I've been reading articles on pseudo-randomness in computing when generating a random value. They all state that the generated numbers are pseudo-random because we know all the factors that influence the outcome, and that the roll of a die is considered truly random. But I'm wondering why. Don't we know all the physical forces that influence the die when it's being rolled? Or is there too many of them?

-

14Can you accurately predict every single nerve pulse running to the muscles controlling the hand that rolls the die? – celtschk May 20 '17 at 09:45

-

2@celtschk This video of Persi Diaconis is about coin flips, but it's interesting nonetheless. – Fabio Somenzi May 20 '17 at 13:54

-

You might want to read What We Cannot Know by Marcus de Sautoy. It covers a lot of this ground. – David Richerby May 20 '17 at 21:25

-

3"It is shown that for the realistic values of the initial energy the probabilities of the die landing on the face which is the lowest one at the beginning is larger than the probabilities of landing on any other face. [...] In real experiment, the predictability is possible only for very small \epsilon, i.e., an accuracy which in practice is extremely difficult to implement[...]" -- The three-dimensional dynamics of the die throw, Kapitaniak, Strzalko, Grabski, Kapitaniak. – Jeffrey Bosboom May 20 '17 at 22:08

-

5To go with all the great answers here, I'd like to point out your own phrasing, "... the roll of a die is considered truly random." Whether or not there is anything truly described as random in this universe is actually a philosophy question. However, as many have pointed out, the die is "close enough" to random to earn a particular level of fame. – Cort Ammon May 20 '17 at 22:19

-

7So many awful answers upvoted to the top. Guys, not every instance of the "random"ness you see in your daily life is an example of chaos or quantum theory. Use your common sense, people. – user541686 May 20 '17 at 23:03

-

3@Mehrdad Do you deny that extremely similar initial conditions for a die throw will lead to very different results? – lesath82 May 21 '17 at 00:16

-

2@lesath82: With a degree in physics I think you know (or should know) exactly what I am/am not saying. I'm not going to waste time mincing words. – user541686 May 21 '17 at 00:31

-

6No @Mehrdad , I don't get your point, and I don't think yours is a productive attitude. The millisec digit of a chronometer stopped without looking is randomness without chaos. To me, the bounces of a die are chaotic. – lesath82 May 21 '17 at 07:42

-

This question is effectively equivalent to: "what does it mean to be random?" There are many answers, some complicated, some simple. What I'll say is that: if you were able to predict the outcome perfectly, then we wouldn't call it random. You could likely create a machine that rolled a die in a controlled manner in such a way to enable predicting the outcome accurately. It comes down to the issue of predictability. – jdods May 23 '17 at 19:25

-

"Don't we know all the physical forces that influence the die when it's being rolled?": no that would require a highly sophisticated equipment to capture this information (which does not exist AFAIK) and even super accuracy in the measurements would not allow to predict the motion past one or two bumps. – May 25 '17 at 19:15

15 Answers

A die roll is only considered random if the external factors are not controlled.

Practiced dice cheats can roll numbers they want to roll. So talk about nerves and blood vessels and quantum effects are just wrong. These cheats control the meaningful factors such that they influence the outcome of the roll, predictably. Even if someone only increases their chance of rolling a certain number by a few percentage points, that's huge in gambling terms.

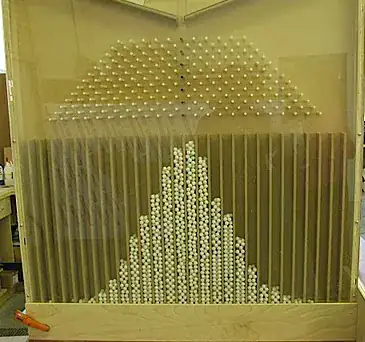

That's why there are rules on how the dice must be rolled at casinos, and inventions such as the dice tower:

- 455

-

5

-

7@NickT One of those devices might be more portable than the other... – Tony Ennis May 21 '17 at 11:56

