I would like to add a real example of relevant tensor-product spaces (from quantum theory, but simplified). Maybe it is a bit too complicated, but

for me, it shows the difference between cartesian products and tensor products in the best way!

A long introduction.

We want to work with continuous functions $f, g \in C^0(\mathbb R)$.

You might want to consider those functions to be some probability densities, which say something like "the probability of a quantum particle to be at point $x$ is $f(x)$". (In this example $C^0$ is the 'vector space' and later we will see how $C^0 \otimes C^0$ looks like.)

Now, if $f$ and $g$ are different densities for different systems, say A and B, we might want to ask for the probability of system A to be at state $x$ and system B to be at state $y$ at the same time. This probability will be given as $f(x) \cdot g(y)$.

Now how many different density distributions for (A, B) exist?

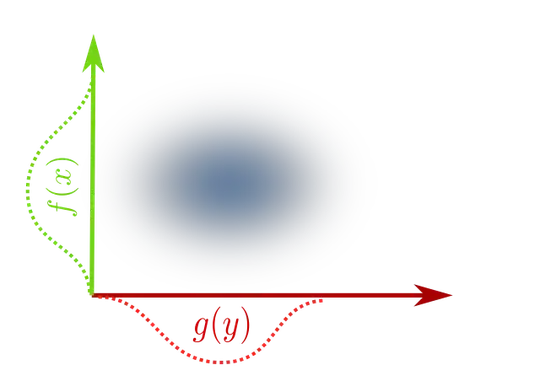

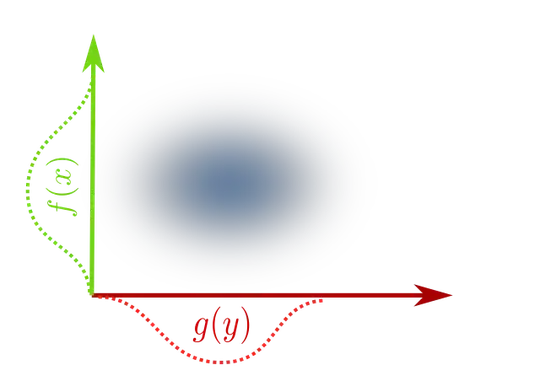

If A and B are independet, then we simply use something like $C^0(\mathbb R) \times C^0(\mathbb R)$ to describe the densities as two splited functions $f, g$. This space would include two-dimensional densities which

are the product $f(x) \cdot g(y)$ of two functions, for example function like in the following picture.

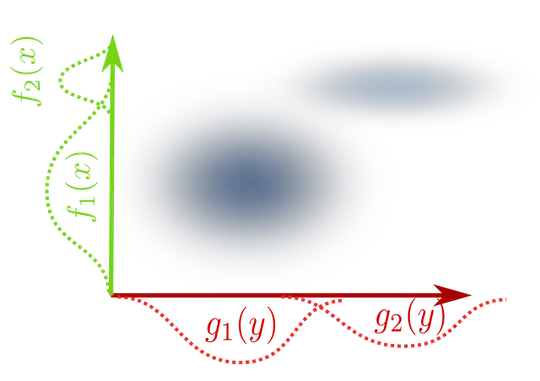

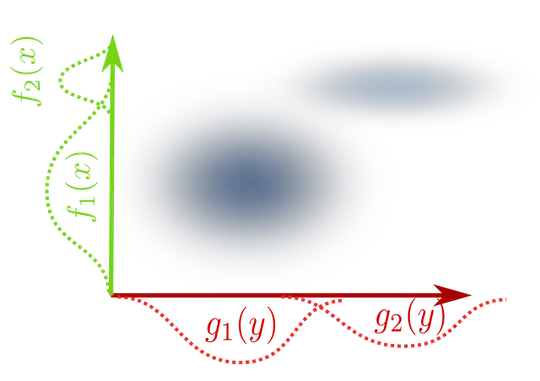

But there are more interesting two-dimensional densities, like this one:

This function is not the product like $f(x) \cdot g(y)$, instead it is more something like $f_1(x) \cdot g_1(y) + f_2(x) \cdot g_2(y) \notin C^0(\mathbb R) \times C^0(\mathbb R)$.

Finally, Tensor-product spaces!

This matches perfectly with the definition of tensor-product spaces:

You take vectors from the individual spaces, (here $f_i, g_j \in C^0(\mathbb R)$)

and you combine them to a new 'abstract' vector $f_i\otimes g_i \in C^0(\mathbb R) \otimes C^0(\mathbb R)$.

In this new abstract tensor-product space, you also can add two pure vectors and get more complicated vectors, for example like in the second plot

$$ f_1 \otimes g_1 + f_2 \otimes g_2 \in C^0(\mathbb R) \otimes C^0(\mathbb R) \approx C^0(\mathbb R^2)$$.

Going further.

This example is kind of trivial and only captures a specific situation. But there are many similar, but non-trivial cases, where interesting spaces can be seen as tensor-product spaces. Applications are plenty and can be found (for example) in differential geometry, numerical analysis, computer graphics, measure theory and functional analysis.

Of course, abstract objects, like the tensor-product, are more complicated and is requires some training to use them in practical situations... Like often in math, there is always a trade-off between learning a general theory and how to apply it to concrete examples versus learning only the tools you really need and risk too learn the same stuff twice in different settings without noticing it. Both approaches are understandable.