I will add some extended comments. I do not know how to answer this question:

OP. My question is, is there some reason this is so linear that I'm not seeing? The only thing it seems to indicate to me is that there truly must be infinitely many twin primes.

In the above, I see one question, and two statements. The first statement is that the plot is "so linear". I am not convinced that it is indeed linear, and I comment on this below. (I admit it looked linear to me at first.) If the plot is not linear then formally the question is void, but I do find the plot interesting, and I provide some further support (in the form of more plots) that it is indeed more or less linear, if not in the sense of a "straight line" then at least in the sense of a "thin curve" (with a gradually decreasing slope, where perhaps slope remains positive all the time but who knows). I do not know if there is a reason for that (but on the other hand, there is a reason for everything :). From the plots below it seems that taking primes $p$ only, in $(3pn-4,3pn-2)$

(as opposed to taking odd numbers $m$ in general, in $(3mn-4,3mn-2)$) does seem to contribute to the "thinness" of the curve. Finally, concerning the statement that there truly must be infinitely many twin primes, it doesn't look like use of the word "truly" on its own constitutes a proof ;)

So, first I was confused as to what exactly was plotted, and eventually it was cleared (to me, after guessing incorrectly twice) in the comments. The OP also edited the question to supply a clarification, but I find it confusing to use the same letter $n$ in two inconsistent ways, on one hand $p=p_n$, the $n$-th prime, and, on the other hand, odd $n<p$, in $(3pn-4,3pn-2)$.

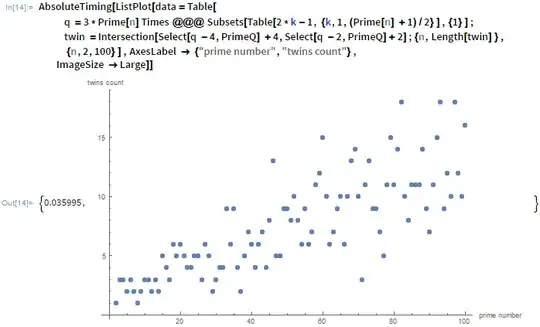

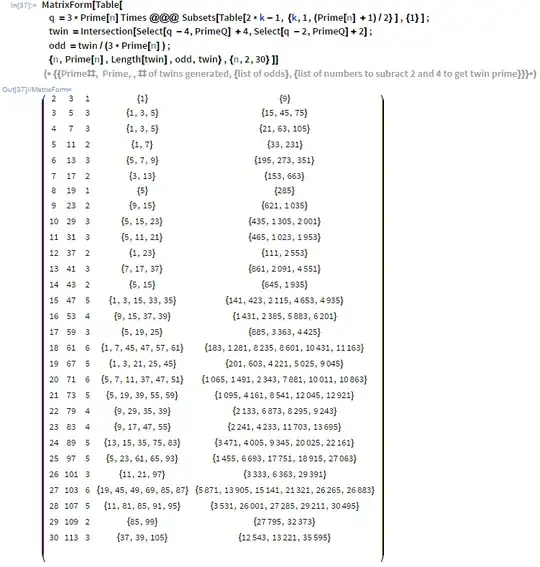

So, below $p_k$ will denote the $k$-th prime, like $p_1=2$, $p_2=3$, $p_3=5$, etc. What the OP does for primes $p$ could as well be done for odd

integers $m\ge3$ in general. Given $m$ let $g(m)$ denote the quantity of good, odd $n<m$ for which $(3mn-4,3mn-2)$ is a twin-prime pair. For example, when $m=5$ then we could take $n=1,3$. Then $n=1$ is good since it results in the twin-prime pair $(3mn-4,3mn-2)=(11,13)$. Also, $n=3$ is good since it results in the twin-prime pair $(3mn-4,3mn-2)=(41,43)$. This $g(5)=2$ since there are two good values for $n$, namely $n=1$ and $n=3$, that work. On the other hand if $m=9$ then possible values for $n$ are $n=1,3,5,7$ and none of them is good. Indeed $n=1$ gives $(3mn-4,3mn-2)=(23,25)$, not good (as $25$ is not a prime), $n=3$ gives $(77,79)$ not good, $n=5$ gives $(131,133=7\cdot19)$ not good, and $n=7$ gives $(185,187)$ not good. Thus $g(9)=0$ (and it seems that $m=9$ is the only odd $m\ge3$ with $g(m)=0$, at least this is so, for $3\le m\le 55227$, as far as I computed).

