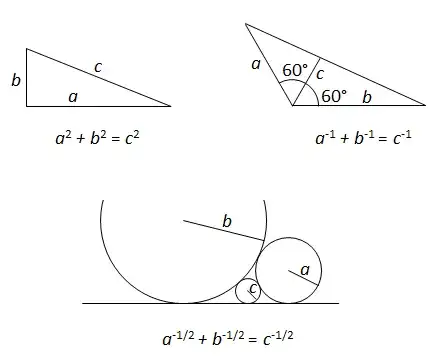

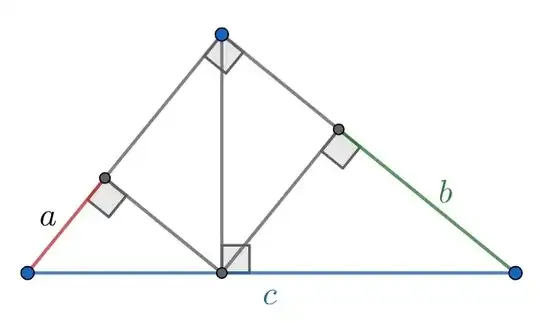

- The Pythagorean theorem.

- Let $A$, $C$, $B$ be three points on a line in this order, and let $D$ be another point, such that $\angle ADC =\angle CDB = 60^\circ$. Let $a=AD$, $b=BD$, $c=CD$. Then, $$a^{-1} + b^{-1} = c^{-1}.$$

- Let $C_1$, $C_2$, $C_3$ be three circles that are tangent to each other and also tangent to a common line, such that $C_3$ lies between $C_1$ and $C_2$. Let $a$, $b$, $c$ be their respective radii. Then, $$a^{-1/2} + b^{-1/2} = c^{-1/2}.$$

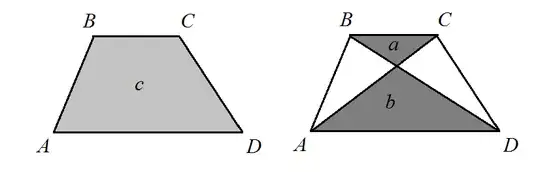

See the figure below.

Are there any other results of this type in geometry?