Here is one solution I came upon by myself. I am not really trusting myself if it works, so I am grateful for your feedback.

First some definitions: Suppose we have a class $X$ together with a map $r:\mathcal{P}(X) \to X$. Call a subclass $C \subseteq X$ inductive if for any subset $T\subseteq C$ there is also $s(T) \in C$. Clearly, the intersection of an arbitrary familiy of inductive subclasses is inductive. So we get a hull operator and can define

$$ M(X) := \bigcap \lbrace \ \text{inductive subclasses of}\ X \rbrace$$

We also get another map

$$ R : \mathcal{P}(\mathcal{P}(X)) \to \mathcal{P}(X) \ ,\quad C \mapsto \bigcup_{T \in C} (T \cup \lbrace s(T)\rbrace) $$

I define

$$ I(X) := M(\mathcal{P}(X)) = \bigcap \lbrace \ \text{inductive subclasses of}\ \mathcal{P}(X) \rbrace$$

and this class will be of great importance. While the idea of $M(X)$ is to define the largest subclass of $X$ reachable by transfinite counting, the idea behind $I(X)$ is to keep track of that counting and remember the "initial sets" (therefore the letter "I") of numbers already counted. Be restricting the original map $r$ we get a diagram

$$ I(X) \xrightarrow{r} X$$

Here are my "transfinite peano axioms" for the class of ordinals: The ordinals form a class $\Omega$ together with a "successor function" $s : \mathcal{P}(\Omega) \to \Omega$ such that the following holds:

- For any subset $T \in \mathcal{P}(\Omega)$ we have $s(T) \notin T$. (This corresponds to the Peano axiom concerning $0$ not being in the image of the successor function. While that Peano axiom ensures, that $\mathbb{N}$ not only consists of one element, the transfinite equivalent here ensures, that $\Omega$ is a proper class. So both axioms are about size)

- The restricted successor function $s : I(\Omega) \to \Omega$ is injective. (This corresponds to the Peano axiom concerning the successor function to be injective. It ensures that the process of (transfinite) counting does not end up in a circle)

- ("transfinite induction axiom") If there is a subclass $C \subseteq \Omega$ such that for any subset $T \subseteq C$ with $T\in I(\Omega)$ there is also $s(T) \in C$, then we already have $T=\Omega$. (This corresponds to the induction axiom. It ensures that the process of (transfinite) counting exhausts the entire class).

Make sure yourself by using the transfinite induction axiom, that the restricted successor function $s:I(\Omega) \to \Omega$ is surjective, so, combined with the second axiom, bijective. Note that the von Neumann model makes this cheap, because each von Neumann ordinal is the successor of the set of its elements. For some ordinal $\sigma \in \Omega$, I will write

$$ P_\sigma := s^{-1}(\sigma) $$

for the "set of predecessors" of $\sigma$. Bijectivity of $s$ means, that the induction axiom can be formulated as: "Is $T\subseteq \Omega$ a subclass, such that for any $\sigma \in \Omega$ with $P_\sigma \subseteq T$ we already have $\sigma \in T$, then $T=\Omega$."

Lemma: For any two ordinals $\sigma, \varrho \in \Omega$ with $\sigma \in P_\varrho$, we have $P_\sigma \subseteq P_\varrho$.

Proof: We do induction on $P_\varrho$ and use the inductive nature of the definition of $I(\Omega)$ so that we only have to show that the class

$$ C := \lbrace T \in I(\Omega) \mid \forall \sigma \in \Omega : \sigma \in T \to P_\sigma \subseteq T \rbrace $$

is an inductive subclass of $\mathcal{P}(\Omega)$. Let $S \subseteq C$ be a subclass and $\sigma \in \Omega$ with $\sigma \in \bigcup_{T\in S} (T \cup \{s(T)\})$. So there exists some $T_0\in S$ with $\sigma \in T_0 \cup \lbrace s(T_0)\rbrace $ In case of $\sigma = s(T_0)$ we would have $P_\sigma = T_0 \subseteq \bigcup_{T\in S} (T \cup \{s(T)\})$. In case $\sigma \in T_0 \in S\subseteq C$ we would have $P_\sigma \subseteq T_0 \subseteq \bigcup_{T\in S} (T \cup \{s(T)\})$. So $C$ is indeed inductive and we get $C=I(\Omega)$.

