Given some definite integral over $[a,b]$ make the substitution $ u = x(x-a-b)$. The integral is then transformed to an integral over $[-ab,-ab]$ which is zero. What is wrong with this reasoning? When can and when can we not make a given u-substitution? Thanks.

-

4If $f(x)$ can be written as $g(x(x-a-b))(2x-a-b)$ for some $g$, then the $\int_a^b f(x),dx$ is, in fact, zero. – Thomas Andrews Aug 03 '17 at 00:34

-

5You can only make the substitution $u=f(x)$ if $f(x)$ is one to one on the given domain of $u,x$. One usually fixes this by splitting the integral: $[a,b]=[a,(a+b)/2]\cup((a+b)/2,b]$, or some variation of this. – Simply Beautiful Art Aug 03 '17 at 00:36

-

I'm talking about in general u-subsitutions? There are many more examples where the integral is "zero" when making a certain u-substituion. – mtheorylord Aug 03 '17 at 00:36

-

3@SimplyBeautifulArt Not exactly. We don't need 1-1, we just need the end points to match up. – zhw. Aug 03 '17 at 00:38

-

No, as you've noted $h(x)=x(x-a-b)$ takes values $-ab$ at bot ends, and, in general, $h(x)=h(a+b-x)$. – Thomas Andrews Aug 03 '17 at 00:39

-

@mtheorylord Clearly it is not one to one on the domain, as you have shown that $a(a-a-b)=b(b-a-b)$. – Simply Beautiful Art Aug 03 '17 at 00:39

-

@zhw. Sorry, my brains not working for some reason. Could you expand on that? – Simply Beautiful Art Aug 03 '17 at 00:40

-

$x\mapsto u (x) $ is not bijective. – hamam_Abdallah Aug 03 '17 at 00:41

-

4@SimplyBeautifulArt If $f$ is continuous on $[a,b]$ and $g:[c,d]\to [a,b]$ is $C^1$ with $g(c) = a, g(d)=b,$ then $\int_a^b f(x),dx = \int_a^bf(g(t)),g'(t),dt.$ – zhw. Aug 03 '17 at 00:54

-

https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/829939/why-does-this-u-substitution-zero-out-my-integral is a specific example of this question for the case $a=0, b=2.$ – David K Aug 03 '17 at 01:04

-

@SimplyBeautifulArt Typo, the second integral is over $[c,d].$ – zhw. Aug 03 '17 at 01:05

-

@zhw. Mmm, okay. – Simply Beautiful Art Aug 03 '17 at 01:37

-

Possible duplicate of Why does this $u$-substitution zero out my integral? – wchargin Oct 22 '17 at 21:57

3 Answers

In integration theory when you want to use a u-subsitution you have to use a function which is a $C^1$-diffeomorphism. Otherwise you could end up with funny things.

Edit Actually a diffeomorphism is not necessary as pointed out by @zhw. To apply the substitution $x=\psi(u)$ from $u \in [c,d]$ to $x \in [a,b]$ you "only" need to have $\psi$ to be $C^1$ and $\psi([c,d])$ included in the domain of $f$, with $\psi(c)=a$ and $\psi(d)=b$.

For example if you want to compute $\int_{-1}^1 x^2\mathrm{d}x$, using a u-substitution $u=x^2$ will change the bounds to $1$ and $1$ and give 0, which is not true. This is because the function $x \in [-1,1] \mapsto x^2$ is not a bijection.

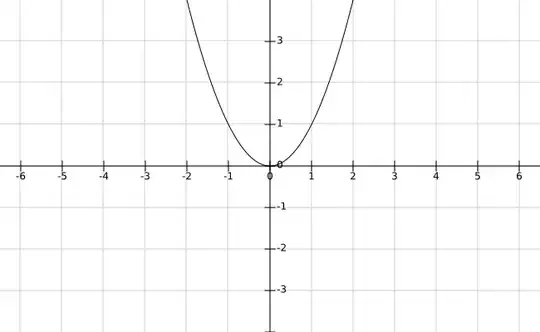

In your case your function $x \in [a, b] \mapsto x(x-a-b)$ has the following graph for $a=-1$ and $b=1$. You clearly see that this function is not 1-1.

The fact that your substitution is not 1-1 is clearly due to the square. Let $\phi: x \in [a,b] \mapsto x(x-a-b)$. The function $\phi$ reaches its minimum in $c=(a+b)/2$ and is bijective on $[a, c]$ and on $[c, b]$. If you split your integral into 2 integrals on these intervals you can use your substitution.

You would get $\int_a^b f(x) \mathrm{d}x=\int_a^c f(x)\mathrm{d}x + \int_b^c f(x)\mathrm{d}x$

Now use $u=\phi(x)=x(x-a-b)$. You have therefore $x=\dfrac{a+b-\sqrt{(a+b)^2+4u}}{2}=\psi_1(u)$ on $[a,c]$ and $x=\dfrac{a+b+\sqrt{(a+b)^2+4u}}{2}=\psi_2(u)$ on $[c,b]$

This would give $$\int_a^b f(x) \mathrm{d}x=\int_{-ab}^{-(a+b)^2/4}f(\psi_1(u))\psi_1'(u)\mathrm{d}u + \int_{(a+b)^2/4}^{-ab}f(\psi_2(u))\psi_2'(u)\mathrm{d}u$$

And you see that you cannot "merge" these two integrals because their content is now different.