One may contemplate variations of $g(m)$, for example $\bar g(m)$ would count the number of good odd $n\le m$ (instead of $n<m$), and

$\tilde g(m)$ would count the number of good odd $n\le m^2$. Then for example $\bar g(9)=1$ since $n=9$ is good, resulting in twin-prime pair $(239,241)$. Also, $\tilde g(9)=9$. For now I will stick with $g(m)$, following OP, but it might be worth looking at versions of $g(m)$ obtained by replacing odd $n<m$ with odd $n\le b(m)$ for a suitable fixed bound function $b(m)$.

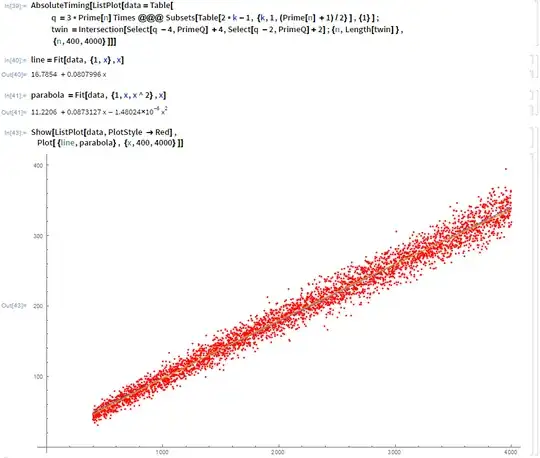

Using $g(m)$ we could define $f(k)=g(p_k)$, where $p_k$ is the $k$-th prime number. For example, $f(2)=g(3)=1$, $f(3)=g(5)=2$, $f(4)=g(7)=3$, and $f(400)=g(p_{400})=g(2741)=39$. My understanding is that the plot posted by the OP represents $f(k)$ vs $k$ for $k$ from $400$ to $4000$ (although this notation was not used). For example the point $(400,39)$ belongs to the plot.

As I noted in a comment, I am not convinced that I am seeing a straight line. If a larger range of values of $k$ is considered, then it seems that the plot is concave down, with the slope gradually decreasing. For smaller primes, around $p_{150}$, i.e. when $k=150$, the slope may be around $0.10$, for larger primes like posted by OP $400<k<4000$ the slope may be around $0.08$, for yet larger primes like $p_{150010}=2015309$, i.e. $k=150010$ the slope seems closer to $0.063$. (This is based on my computations and estimates using Computer Algebra Reduce, a link to this software is posted in the comments, it has a predicate primep$(p)$ returning true if $p$ is a prime. Using Reduce I made tables of values which were then used to make plots, using Graph of Ivan Johansen.)

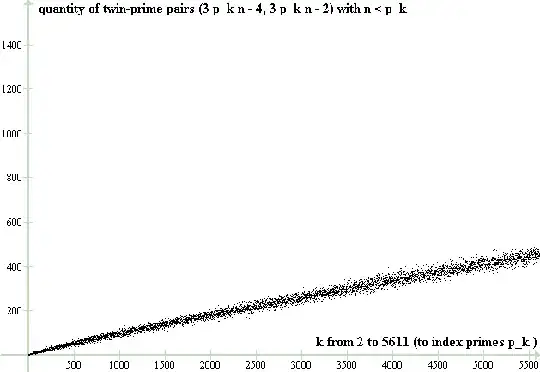

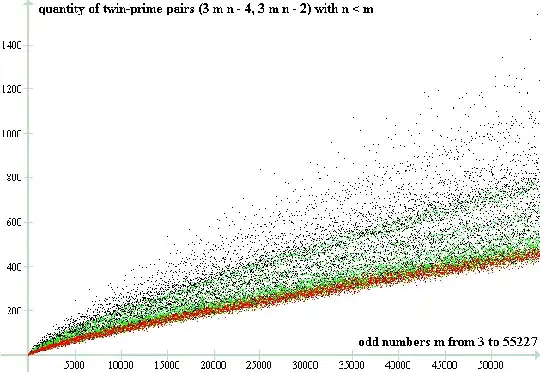

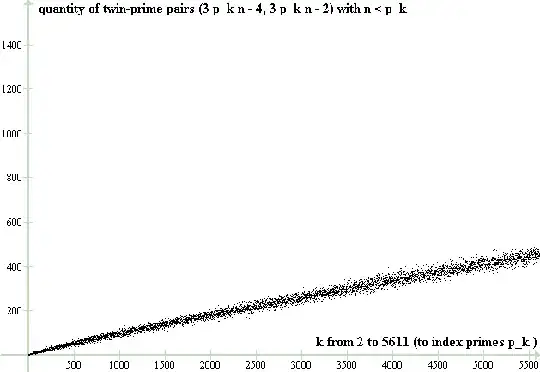

Here is a plot of $f(k)$ vs $k$ for $2\le k\le5611$. Note that $p_{5611}=55219$.