-

Even if the external factors are largely controlled, it is still random. This seems to be missing from many answers here: random does not necessarily mean uniform random, and a biased die throw is still random. For PRNG's however all external factors are controlled, and there is no entropy at all. – TMM May 22 '17 at 18:41

-

1The die that came through the tower are obviously NOT random. All three are powers of a prime! AND are also Fibonacci numbers! – richard1941 May 23 '17 at 18:28

-

Also, the sum of the three die is a power of a prime AND a Fibonacci number! The tower merely requires greater skill from the cheater; it does not stop her from cheating. – richard1941 May 23 '17 at 18:36

This has to do with chaos theory: the tiniest variation of the initial conditions will cause an enormously different output. For a physical system like a die toss:

even from a classical point of view, it is very unlikely that you can know the very exact initial conditions of the throw. And of the environment: the "floor" distance and surface characteristics (think of the abrupt effect of each bounce, that will be very different depending on the most infinitesimal variation of the impact parameters), the air conditions (thermodynamic and kinematic)...!

this becomes actually impossible if you include the uncertainty principle (that prevents you from knowing the exact value of certain pairs of variables at the same time, e.g. position and momentum, but see below);

it would be impossible from a practical point of view to propagate these initial conditions without introducing round-off errors, that due to the chaotic nature of the problem would make the result completely unreliable;

even if you could perform exact calculations, there is still the quantum indeterminacy (again, see below) that affects the development of the status of the die: at each bounce, even when air molecules brake the die rotation, it is impossible even theoretically to predict what will happen in the next instant with absolute certainty.

As pointed out in many comments and with many downvotes, the contributions to the randomness of the roll from quantum effects are insignificant from any practical point of view. Nevertheless I do want to mention them since they provide a theoretical watertight border against a deterministic idea of the phenomenon.

Taking care of another possible correct objection, I have to underline that my answer holds for a fair throw. If you think of a die "tossed" from, say, $1\,\mathrm{mm}$ above a horizontal flat floor, with negligible initial velocity and a face parallel to the ground, it is obvious that you can predict the outcome with practical certainty. Moving progressively away from this limit situation, you have many halfway toss styles that can influence the probability distribution of the outcomes, if only by a few percent. I'm referring to the opposite limit, when the system can be considered ergodic. When I heard this term applied to the die, maybe not $100\%$ properly, it was with the meaning that the system "scans" over time all the possible outcomes many many times, with equal probability and with no recognizable pattern. Add the fact that a fair throw starts with a random grip of the die, and you really have equal chances for all the outcomes.

- 2,605

-

38

-

-

6You can say they should be negligible, since the average of an enormous amount of probabilistic microscopic effects usually leads to a predictable macroscopic outcome. But it is never going to be exact in a mathematical sense – lesath82 May 20 '17 at 12:54

-

17

-

Just because something is not known (or cannot be known), does not mean it is not existing. So the uncertainty principle does not matter in principle, when discussing if something is truly random. However, since this is about pseudo random numbers, I think the idea is "what do we know" anyway and therefore the point about uncertainty principle seems valid. – Zelphir Kaltstahl May 20 '17 at 14:28

-

1@MattSamuel What do you think where the "border" between too small and not too small is then? Is goes against logic that some smaller action has no influence, because it is smaller. We might say "We don't know how it influences the bigger picture.", but surely the influence is not mathematically equal to zero. It might even be the case, that quantum effects balance themselves and the outcome will be the same in the end, but that only means that two or more actions went in "different directions" and therefore did indeed influence the outcome. Think some of them gone and might have imbalance. – Zelphir Kaltstahl May 20 '17 at 14:32

-

18@Zelphir Technically it's not equal to $0$, but with the exact same initial forces the outcome will be the same to many many decimal places. Minuscule doesn't even begin to describe the influence of quantum effects on something that big. – Matt Samuel May 20 '17 at 14:36

-

3This answer needs a tl;dr saying that we call it random because with current technology it is not humanly possible to predict the outcome of any given roll even if we know the outcome of all past rolls. – Readin May 20 '17 at 19:43

