Consider an unconstrained matrix $Y\in{\mathbb R}^{2\times n}$ and with magnitude $\mu=\sqrt{\operatorname{tr}(Y^TY)}$.

Using a colon to denote the trace product, i.e. $\,A:B=\operatorname{tr}(A^TB),\,$ we can differentiate the magnitude as

$$\mu^2=Y:Y \implies\mu\,d\mu=Y:dY$$

Collect the $x_i$ vectors into the columns of a matrix, $X\in{\mathbb R}^{2\times n}$

Then the elements of the Grammian matrix $\,G=X^TX\,$ equal the dot products of the vectors and the main diagonal contains their squared lengths.

Thus the problem's constraint can be expressed as the trace of $G$

$$1 = \operatorname{tr}(G) = X:X$$

and $X$ can be construct from $Y$ such that this constraint is always satisfied

$$\eqalign{

X &= \mu^{-1}Y \quad\implies X:X = \mu^{-2}(Y:Y) = 1 \\

dX &= \mu^{-1}dY - \mu^{-3}Y(Y:dY) \\

}$$

Columnar distances can be calculated from $G$ and the all-ones vector ${\tt1}$

$$\eqalign{

G &= X^TX \;=\; \tfrac{Y^TY}{Y:Y} \\

g &= \operatorname{diag}(G) \\

A_{ij} &= \|x_i-x_j\| \quad\implies A= g{\tt1}^T + {\tt1}g^T - 2G \\

B &= A+I,\quad C= B^{\odot-3/2} \\

L &= \operatorname{Diag}(C{\tt1})-C \;=\; I\odot(C{\tt11}^T)-C \\

}$$

Adding the identity matrix gets rid of the zero elements on the main diagonal, and allows the calculation of the inverse Hadamard $(\odot)$ powers needed for the objective function and its derivative.

$$\eqalign{

f &= {\tt11}^T:B^{\odot-1/2} \;-\; {\tt11}^T:I \\

df &= -\tfrac{1}{2}C:dB \\

&= \tfrac{1}{2}C:(2\,dG - dg\,{\tt1}^T - {\tt1}\,dg^T) \\

&= C:dG - \tfrac{1}{2}(C{\tt1}:dg+{\tt1}^TC:dg^T) \\

&= C:dG - C{\tt1}:dg \\

&= \Big(C - \operatorname{Diag}(C{\tt1})\Big):dG \\

&= -L:dG \\

}$$

Pause here to note that $L$ is the Laplacian of $C$ and the matrices $(A,B,C,G,L)$ are all symmetric.

$$\eqalign{

df &= -L:(dX^TX+X^TdX) \\

&= -2L:X^TdX \\

&= -2XL:dX \\

&= -2\mu^{-1}YL:(\mu^{-1}dY - \mu^{-3}Y(Y:dY)) \\

&= 2\mu^{-2}\Big(\mu^{-2}(YL:Y)Y - YL\Big):dY \\

&= 2\mu^{-2}\Big((G:L)Y - YL\Big):dY \\

\frac{\partial f}{\partial Y}

&= 2\mu^{-2}\Big((G:L)Y - YL\Big) \\

}$$

Since $Y$ is unconstrained, setting the gradient to zero yields a first order conditon for optimality.

$$\eqalign{

YL &= (G:L)Y \;=\; \lambda Y \\

LY^T &= \lambda Y^T \\

}$$

This has the form of an eigenvalue problem, except that $L$ is a nonlinear function of $Y$.

However, the relationship does reveal that both rows of $Y$ must be eigenvectors of $L$ associated with some eigenvalue of multiplicity $>1$.

Since $L$ is a Laplacian, ${\tt1}$ is guaranteed to be an eigenvector of $L$ associated with $\lambda=0.$

If $\operatorname{rank}(L)\le(n-2)$ then there are additional vectors in the nullspace of $L$ which can be used in the second row. When plotted such a solution would appear as a vertical line, since the first component of each $x_i$ vector will be identical.

Summary

- The original constrained problem can be converted into an unconstrained

problem.

- All solutions must satisfy FOCs in the form of

a nonlinear EV problem.

- Despite their nonlinear nature, one eigenpair

$\big(\{\lambda,v\}=\{0,{\tt1}\}\big)$ is already known.

- Iff a second eigenpair $\{0,v\}$ exists, then points of the solution

$Y=\big[{\tt1}\;\;v\big]^T$ lie on a line.

- In any event, two $v_k$ with the same $\lambda$ are needed for

a solution $Y=\big[v_1\;\;v_2\big]^T$

- SOCs will need to be calculated and evaluated to determine if a

particular FOC solution represents a (local) minimum or maximum.

Another way to approach the problem is to treat each $x_i$ as a complex scalar rather than a real vector. Then instead of the matrix $X\in{\mathbb R}^{2\times n}$ the analysis would focus on the complex vector $z\in{\mathbb C}^{n}$.

