Consider a $n$-sided regular (convex) polygon and its circumscribed circle of radius $r$, centered in $(0,0)$. Fixing $(r,0)$ as the coordinate of the first vertex, the $n$ vertices of the polygon are given by:

$$P_i = (x_i,y_i)=(r\cos(2i\pi/n),r\sin(2i\pi/n))$$

The second moment of inertia w.r.t. the $x$-axis can then be derived using

$$ {\displaystyle I_{x}={\frac {1}{12}}\sum _{i=1}^{n}(y_{i}^{2}+y_{i}y_{i+1}+y_{i+1}^{2})(x_{i}y_{i+1}-x_{i+1}y_{i})}$$ leading to the result $I_x=nr^4/48\ (4\sin(2\pi/n)+\sin(4\pi/n))$.

Very interestingly, this value does not depend on the axis, or equivalently, on the rotation of the polygon: for example the two following hexagons have the same second moment of area wrt to the $x$-axis:

To show this, I multiplied $(x_i,y_i)$ by a rotation of matrix of angle $\theta$, leading to

$$P_i=(r\cos(2i\pi/n +\theta),r\sin(2i\pi/n + \theta)$$

Then, I computed $I_x(\theta)$ and using symbolic computation, observed that $I_x'(\theta)=0$.

Question Can the fact that $I_x$ does not depend on $\theta$ be seen easily by hand? Are there intuitive reasons for that?

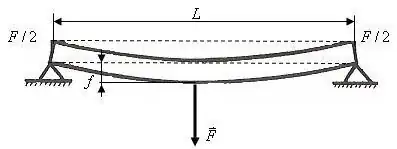

Side note on mechanics This is interesting because it means the deflexion of a beam---the displacement induced by the force $F$, (see below)---with a regular-polygonial section does not depend on how the beam is placed. This is completely false for a rectangular section: the deflexion is much higher if the height of the beam corresponds the short side of the rectangle, as you can observe by holding a sheet of paper (slender rectangular section!) in a horizontal plane (huge deflection) or a vertical plane (no observable displacement).