-

1@Zelphir The uncertainty principle says that you can't know the initial conditions. Even microscopic changes to the initial conditions have macroscopic effects on the outcome, which means that you can't predict the outcome. – David Richerby May 20 '17 at 21:30

-

2@Readin No it doesn't, because that's not what the answer says. The limits come from physics, not technology. – David Richerby May 20 '17 at 21:30

-

-

2@MattSamuel: Quantum effects can and do come into effect in macroscopic systems - at least theoretically - provided there is a some exponentiation (such as collisions around a curved surface affecting angle of rebound, which you can reasonably expect on a bouncing die). There is a paper about this using elastic collisions between billiard balls showing that uncertainty at quantum level can be such that after ~11 collisions, there is a huge uncertainty in direction of travel at the last stage. Sorry I cannot find a free version: http://aapt.scitation.org/doi/10.1119/1.1973895 – Neil Slater May 21 '17 at 18:19

-

1@NeilSlater: You realize that paper is for perfect spheres/tables undergoing perfectly elastic collisions, right? In that case, of course you will have arbitrarily large error given a long enough amount of time, and of course with exponential growth the timespan won't be that long. Hell, a perfectly elastic object won't even stop for you to ask about its final orientation in the first place. But so what? With imperfect objects and inelastic collisions, many, many small uncertainties get suppressed far faster than they can grow, and the cubic shape only makes that easier/more likely. – user541686 May 22 '17 at 02:59

-

1@Mehrdad: Yes I do realise that. The balls are not modelled as collections of atoms either. It is just a thought experiment. Your other assertions seem off to me, and I disagree - I could counter them, but perhaps rather than argue them out here raise a question on the physics stack exchange? – Neil Slater May 22 '17 at 07:02

-

@NeilSlater You realize that dice are immersed in a huge source of thermal noise which destroys all quantum coherence? Not speaking about turbulence in the air which is on much larger scale than the quantum fluctuations or Brownian motion (and that will appear even in perfectly still air due to flow around the dice). – Vladimir F Героям слава May 22 '17 at 13:14

-

The uncertainty principle is grossly misused here. For macroscopic elements ( ~ anything bigger than a hydrogen nucleus), its effects are infinitesimal and can be safely ignored, because the error margin of any measurement for macroscopic dimensions are orders of magnitude bigger than it. – Mindwin Remember Monica May 22 '17 at 13:58

-

Ok people; I have rephrased my explanation about the inclusion of quantum effects, I hope this is acceptable now – lesath82 May 22 '17 at 14:45

-

@VladimirF: Yes I realise that. The exponentiation factor is large, because it is magnified by travel distance between collisions, and this does not require coherence or continued uncertainty in momentum vs position. The effect happens even classically (assuming there is some initial error or uncertainty) - there is no reason not to extend the initial measurement accuracy requirements into distances that would be affected by quantum uncertainty (even for macro sized objects). What is surprising is with a very simple setup how few collisions bring the magnification of effects into that realm. – Neil Slater May 22 '17 at 15:07

-

In addition, for the quantum uncertainty to not be swamped by other larger effects that would cause uncertainty, then a process needs to behave chaotically. A chaotic system will mix combinations of effects that are at completely different magnitudes and essentially make them equally important to the measured outcome (unless any one effect drives the system out of chaotic range). – Neil Slater May 22 '17 at 15:54

-

1@MattSamuel and others: I disagree. The chaotic systems introduce a gain which grows exponentially and becomes huge, making any perturbation significant (for instance, 80 doublings make you reach the Avogrado number). Of course all sources of perturbations add up, making them impossible to separate. But the "classical" perturbations are deterministic and can (at least in a thought experiment) be repeated. By contrast, the quantum perturbations are believed to be undeterministic, and in theory a better source of randomness. – May 26 '17 at 12:50

The roll of a die is modelled as being random.

The purpose of a mathematical model is to help us to understand some feature of the world.

A real die falling onto a surface is a mechanical system. It can be modelled by a deterministic mechanical model, which could be used to generate pseudorandom numbers. However, this is not usually a particularly useful model. Instead we can use a uniform discrete distribution as a model for the die. This is a much better model. It simplifies the mechanical system, and allows you to gain insight into the world. It allows you to consider the expected value and variance of the die roll (these concepts would be hidden by the detail of the mechanical model).

