I hold a masters in computer science from one of the worlds top universities and until today I thought I more or less know basic math.

I'm sure you guys all know these click-bait simple "90% of people can't solve this equation" posts on facebook where everyone starts to argue over a simple equation (and I DEFINITELY don't want to kick off one of those - but I'd like to discuss the roots of this confusion).

So today there was another one of those:

6/2(1+2)

Based on what I learned and applied throughout all my years in university, this equals 9, since brackets are evaluated first and then it's left to right, since division and multiplication have the same operator precedence.

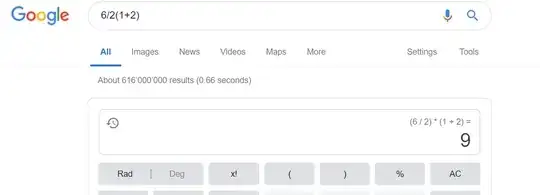

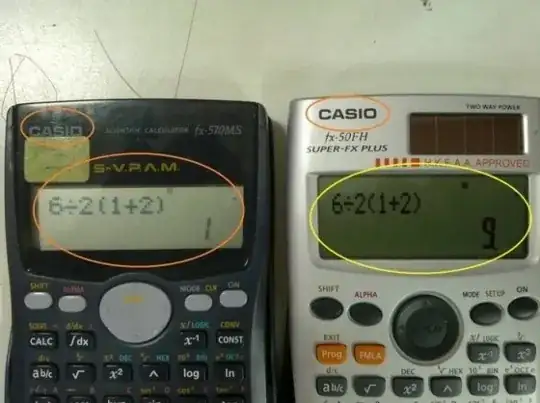

Wolfram Alpha agrees with that:

and my texas instruments agrees with that too. So it's 9, right?

Well today I came across a claim I hadn't heard before, which is "implied multiplication takes precedence over both explicit multiplication and division" - so by that rule it would not be left to right in the above example, but the implied multiplication would be evaluated before the division, which would mean that

6/2(1+2) == 1 != 6/2*(1+2)

So, are google, wolfram alpha and my calculator all wrong (they by the way also yield 9 if ÷ is used instead of /)?

The only thing i found on the issue so far is this statement on Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_operations):

Mixed division and multiplication: Similarly, there can be ambiguity in the use of the slash symbol / in expressions such as 1/2x.[5] If one rewrites this expression as 1 ÷ 2x and then interprets the division symbol as indicating multiplication by the reciprocal, this becomes:

1 ÷ 2 × x = 1 × 1/2 × x = 1/2 × x.

With this interpretation 1 ÷ 2x is equal to (1 ÷ 2)x.1[6] However, in some of the academic literature, multiplication denoted by juxtaposition (also known as implied multiplication) is interpreted as having higher precedence than division, so that 1 ÷ 2x equals 1 ÷ (2x), not (1 ÷ 2)x. For example, the manuscript submission instructions for the Physical Review journals state that multiplication is of higher precedence than division with a slash,[7] and this is also the convention observed in prominent physics textbooks such as the Course of Theoretical Physics by Landau and Lifshitz and the Feynman Lectures on Physics.[a]

So one thing this tells me is clearly AVOID IMPLIED MULTIPLICATION

but what is internationally actually 'more correct and less wrong'? Also, I don't fully see how ÷ vs. / is relevant to this question?