I am aware of a few analytical calculations showing that the stereographic projection sends circles on the sphere to circles on the equatorial plane. There are related questions here.

What about a geometrical proof? I have found one somewhere that goes as follows.

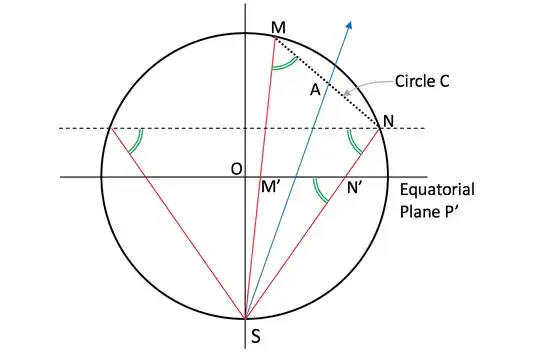

Let $O$ be the center of the sphere and $S$ the pole doing the projection. Choose a circle $C$ on the sphere lying on a plane $P$, and denote its center $A$. The rays joining $S$ to the circle $C$ cross the equatorial plane $P'$ at some points, which we want to prove form another circle. Let $M$ and $N$ be the two points on the circle $C$ such that they belong to the $SOA$ plane. Their stereographic projection on the equatorial plane are denoted by $M'$ and $N'$.

The angles noted in the attached figure can easily be proven equal, leading to the two angles $SMN$ and $SN'M'$ being equal. This means that the planes $P$ and $P'$ are symmetrical to each other by reflection across the axis $SA$ (shown as an arrow). Now, the proof follows saying that the "cone" from $S$ to $C$ has the same symmetry, so that its intersections with the two planes $P$ and $P'$ are "equivalent". As a consequence, the two intersections are circles, and this proves the theorem.

But wait. To me, this is not really a "cone". But fine, it does not need to be. However, it does not seem symmetrical across $SA$: taking the symmetric point of $N$ or $M$ will clearly not land on the same "cone". So that would mean that the two shapes made by intersecting with $P$ and $P'$ should not be equivalent; consequently, stereographic projection would not send circles to circles.

Where is my error?