In mathematical questions phrases like "Yusuf rolls a fair die..." are part of the code: It means "There is a random variable with a discrete uniform distribution on {1...6}. The question is asking you to form a mathematical model. A more sophisticated model takes into account the slight biases due to the mass of the die not being centred, or the sides not being identical.

This is what is meant by a die being random: It is an object that is usefully modelled by a random variable.

- 1,390

-

Note that "randomness" does not require a discrete uniform distribution. Yusuf and his die could be random, but biased. So, how do you test Yusuf and his die for randomness, if they might be biased but still random? – richard1941 May 29 '17 at 16:45

I feel the existing answers all concentrate on the dice and would like to offer another perspective, concerned with the generator:

The "pseudo" in "pseudo random generator" means that the next value is completely determined. There is no surprise at all, no matter what you do. The only "surprise factor" arises if you do not happen to know the internal state of the generator. But it is trivially easy to get the internal state (just read out the RAM), and it is there.

Also, if you restore a known internal state, you can repeat the series of "random" values you got before. This is actually, where PRNGs are used, often a welcome feature - for example, you can generate a lot of, well, pseudorandom data from a very small seed value. So to communicate whatever you generated, you only need to transfer the seed, not all values. Or you can test something which needs seemingly random input in a repeatable way (for debugging, demonstration etc.).

For dice, or many other physical processes, the problem is not so much that we are too stupid to read out the state, but that there actually is no deterministic process underlying whatever we are using to generate the next random value. It is not so much about us not being able to figure it out ("read the RAM") but that there "is no RAM". For dice, the previous roll of the dice has no relation whatsoever to the next roll. Sure, we might, in ideal conditions and with stunning advances in measuring apparatuses, somehow try to predict the current roll while it is happening. But even if we'd manage to do that (quantum effects, Heisenberg, chaotic effects ignored), this roll would have no relation whatsoever with the next roll. Hence we call it truly (independently) random.

If you are more interested, a nice read is "The Art of Computer Programming" by Knuth. He spends a lot of time on PRNGs, including how to measure how "random" a random generator actually is.

- 838

-

My pennyworth: a "random" sequence is often confused with "equal distribution". If that were so, gamblers could look at the history and say "a 6 is due" but as you say, that is a false hope. People often evaluate a PRNG by its statistical results, because practically they do want a "random but uniform distribution", and not "random" which can be anything. Also, I am suprised nobody has yet mentioned the butterfly effect. – Weather Vane May 20 '17 at 19:28

-

-

@Weather The butterfly effect is the first example in wikipedia's entry about chaos theory. In some sense, it has been mentioned – lesath82 May 20 '17 at 21:57

-

1Much better description of psudorandom vs really random than the other answers – Sir Adelaide May 22 '17 at 01:43

-

4@WeatherVane The "random" distribution of an ideal six-sided die is an equal distribution. The gambler's fallacy is the idea that the "equal distribution" can ever tell us that "a 6 is due." – David K May 22 '17 at 13:46

-

2To expand on the point about the pseudorandom seed, you can use this feature to debug a "random" algorithm implemented in a computer. With a truly random generator you would not be able to reliably reproduce the circumstances that led to observing the bug. – David K May 22 '17 at 13:50

-

-

@DavidK no, if I throw a perfect die 6 times it is very likely I will not get one of each face. If I throw it 6000 times it is quite likely I will not get 1000 of each. The "equal distribution" is a statistician's device, with a probability attached for whether the ideal result will be achieved. – Weather Vane May 22 '17 at 17:16

-

... it is quite possible for a perfect die to roll the sequence 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1 ... etc, but that sequence will not happen very often. – Weather Vane May 22 '17 at 17:26

-

3@WeatherVane In this context "equal distribution" means what the statistician says it means. If you try to use it with a different meaning in a mathematical discussion, you will cause a lot of confusion and pointless arguments. You're in the middle of such a pointless argument right now, in fact. – David K May 22 '17 at 17:27

