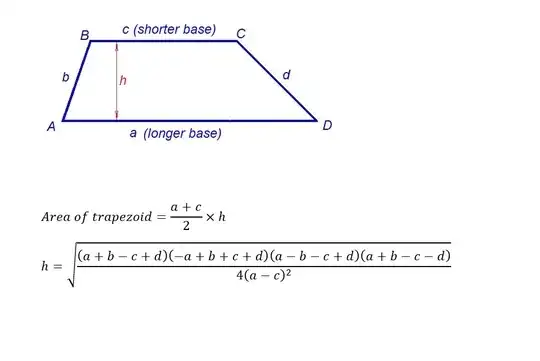

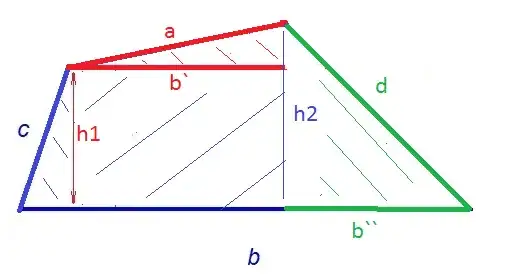

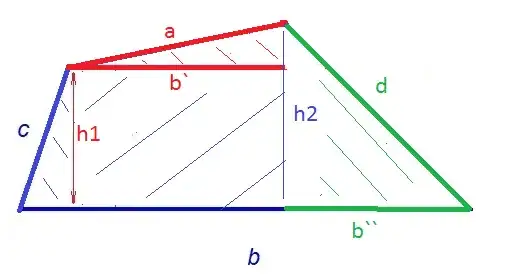

-For the trapzoid abcd to have parallel sides it requires all these conditions to be set for uniqueness of area:

- $a+b+c>d$, $b+a<d$, $c+a<d$.

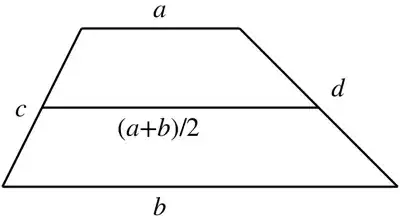

-Neverthless, a trapzoid with non parallel sides can not be defined just by his side lengths, but a fifth coordinate added should.

In this experience we show how come multiple trapzoid shapes can be formed with same lengths of edges.

Imagine we bring a fork and a knife to start dining on some digestable geometrical concepts :

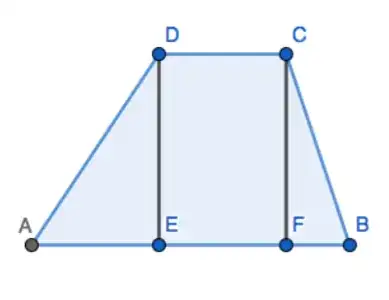

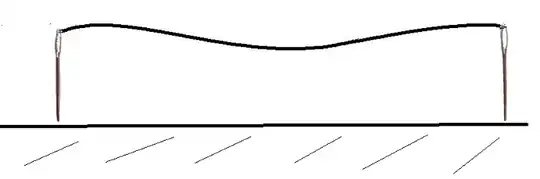

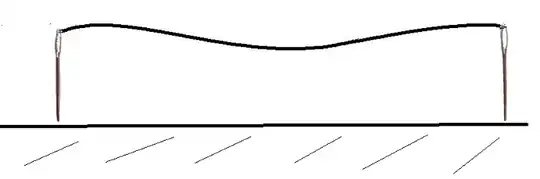

A thread and two pins:

We instill the pins on some flat table:

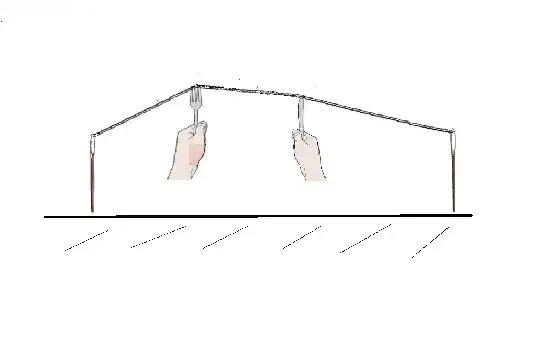

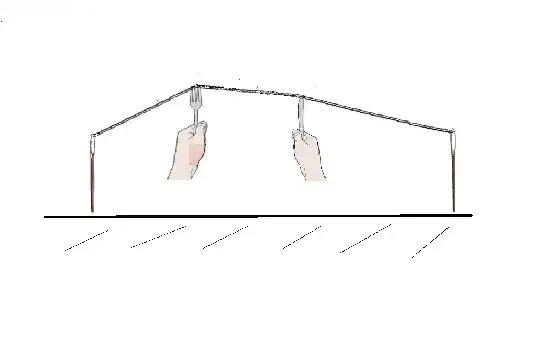

Then take the fork and the knife, choose two fixed points in the string, then pull it from these points with those tools without changing the fulcrum points.

Distance of the chord from the pinpoints to the coordinates of fulcrums dosn't change, while the shape of the trapzoid changes infinitely!

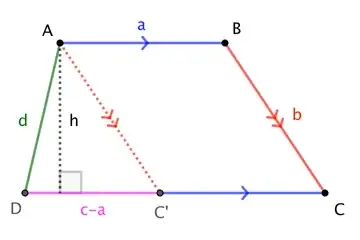

now envisage that $h_1$ is figured by the fork, $h_2$ symbolised by the knife, h1 is directly relative to h2 always regarding the same side lengths. We will show in the following trigonometric relations:

- $\cos\theta=b`/a$,

$sin\theta=(h_2-h_1)/a \implies \sqrt{1-(b`/a)^2}=(h_2-h_1)/a$

- $b``/d= \sqrt{1-(h_2/d)^2}$

- $(b-b`-b``)/c= \sqrt{1-(h_1/c)^2}$

Since there is 4 unknowns $b`,b``,h_1,h_2$ we can formulate $h_1$ in function of $h_2$ and 4 side constants.

Credits for the images goes to canstockphoto.com