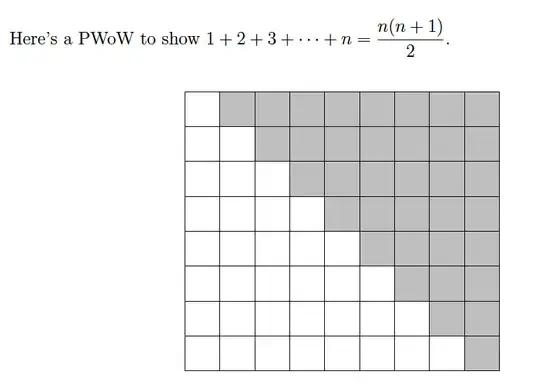

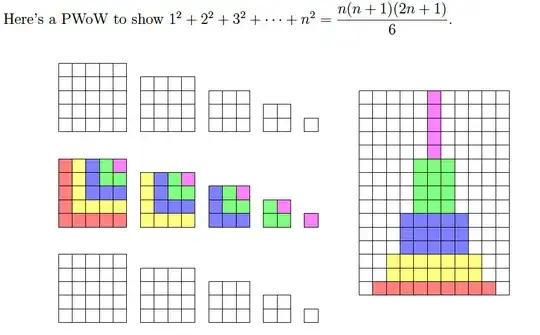

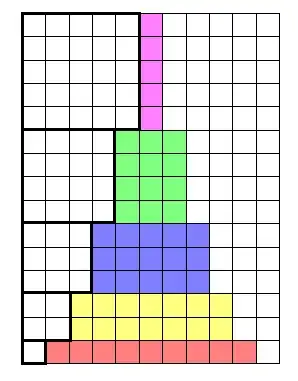

I understand how to derive the formulas for sum of squares, consecutive squares, consecutive cubes, and sum of consecutive odd numbers but I don't understand the visual proofs for them.

For the second and third images, I am completely lost.

For the first one I can see that there are $(n+1)$ columns and $n$ rows. I'm assuming that the grey are even and that the white are odd or vice versa? So in order to have an even amount of odds and evens you must divide by two?

How can I create an image for the sum of consecutive odd numbers ($1+3+5+...(2n-1)^2 = n^2$)