-

@DavidK in that case I don't know why you called my first comment, only to repeat my point, seeing you were the one to promote the pointless arguement. – Weather Vane May 22 '17 at 17:29

-

@WeatherVane You said a "random" sequence is often confused with "equal distribution," and gave the gambler's fallacy as evidence. The gambler's fallacy is a fallacy not because it assumes equal distribution when outcomes are not equally distributed, but because it is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of what "equal distribution" means. I think your comment actually promoted such a misunderstanding by suggesting that if a random variable could have an equal distribution, the gambler's fallacy would be true. That's why I objected. – David K May 22 '17 at 17:46

-

@DavidK you are twisting it. What statisticians say is a prediction of the real die, which is approximately true. Programmers expect a PRNG to conform to that. Isn't the question inviting such discussion? I thought AnoE's answer a good one. At a tangent, I showed a friend my "lucky dip" lottery ticket with numbers like 2, 17, 18, 19, 25, 28 who said "that does not look very random to me" and my reply was "random does not mean evenly distributed" and it doesn't. Only over a large number of iterations does that happen to be true. Statistics do not control nature, they observe and predict. – Weather Vane May 22 '17 at 18:03

Even without invoking Quantum Theory, some systems are chaotic. In principle, they can be predicted but this requires impossibly perfect measurements of the initial state. Quantum theory prohibits these perfect measurements but such precision would be required that even without quantum mechanics, sufficiently perfect measurements would not be possible.

One nice example is a toy which is a consists of a pendulum which contains a magnet over a base with two magnets; the magnets are aligned to attract the pendulum. Place the base magnets slightly either side of the rest point of the pendulum. Move the pendulum off centre and release it. It will come to rest over one of the magnets but which? There will be areas around each base magnet in which the pendulum will predictably stop over that magnet. However, outside those areas, the behaviour is very complex. Here is one of the first hits that I found in a search, I expect that there are better ones: A pendulum and two magnets - an example of a chaotic system.

A purer mathematical example is the Mandelbrot set. In principle it is utterly predictable. Any point is either in the set or not. However, in some areas, this cannot be determined in finite number of steps. Mandelbrot set at Wikipedia

Another example is the solar system. Assume that Newton was right and ignore everything except the Sun and major planets (include Pluto if you wish). With a perfect measurement of the initial state and perfect calculations, we could predict its future indefinitely into the future. However, the tiniest error could render the results seriously wrong later on.

- 8,854

-

7I think the Mandelbrot set is a bit of a "bad" example. Just like PRNGs it "looks" random but is completely deterministic. Saying that it is "too complicated to predict" is not really a good measure - if I just give you the output of a PRNG you may also have a hard time predicting the next output, which does not mean it is truly random. – TMM May 20 '17 at 09:10

-

2@TMM Actually, that was the point of the example. Even in the predictable world of pure mathematics, it is only predictable in an idealistic Platonic sense. Which is more surprising: that the Newtonian Solar System is predictable in principle but not in practice or that the Mandelbrot isn't practically predictable either? My message is that, in the real world, we have to live with unpredictability. You could say that randomness is just ignorance or the inability to calculate well enough. My examples are intended to show that randomness isn't going away. – badjohn May 20 '17 at 09:24

-

The Lorenz example is one of the simpler systems that exhibit exquisite sensitivity to initial conditions. – J. M. ain't a mathematician May 20 '17 at 14:35

-

@badjohn I understand that some randomness concepts are debatable, but it might not be wise to stray from standard definitions for these questions. I could also argue that the program "print 1" is a true RNG, where the randomness comes from the random physical behavior of the processor, where say once in a blue moon the processor outputs 0 due to some internal screw-up. After all, there are no requirements on RNGs that the output is uniform; any non-zero entropy generator qualifies. (But when explaining PRNG vs RNG I would not use that as an example.) – TMM May 20 '17 at 22:30