This plot does resemble a straight line. But an estimate of its slope (using the right half of the plot) gives about $0.074$, whereas the OP has an estimate for the slope about $0.08$ or $0.081$ based on $400\le k \le 4000$. As noted earlier my estimate for the slope when $k=150010$ is less than $0.063$. If the slope is gradually decreasing then this is not a straight line. (Of course even if the "slope" appears to approach $0$ but remain positive all the time, then this will prove the infinitude of twin-prime pairs, but this would need more precise language and proofs.)

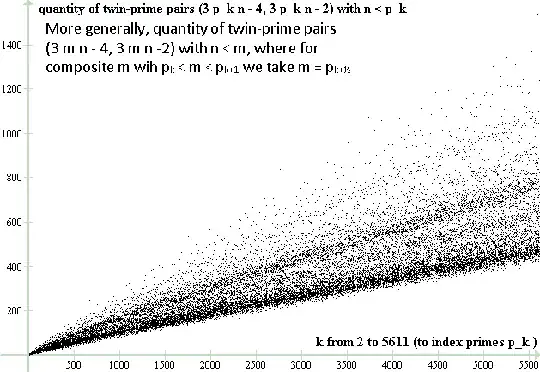

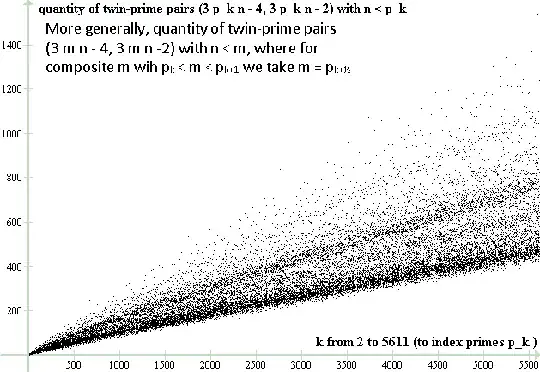

As I see no particular reason to only consider $n<p_k$ (as opposed to $n\le b(p_k)$ for a suitable fixed function $b$), I also do not see a formal reason to restrict these considerations to primes $p_k$ only. That is,

$g(m)$ is defined for all odd $m\ge3$, not only for $m=p_k$, and we may try to plot it. A technical question arises: If we keep $k$ on the horizontal axis, then, given $m$, what $k$ does it correspond to? In the plot below I have chosen to plot the point $(k+\frac12,g(m))$ whenever $m\ge3$ is a composite odd number with $p_k<m<p_{k+1}$. Given the scales involved this choice seems just fine, and the plot below is an extension of the plot given earlier.

