarm. Thus, in equation (1), ${e}$ may attain a minimum when $\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}$ is the C. of M.

$\underline{Proof}$:

\begin{equation*}

e=\sum _{i}w_{i}\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}\left(\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}\cdot \vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}\right)\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}^{T}-2\sum _{i}w_{i}\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}\left(\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}\cdot \vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\right)\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}^{T}+\sum _{i}w_{i}\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}\left(\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\cdot \vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\right)\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}^{T}.

\end{equation*}

Since $\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}\vec {\boldsymbol{z}}^{T}=1$ by definition,

\begin{equation*}

\frac{\partial e}{\partial \vec {\boldsymbol{v}}}=-2\sum _{i}w_{i}\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}+2\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}\sum _{i}w_{i};

\end{equation*}

Setting $\frac{\partial e}{\partial \vec {\boldsymbol{v}}}=0$ implies

\begin{equation*}

\vec {\boldsymbol{v}}=\frac{\sum _{i}w_{i}\vec {\boldsymbol{x}}_{i}}{\sum _{i}w_{i}},

\end{equation*} which is the center of mass.

So, it is possible to find a point in the best-fit plane; the plane would be determined completely if a normal vector for it could be obtained. (The original paper explains how to do this in the subsequent propositions/proofs.)