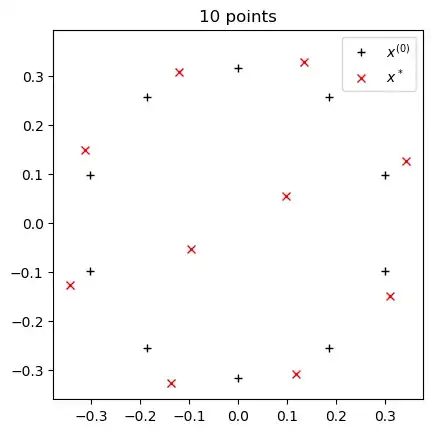

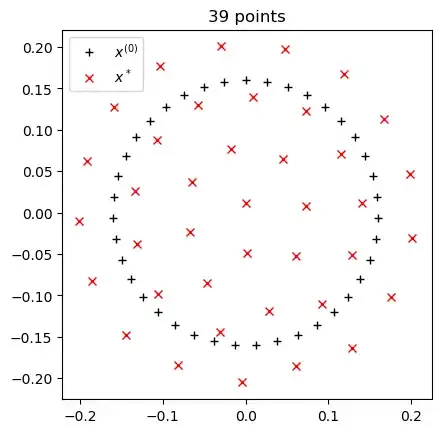

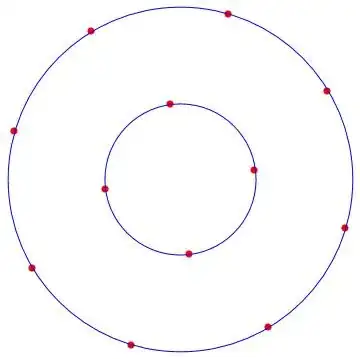

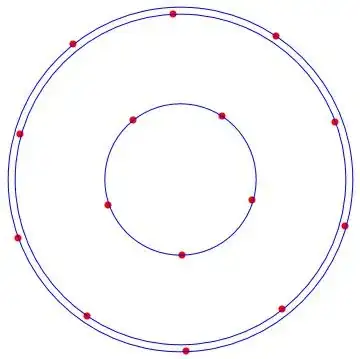

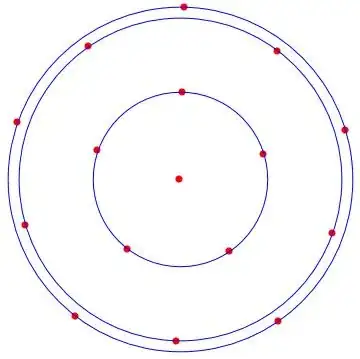

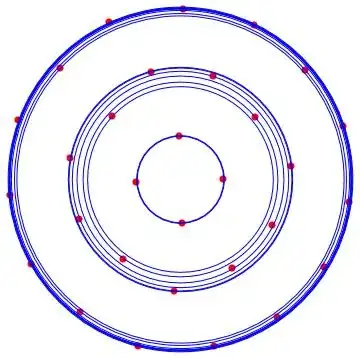

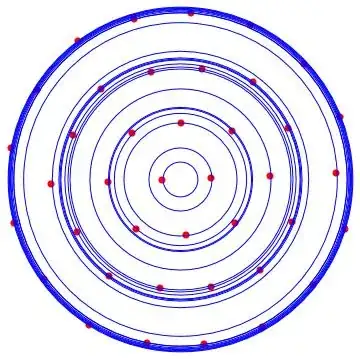

It's a straightforward exercise to numerically verify that the vertices of a regular polygon $(Y_{poly})$ satisfy the nonlinear EV equation.

It's also easy to perturb $Y_{poly}$ and check for nearby $Y$'s with a smaller objective. This verifies that $Y_{poly}$ is a minimum without needing to find the SOCs.

#!/usr/bin/env julia

using LinearAlgebra;

n = 5 # a pentagon

u,v = ones(n,1), 2*pi*collect(1:n)/n

c,s = cos.(v+u/n), sin.(v+u/n) # add u/n to avoid 0-elements

Y = [c s]'; X = Y/norm(Y); G = X'X; g = diag(G);

A = g*u' + u*g' - 2*G

B = A+I; C = B.^(-3/2); L = C - Diagonal(vec(C*u));

# verify that Y solves the EV equation (via element-wise quotient)

Q = (L*Y') ./ Y'

-15.3884 -15.3884

-15.3884 -15.3884

-15.3884 -15.3884

-15.3884 -15.3884

-15.3884 -15.3884

# the eigenvalue is -15.3884

# now verify that the constraint is satisfied

tr(G)

0.9999999999999998

# objective function

function f(Y)

m,n = size(Y)

X = Y/norm(Y); G = X'X; g,u = diag(G), ones(n,1)

A = g*u' + u*g' - 2*G; B = A + I

return sum(B.^(-0.5)) - n

end

# evaluate at *lots* of nearby points

fY,h = f(Y), 1e-3 # "nearby" is defined by h

extrema( [f(Y+randn(size(Y))*h)-fY for k=1:9999] )

(2.056884355283728e-6, 0.00014463419313415216)

# no negative values ==> f(Y) is a minimum

#