[I edited the question and put stronger emphasis on "constant curvature" than on "naturalness".]

One of the most prominent problems of ancient mathematics was the squaring of the circle: to construct the square with the same area as a given circle.

A related problem is linearizing the circle: to find a natural transition between a given line segment of length $L$ (having constant curvature $0 = 1/\infty$) and the circle with circumference $U = 2\pi R = L$ (with constant curvature $1/R$) going through circle segments of length $L$ (with intermediate constant curvatures $1/R'$, $\infty > R' > R$).

The question is: Along which paths do the points of the line segment move to finally yield the circle?

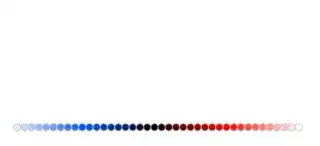

This is how the transition looks like:

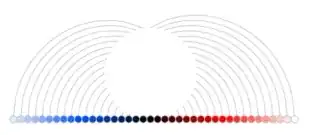

The points of the line segments follow these paths:

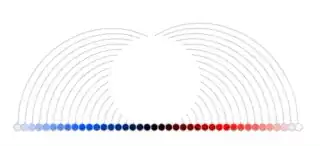

as can be seen here:

To be honest: Even though these paths look very much like circle segments, I'm not quite sure and I didn't define them by an explicit formula (which I didn't have at hand) but heuristically using some support points and splining.

My questions are:

Are these paths really circle segments?

If so: How to parametrize them?

If not so: What kind of curves are they otherwise?

Please allow me – freely associating – to compare the pictures above with this (artificially symmetrized) picture of The Great Wave off Kanagawa