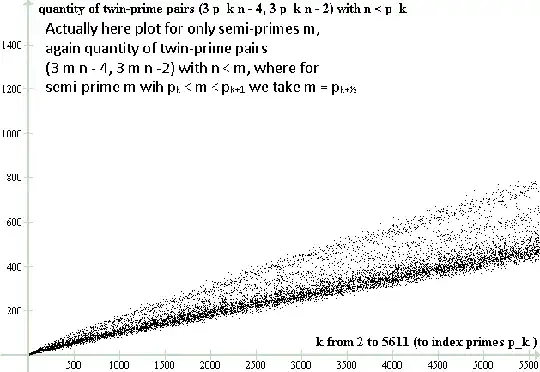

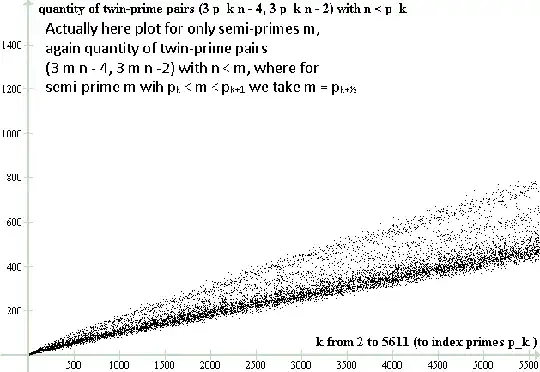

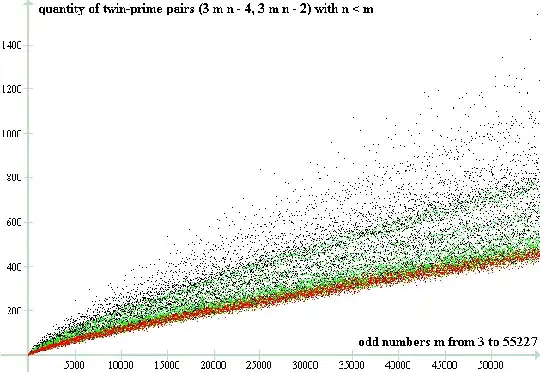

Obviously the new plot (involving composite odd numbers as well as primes) is much more spread out, along the vertical, than the old plot (only involving primes). The primes seem to generate just one belt at the lower part of the plot, and there seem to be some structure, involving belts further up. I thought perhaps semi-primes have their own belt, but this does not seem to be the case. Although the plot for the semi-primes only, given below, is not spread out along the vertical direction nearly as much as the plot for all composite numbers, the plot for semi-primes seems nevertheless itself to include two or three belts (one of them coinciding with the belt coming from the primes). Lo and behold, is there a reason for all this, I guess someone working in number-theory may have a good laugh if the reason for them is obvious, but I didn't even try to figure it out, just making an observation (and contributing to the puzzle offered by the OP).

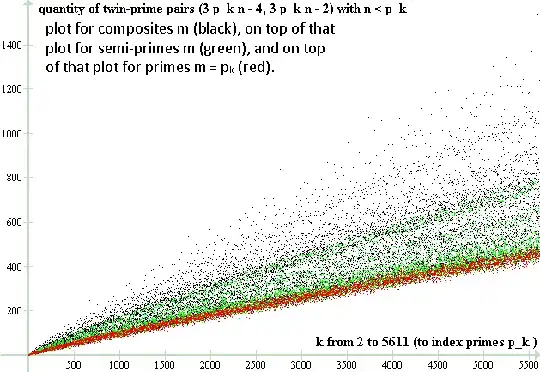

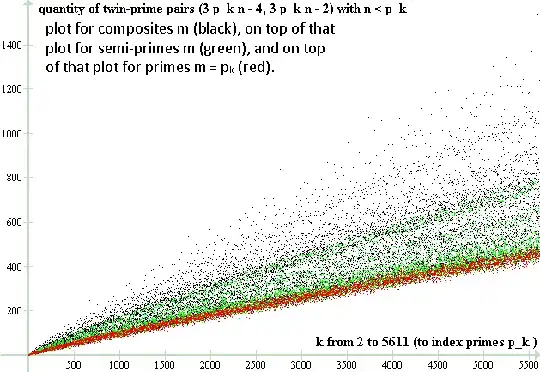

Here are all three plots, for primes, composites, and semi-primes together.

(Composites in black, semi-primes painted over in green, and primes painted over in red.)

As already indicated, the above are plots of $f(k)=g(p_k)$ vs $k$. I had an incorrect interpretation earlier as to what was plotted by OP, I thought it was a plot of $g(m)$ vs $m$ (and I had included a link to a plot of $g(m)$ vs $m$ in the comments, just because it was quicker to make the plot that way).

But the plot of $f(k)=g(p_k)$ vs $k$ looks better than the plot of

$g(m)$ vs $m$ since the latter plot looks concave down in a more pronounced way, whereas the former looks more like a straight line, even if it is concave down too, when one looks more carefully. For comparison, here is the plot of $g(m)$ vs $m$ for $3\le m\le 55227$, which includes virtually the same range of primes as before, but, if $m=p_k$, then this time $m$ is on the horizontal axis instead of $k$.