-

@TMM My only point here is that to get unpredictable behaviour, you don't have to leave mathematics. Is there a standard definition randomness? Possibly in Computer Science but this is a Mathematics group. For example, Wolfram MathWorld is fairly vaguely on the subject. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Random.html – badjohn May 21 '17 at 08:26

-

@badjohn The question was mostly on the difference between pseudo-randomness and randomness that is not pseudo-random, a difference which is pretty well-defined, also in mathematics. – TMM May 21 '17 at 14:54

-

@TMM Sorry, I see that you did not introduce the computing element. Still, there is relevance to my comments. The OP asked whether there are too many physical forces; my point is that there can be uncertainty for even more basic reasons. – badjohn May 21 '17 at 15:33

Don't we know all the physical forces that influence the die when it's being rolled?

Yes. But, when throwing a die in a normal way, we aren't able to control the initial conditions (i.e. the position where you throw the die, and the applied force) and other conditions which might affect the throw (e.g. air currents).

Even when you just 'drop' a die from a certain height, you'll see the outcomes are random. That is, until you reduce the height to a fraction of the size of the die; then the forces are small enough to be able to predict the outcome of the 'throw'.

- 4,000

-

8"you'll see the outcomes are random" - How do you "see" that an experiment produces truly random rather than pseudo-random results? – TMM May 20 '17 at 08:46

Think of a Galton board.

Even though all balls are dropped the same way, the outcomes of the collisions are completely unpredictable.

The device will be influenced by a person caughing in the next room. The same goes with dice.

-

-

I do struggle with 'completely unpredictable'. I mean, given the Galton board (demonstrating binomial distribution with parameters ( p , n ) - I'm pretty sure that I can accurately predict that any ball will fall somewhere within 0,n... Just the same, when rolling a normal d6, we can accurately predict that the dice will not roll a 0 or a 7. – Konchog Jun 18 '22 at 11:33

We argue using simple models that all successful practical uses of probabilities originate in quantum fluctuations in the microscopic physical world around us, often propagated to macroscopic scales. Thus we claim there is no physically verified fully classical theory of probability. We comment on the general implications of this view, and specifically question the application of classical probability theory to cosmology in cases where key questions are known to have no quantum answer. We argue that the ideas developed here may offer a way out of the notorious measure problems of eternal inflation.

So, whenever something is truly random, the probabilistic aspects of it will always derive from quantum mechanical processes. In the article it's explained how quantum processes in the brain propagate via our nerves to our hands when we throw coins or throw dice. And this is true even if you consider betting on the value of the digits of $\pi$. The probability that the $123543745345385$th binary digit of $\pi$ is 0 seems to be a purely classical probability, but in the article it's pointed out that even this probability has a purely quantum mechanical origin.

- 10,716

We assume randomness when identical inputs to a system give rise to different outputs. For a die roll, we are not able to consistently describe the changes to the system from roll to roll, for as you've supposed there are too many factors (and see Chaos Theory). So while a phenomenon may in principle be best modelled deterministically, it's often more practical and "good enough" to use a random model instead.

- 913

There are no such things as "truly random" and "pseudorandom", at least in science.

An event is random if you do not have enough information to determine its outcome. Randomness depends on your state of information. This includes that an event may be random for you, but not somebody else (who has more knowledge).

For an outsider, who cannot see the internal state of a computer, the sequence generated by that computer may be random because he/she has not enough information to determine the next number. For the computer admin, the sequence is not random.

Some events (e.g. in quantum states) may be "truly random" in the sense that it is impossible to gather enough information to predict them. But this is a purely philosophical question and nobody can say whether some clever physicist will be able to predict quantum states in the future.

- 530

-

Einstein was a defender of the theory of hidden variables, i.e. the idea that there is anyway some determinism to which we don't have access. But the experiment of Alan Aspect seems to have refuted it. – Jul 18 '18 at 21:21

-

AFAIK, Alain Aspect investigated local hidden variables. I do not see how hidden variables in general could be ruled out. – J Fabian Meier Jul 19 '18 at 06:25

The existence of true randomness is a philosophical question. However, many completely deterministic processes approximate the statistical properties of randomness. This is how we develop and test pseudo-random number generators, which are completely deterministic processes that nonetheless are statistically indistinguishable from a truly random process.