Of course this u-substitution does not seem to help a lot to compute the integral, particularly because $f$ is general. But if $f$ has a particular form, maybe this could help.

- 4,290

- 15

- 23

-

If you try $u=x^2$, the real problem is that $x^2,dx = \pm 2\sqrt{u},du$. That $\pm$ is the key to the problem. – Thomas Andrews Aug 03 '17 at 00:41

-

Or this is where you should break it up into $[-1,0]$ and $[0,1]$, intervals that are bijective. – Simply Beautiful Art Aug 03 '17 at 00:43

-

Aherm, why not use $a=-1$ and $b=1$ to match up with your example? – Simply Beautiful Art Aug 03 '17 at 00:46

-

@ThomasAndrews yes the $\pm$ is essentially due to the fact that the square function is not bijective – fonfonx Aug 03 '17 at 00:47

-

@SimplyBeautifulArt yes I wanted to elaborate on your first point in an edit. And you are perfectly true for your second comment, thanks I edited – fonfonx Aug 03 '17 at 00:49

-

2You don't need a diffeomorphism, you just need the end points to match up. See my comment above. – zhw. Aug 03 '17 at 00:57

-

1You don' need $C^{1}$ either. $\psi'$ just needs to be Riemann integrable. – MathematicsStudent1122 Aug 03 '17 at 01:45

The only way you could do such a substitution to compute $\int_a^b f(x)\,dx$ is if there is some function $g$ such that: $$f(x)\,dx=g(u)\,du=g(x(x-a-b))(2x-a-b)\,dx$$

So if $f(x)=g(x(x-a-b))(2x-a-b)$, then let $h(x)=f\left(\frac{a+b}{2}+x\right)$, then $h$ is defined on $\left[-\frac{b-a}{2},\frac{b-a}{2}\right]$, and $h(-x)=-h(x)$. So you get that if $f(x)$ is of this form, then:

$$\int_{a}^{b} f(x)\,dx \int_{-\frac{b-a}{2}}^{\frac{b-a}{2}}h(t)\,dt= 0$$ since $h$ is an odd function.

So when the substitution can be done, you do get $0$. The problem is that, for the general function $f$, you can't find a function $g$ - you end up, instead, with a multi-valued function $g$.

Similarly, if you use $u=\sin x$, to calculate $\int_{0}^{\pi} f(x)\,dx$ then there should be a $g$ such that $f(x)=g(\sin x)\cos x$. And you can show that $$\int_{0}^{\pi}g(\sin x)\cos x\,dx = 0.$$ This is because $f(\pi-x)=-f(x)$.

More generally, if $g(x)$ is a continuous function and $u(x)$ a differentiable function and $u(a)=u(b)$ then any: $$\int_{a}^{b} g(u(x))u'(x)\,dx = 0$$

Proof: Let $G(x)=\int_{a}^{x} g(t)\,dt$. Then $g(u(x))u'(x)=\frac{d}{dx}(G(u(x))$ by the chain rule and the property that $G'=g$. So, by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, $$\int_{a}^{b} g(u(x))u'(x)\,dx = G(u(x))\big\vert_{a}^{b}=0$$

This is essentially the long form of substitution - substitution is doing the reverse of the chain rule.

- 186,215

If I use this example : $\displaystyle \int_{-1}^1x^2\cdot dx$

And let

$$\boxed{\begin{array}{ll}f:&\mathbb{R}_+&\to \mathbb{R}\\&X&\to\sqrt{\dfrac{X}{4}}\end{array}\qquad \text{AND }\qquad \begin{array}{ll}\varphi:&\mathbb{R}&\to \mathbb{R}_+\\&x&\to x^2\end{array}}$$

$f$ is continuous and $\varphi([-1,1])\subset \mathcal{D}_f=\mathbb{R}_+$ which are sufficient

$\begin{array}{ll}\displaystyle \int_{-1}^1x^2\cdot dx &=\displaystyle\int_{-1}^1 \sqrt{\dfrac{x^2}{4}}\cdot2|x|\cdot dx=\displaystyle\int_{-1}^1 f(\varphi(x))\;|\varphi'(x)|\cdot dx\\\\ &=\displaystyle\int_{-1}^0 \sqrt{\dfrac{x^2}{4}}\cdot2(-x)\cdot dx+\displaystyle\int_{0}^1 \sqrt{\dfrac{x^2}{4}}\cdot2x\cdot dx\\\\ &=\displaystyle\int_{0}^{-1} \sqrt{\dfrac{x^2}{4}}\cdot2x\cdot dx+\displaystyle\int_{0}^1 \sqrt{\dfrac{x^2}{4}}\cdot2x\cdot dx\qquad \textbf{We apply the substitution: }s=\varphi(x)\\\\ &=\displaystyle \int_{\varphi(0)}^{\varphi(-1)}f(s)\cdot ds \quad +\int_{\varphi(0)}^{\varphi(1)}f(s)\cdot ds =2\int_0^1\dfrac{\sqrt{s}}{2}\cdot ds =\dfrac{2}{3}\end{array}$

So $\varphi$ doesn't need to be a bijection

- 1,750