The OP had observed that: If each prime were a bucket filled with at least one unique twin prime, infinite primes (proven) would imply infinite twin primes (conjectured only). As discussed in the comments this uniqueness is lost when one considers $g(m)$ in general for odd $m\ge 3$ instead of only $f(k)=g(p_k)$ for primes $p_k$. More precisely, if $k<j$ and $n<p_k$ with $(3 p_k n - 4,3 p_k n - 2)$ a twin-prime pair, and if $l<p_j$

with $(3 p_j l - 4,3 p_j l - 2)$ a twin-prime pair, then necessarily

$3 p_k n - 4\not=3 p_j l - 4$ since $p_k n\not=p_j l$ for the largest prime factor of $p_k n$ is $p_k$ while the largest prime factor of

$p_j l$ is $p_j>p_k$. This uniqueness argument fails if $p_k$ is replaced by a general odd number $m$, but I am not concerned about this. Indeed $3 m n -4\ge 3 m -4$, and the numbers $3 m -4$ go to infinity as $m$ goes to infinity, so if there are infinitely many odd $m$ for each of which there is at least one good odd $n<m$, then this would imply the existence of infinitely many twin-prime pairs. Thus one possible modification of what the OP proposes is to simultaneously: (1) come up with a nice bounding function $b(m)$ so we consider all odd $n\le b(m)$ instead of odd $n<m$, and (2) come up with a suitable sub-sequence of the odd numbers, say a sequence $\{m_i:i=1,2,3\dots\}$ such that $g(m_i)$ is easy to evaluate, or at the very least such that one could show that $g(m_i)\ge1$ for each $i$. Restated in this way, I do not see how this problem would perhaps be any easier than the twin-prime conjecture itself, I see no suitable candidates for either $b(m)$ of for a sub-sequence of the odd primes (that is, I didn't really think about it, but I don't seem to have ideas how to start). With this notation, the OP seems to suggest that $b(m)=m-1$ is a natural answer for (1), and that the sequence of odd primes is a natural answer to (2). Perhaps these plots provide some evidence, but on one hand, these plots did not involve very large primes, and on the other hand even if one could precisely state what is seen on these plots and believe it, and even if it is true, one wouldn't know that it is true without a proof. What exactly do these plots show, if anything?

For more on why these plots look the way they do, one may google and listen to the song "Turn,Turn,Turn" by The Byrds (but I won't provide a link, as the answer there does not employ a mathematical argument. You might want to replace season with reason, as you listen ;)

Edit. It may be curious to look at some of the high points on these plots, corresponding to large yield $g(m)$ for some composite $m$ (compared to $g(m')$ for neighboring $m'$). Some of these are $g(15015)=536=g(p_{1755\frac12})$ (though notation $p_{k\frac12}$ is in general ambiguous since it may denote any of several composite numbers between $p_k$ and $p_{k+1}$),

$g(19635)=656=g(p_{2225\frac12})$,

$g(25025)=837=g(p_{2763\frac12})$,

$g(35035)=1072=g(p_{3734\frac12})$,

$g(45045)=1288=g(p_{4677\frac12})$, and

$g(55055)=1537=g(p_{5595\frac12})$. All of these $m$ listed above except $19635$ are multiples of $1001=7\cdot11\cdot13$. More precisely, $15015=3\cdot5\cdot7\cdot11\cdot13$,

$19635=3\cdot5\cdot7\cdot11\cdot17$,

$25025=5^2\cdot7\cdot11\cdot13$,

$35035=5\cdot7^2\cdot11\cdot13$,

$45045=3^2\cdot5\cdot7\cdot11\cdot13$,

$55055=5\cdot7\cdot11^2\cdot13$. Clearly twin-primes has something to do with Scheherazade. One may conjecture that when $m$ is highly composite (e.g. product of many, preferably different, small primes) then $g(m)$ is large. This is what the plots might suggest. (So called smooth numbers seem related, they have been studied for their applications in factoring algorithms, Wikipedia has a page on that.) One may look for a suitable sequence of odd integers, perhaps a sequence of suitably chosen(?) smooth numbers, say $\{m_i:i=1,2,3,\dots\}$ such that the plot of $g$, when restricted to these $m_i$ only, looks like a line, except that this "line" will have a "bigger slope" as compared to the "line" that goes with $g(p_k)$ for primes $p_k$.

Table[ q =3* Prime[n] Times@@@Subsets[Table[2*k-1, {k, 1,(Prime[n] + 1)/2}],{1}]; odd =twin/(3*Prime[n]); twin = Intersection[Select[q - 4, PrimeQ] + 4, Select[q - 2, PrimeQ]+2];{n,Prime[n],twin,Length[twin],odd}, {n, 401, 401}] (* {{Prime#, Prime, {list of numbers to subract 2 and 4 to get twin prime}, # of odds, {list of odds}"}}*)– Elem-Teach-w-Bach-n-Math-Ed Mar 30 '16 at 03:11