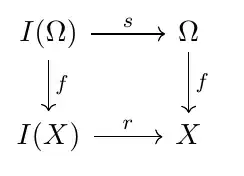

Now comes the universal property of $\Omega$: For any class $X$ together with a map $r: \mathcal{P}(X) \to X$, there exists a unique map $f : \Omega \to X$, such that

$$ f(s(T)) = r(f(T)) \qquad\qquad T \in I(\Omega) $$

which means, that the diagram

commutes. Proof:

Define a class of maps

$$ M := \lbrace g : P \to X \mid P \in I(\Omega),\ \forall \sigma \in P : g(\sigma) = r(g(P_\sigma)) \rbrace $$

Note that this definition makes sense, because if $\sigma \in P \in I(\Omega)$ then, by the above lemma, there is also $P_\sigma \subseteq P$.

First proof step: For any $g,h \in M$ and $\sigma \in \text{dom}(g) \cap \text{dom}(h)$ we have $g(\sigma)=h(\sigma)$. Proof is per induction on $\sigma$. Suppose the claim being correct for all elements of $P_\sigma$. If now $\sigma \in \text{dom}(g) \cap \text{dom}(h)$ we have $P_\sigma \subseteq \text{dom}(g) \cap \text{dom}(h)$, the inductive assumption tells us $g \vert_{P_\sigma}= h \vert_{P_\sigma}$ and we get

$$ g(\sigma) = r(g(P_\sigma)) = r(h(P_\sigma)) = h(\sigma) $$

Second proof step: For any $\sigma \in \Omega$, there exists a map $g \in M$ with $\sigma \in \text{dom}(g)$. Proof is again per induction on $\sigma$. Suppose the claim being true for all elements of $P_\sigma$. Because $I(\Omega)$ is inductive, we have

$$ B := P_\sigma \cup \lbrace \sigma\rbrace \in I(\Omega) $$

Now define a map $ g : B \to X $ by

- $g(b) := h(b)$ if $b \in P_\sigma$ and $h \in M$ is any function with $b \in \text{dom}(h)$. This $h$ exists per inductive assumption and the whole thing is well defined by the first step of the proof.

- $r(g(P_\sigma))$ if $b=\sigma$.

We need to verify that $g \in M$: By definition we have $g(\sigma) = r(g(P_\sigma))$. For each $\varrho \in P_\sigma$ we have $g(\varrho) = h(\varrho) = r(h(P_\varrho)) = r(g(P_\varrho))$. So, indeed $g \in M$.

Third proof step: Define the function $f: \Omega \to X$ by setting $f(\sigma)$ to the value $g(\sigma)$ of any $g \in M$ with $\sigma \in \text{dom}(g)$. Thats it. $f$ is unique by the first proof step. QED

Now lets define addition of ordinals. Therefore let $X$ be an arbitrary class with a map $r : \mathcal{P}(X) \to X$. Define another map:

$$ g : \mathcal{P}(\text{Maps}(X,X)) \to \text{Maps}(X,X) \ , \quad T \mapsto (\sigma \mapsto s(\lbrace t(\sigma) \mid t \in T \rbrace)) $$

with the exception $g(\emptyset) := \text{id}_X$. The universal property gets us a unique map $f : \Omega \to \text{Maps}(X,X)$ and we define

$$x + \sigma := f(\sigma)(x) \qquad\qquad \sigma \in \Omega,\ x \in X $$

which is the element of $X$ one obtains by "iterating the function $r$ on $x$ $\sigma$ times". In the special case $X=\Omega$, we get the addition of ordinals.

Here is an incomplete idea on how to proof that any well-ordered set can be embedded to an initial segment of $\Omega$: If $X$ is a well-ordered set, we get a canonical function

$$ \mathcal{P}(X) \to X \ ,\ T \mapsto \ \text{smallest element of}\ X \setminus T $$

and define $r(X)$ as some member of $X$ (its irrelevant, which one you choose). Universal property lets us get a unique map $f:\Omega \to X$. Assume that there is no $\sigma \in \Omega$ with $f(P_\sigma) =X$. Then (I wasnt yet able to show that) $f$ is injective so we can define a surjective left inverse of $f$. The axiom of replacement concludes that $\Omega$ is a set because $X$ is. But its an easy consequence of the first axiom, that $\Omega$ is a proper class.