Several questions on this cite concern themselves with the operator $T:\ell^2(\mathbb N)\to\ell^2(\mathbb N)$ where $T(x_n)_{n=1}^\infty=(r_nx_n)_{n=1}^\infty$. Here the sequence $\{r_n:n\in\mathbb N\}\subset M\subset\mathbb C$ is dense in the closed and bounded set $M$. These questions concern themselves with the continuous nature of the operator $T$ as well as the fact that $\sigma(T)=M$. Some of these questions include the following:

Show that $A:\ell^2(\mathbb N)\to\ell^2(\mathbb N)$ where $A(e_n)=\lambda_ne_n$ is bounded.

Prove $\forall$ compact $M:\ M \subset C\quad \exists A:l_2\rightarrow l_2, \sigma(A)=M$

Operator whose spectrum is given compact set

One will note that rather than having $T(x_n)_{n=1}^\infty=(r_nx_n)_{n=1}^\infty$, we could also have our operator defined by $T(e_n)_{n=1}^\infty=(r_ne_n)_{n=1}^\infty$, where $\{e_n\}_{n=1}^\infty$ is the usual basis for $\ell^2(\mathbb N)$.

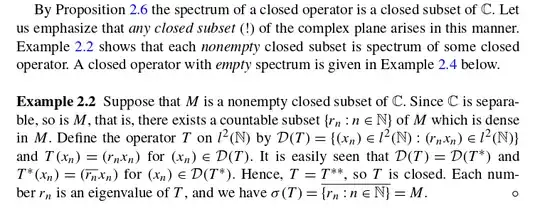

I am interested in this example for the case when $T:\mathcal D(T)\subseteq \ell^2(\mathbb N)\to\ell^2(\mathbb N)$ is potentially unbounded but at least closed. The following is an excerpt from Unbounded Self-adjoint Operators on Hilbert Space by Konrad Schmüdgen. The example contained within the excerpt details that an arbitrary nonempty closed subset $M\subset\mathbb C$ is the spectrum for some closed operator.

In trying to tackle the closed analogue to the hitherto often discussed bounded case, I am finding it hard to grasp and show the following points:

- What difference is there - if any - in requiring that $\mathcal D(T)=\{(x_n)\in\ell^2(\mathbb N):(r_nx_n)\in\ell^2(\mathbb N)\}$ over stipulating that $M\subset\mathbb C$ be compact? As noted in the opening, we often encounter the requirement that $M\subset\mathbb C$ be compact when $T$ is bounded. Interestingly, requiring that $\mathcal D(T)=\{(x_n)\in\ell^2(\mathbb N):(r_nx_n)\in\ell^2(\mathbb N)\}$ just ensures that $T$ is bounded - so are both stipulations equivalent?

- How does one use the fact that $(r_nx_n)\in\ell^2(\mathbb N)$ in the definition of $\mathcal D(T)$ to show that $T:\mathcal D(T)\subseteq \ell^2(\mathbb N)\to\ell^2(\mathbb N)$ is closed? I feel that this is obvious since $T$ acts on all of $\ell^2(\mathbb N)$, but how do I demonstrate that the limit, $x=(x_m)_{m=1}^\infty\in\ell^2(\mathbb N)$, of any convergent sequence $(x_n)_{n=1}^\infty\subset\mathcal D(T)$ satisfies that '$(r_mx_m)\in\ell^2(\mathbb N)$'?

- What is the difference between defining $Tx_n=r_nx_n$ and defining $Te_n=r_ne_n$, as has been propositioned in similar questions? In particular, I feel that this point is best considered when taken with the next question ...

- How, exactly, do we see that $\{r_n:n\in\mathbb N\}\subset M$ is contained within $\sigma(T)$? In particular, I don't see how $Tx_n=(r_nx_n)=(r_1x_1, r_2x_2, r_3x_3,\dots)$ has anything to do with the eigenvalue problem; in particular, if we were interested in showing that this was included in the spectrum why don't we look at $Tx=\lambda x=(\lambda x_1, \lambda x_2, \lambda x_3, \dots)$? It just seems to me that regarding $Tx_n=(r_nx_n)=(r_1x_1, r_2x_2, r_3x_3,\dots)$ seems to say that this whole sequence $(r_n)_{n=1}^\infty$ is an eigenvalue, rather than that each of its components is an eigenvalue. Is this where it makes more sense to look at the operator $Te_n=(r_ne_n)?$