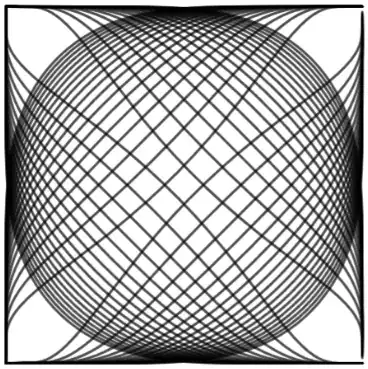

Below is an image of the family of 2D curves for reference. The image is arbitrary. Still trying to formulate a concise question.

I know that the geodesics for flat Euclidean Space are straight lines. But I want to take these curves and try to work backwards to determine the geometry of the manifold that results from these geodesic paths going across it. I can't really visualise the manifold because there's a lot going on. So how would I build up a representation of the manifold that matches up with these curves running across it? What would the steps be to calculate the metric of this space? Is there enough information given by the geodesics to provide a good representation of the manifold? Any other interesting questions you could ask about this graph? What topological information could I learn from these geodesics?

Edit:

If the projection of geodesics from a 2-manifold to the plane were realized below, the 2-manifold would look basically like a 2-sphere right? Does this give any insight as to what the 3-manifold could be?

Edit 2/27/2020:

Partially related: Geometry of transformed spacetimes?, Mapping modular flow to a subspace of $\Bbb R^2.$ Are the same knots produced?, Stability of a combination of two real analytic manifolds.

My desmos code as a more complete version of the diagram below: https://www.desmos.com/calculator/hbiwqpyxzm.

The reason that the posts are related is because the curves below are a symmetrical representations of lines of constant time in a Minkowski diagram mapped via the map $g.$ These curves are not geodesics in Minkowski space. They are hyperbolic curves mapped to the unit square. So hopefully more is clarified than last time I edited this post.

Edit 3/4/2020:

Further clarification:

One could perform revolutions on each "component," of the diagram (below), and then project the "geodesic lines" of some 3-manifold onto this 2-manifold to build up a representation of the 3-manifold. One would have to prove that the lines on the 3-manifold are indeed geodesics.

I feel there needs to be a sort of transitive/sequential map that connects the planar family of 2D curves to a 2-manifold (above it) and a 3-manifold (above that) s.t. the orthographic projection from the 3-manifold yields the 2-manifold and likewise, the orthographic projection of the 2-manifold yields the planar 2D curves.

By a single "component," I mean the space of functions $\ln(x)\ln(y)=s,$ for $\Re(s)>0. $ Note that it is necessary (for my purposes) to only use Euclidean transformations after performing the nonlinear map $g$ described below. First, $g$ acts to "warp" the geometry (needs proof), but gives a way to map this back to the foliation of hyperbolas using a simple change of coordinates. In essence I am, $1)$ warping the geometry and then $2)$ taking a union of these warped components, and next $3)$ configuring them systematically in $(0,1)^2.$ I wish to extend to the case of $(0,1)^3$ but I'm not sure how to do this and what invariants, structural conditions and other conditions I need. Once $(0,1)^3$ is complete, this question should find an answer.

I think it will be helpful and important for others to understand the origin of this question, and the process I took. I first considered rectangular hyperbolas foliating the plane and then mapped the structure via the nonlinear map $g:=(x,y)\mapsto (e^x,e^y).$ Then I took the sub component in $(0,1)^2$ and performed reflections to situate $4$ components in $(0,1)^2.$ The reason for this is to build up a bounded representation of the original foliation of rectangular hyperbolas in $\Bbb R^2.$ (see image above). I would like to consider the boundary of the square to be compact in the topological sense and view the union of the components in $(0,1)^2$ as being bounded by a compact space.