I'm trying to prove a standard result: for a positive $n \times n$ matrix $A$, the powers of $A$ scaled by its leading eigenvalue $\lambda$ converge to a matrix whose columns are just scalar multiples of $A$'s leading eigenvector $\mathbf{v}$. More precisely, $$ \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \left(\frac{A}{\lambda}\right)^k = \mathbf{v}\mathbf{u},$$ where $\mathbf{v}$ and $\mathbf{u}$ are the leading right and left eigenvectors of $A$, respectively (scaled so that $\mathbf{u}\mathbf{v} = 1$).

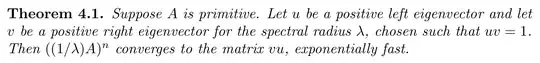

These notes give a nice compact proof, pictured below. (It covers the more general case where $A$ is primitive, but I'm happy to assume it's positive for my purposes.)

I'm stuck on the highlighted step. Having established the existence of a matrix $M$ that (a) fixes $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{v}$, and (b) annihilates all other generalized eigenvalues of $A$, how do we know $M$ is unique? Why couldn't there be other matrices satisfying (a) and (b)?

I don't know much about generalized eigenvectors. I gather they're linearly independent, hence form a basis for $\mathbb{R}^n$. So each column of $M$ must be a unique linear combination of $A$'s generalized right eigenvectors. Is there some path I'm not seeing from there to the conclusion that only one matrix can satisfy both (a) and (b)?