Therefore, one good operational definition of a random process is that it passes the same tests that pseudo-random number generators must pass (suitably adjusted for whatever non-uniformity we are assuming about the process).

So, we consider a die roll to be statistically random insofar as it satisfies the requirements we would place on an equivalent pseudorandom number generator.

As an example, one such requirement is the absence of any statistically significant autocorrelation between successive rolls (up to some large number of lags). Technically, all pseudorandom number generators will fail this test for a sufficiently large lag (very, very large), where the autocorrelation will spike to 1.0.

However, for smaller lags, it will behave statistically like it came from a process that can generate any value in its range for any given trial.

-

Tell me more.... I am interested in how to test for randomness, when the underlying distribution is unknown. What about "spurious correlations"? – richard1941 May 29 '17 at 17:00

If we know the algorithm of a pseudo-random number generator, and we know its current internal state, then we can predict with certainty the next number.

But with a die roll, although we might be able to predict with some level of accuracy what the number might be, it depends on how much we know about factors such as:

- the starting position and orientation of the die

- how it is picked up and thrown

- the motion and density of the air it passes through

- the surface it lands on, particularly at the points where it will probably land/bounce

If we collude with the roller and have them "roll" it by placing it on the surface with a given number facing upwards - effectively controlling point 2 above - then we can even predict, with great surety, what the outcome will be.

Therefore we must make some additional assumptions about our level of knowledge/control in order to consider a die roll to be random.

Informally, I'd say that we would tend to assume:

- only vague knowledge of a die's position and orientation (maybe just which number is facing up)

- no knowledge of how it will be picked up and thrown

At this point, I would expect any outcome to be possible (even if the air and surface were the same each time). So with just those two assumptions, I would informally consider the outcome of a die roll to be "random".

- 161

I think the die is random because it BEHAVES AS IF it is random. Likewise, the pseudorandom generators in computers. The difference is that in the computer, you can reset the generator and get the exact same sequence; nobody I know has been able to do this with dice.

I heard of a long ago Soviet computer that had an actual random digit generator. I don't know if they used thermal noise or a radioactive decay detector, but it was abandoned because there was no way to repeat the exact same sequence when software was being debugged.

- 1,051

-

Since 2013, the Intel processors (Ivy Bridge microarchitecture) feature a built-in hardware truly random number generator that exploits thermal noise. – May 25 '17 at 21:37

-

Thanks for that! Intel does a pretty good job of keeping the insides of our processors secret from us. Not like the old days of the 8080, when we knew all of the registers and could program them in machine language. – richard1941 May 29 '17 at 16:57

-

1I doubt the it was kept secret. As such a device is very handy in cryptographic applications (for which it was explicitly designed), they must have heaviliy advertized it at the time. http://spectrum.ieee.org/computing/hardware/behind-intels-new-randomnumber-generator – May 29 '17 at 17:31

A die behaves randomly because it forms a chaotic system, that has an extreme sensitivity to the initial conditions. In other words, assuming you are able to throw the same die in the exact same conditions, but after is has lost a single atom, it can end-up on another face. Really.

And in fact, throwing in the exact same conditions is impossible because we can't control the state of a billion billion atoms simultaneously, which fluctuates in an extremely complex way due to thermal motion.

No computer on Earth could simulate the trajectory with enough accuracy.

A die can land on (finally)

1.either a face

2.one of twelve edges and always land on the side which makes angle less than 45 assuming sufficient friction.

3.On a corner and proceed to go on and land on the edge with angle less than 60

These are the only possible cases that come to mind finally after inelasticity of collisions leads to landing.

A mathematical model based on these cases could be drawn with parameters of initial potential and kinetic energies, momentum and angular momentum to predict which of the cases befall up until each bounce and until the energy is dissipated enough to predict a certain number on dice.

Procuring these four initial arguments with reasonable accuracy will give close to accurate number on dice.

- 137