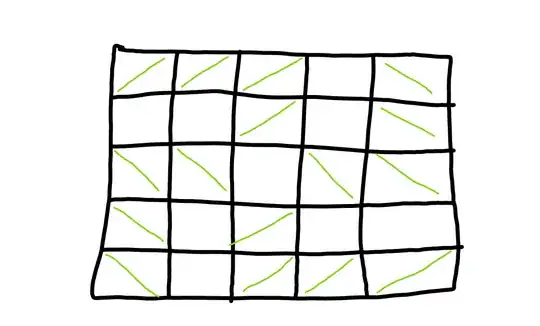

Draw a 5x5 square. In 16 of 25 squares draw diagonals in such a way that no diagonal ends touch. How can I do this?

-

What makes you believe that a solution exists? – John Hughes Oct 26 '15 at 17:55

-

1I assume you mean "draw diagonals in 16 of the 25 small squares." I also suspect that no such drawing is possible. – John Hughes Oct 26 '15 at 18:03

-

Two small-square diagonals touch if they share an endpoint. – John Hughes Oct 26 '15 at 18:12

-

No, two in the same square are not allowed. – McLinux Oct 26 '15 at 18:41

-

6Isn't this a duplicate of this question? Observe that there is a link to a solution – Jyrki Lahtonen Oct 26 '15 at 18:59

-

3"If it is fun, it is most likely a duplicate" (MSE conjecture) – mvw Oct 26 '15 at 19:24

-

I don't think this question should be closed if the OP extends it to ask for a proof that 16 is optimal - that hasn't been answered yet. – Rob Arthan Oct 26 '15 at 21:16

-

@RobArthan This should be answerable by a computer search. Is that acceptable here? – Captain Giraffe Oct 27 '15 at 00:10

-

@CaptainGiraffe: I don't set the rules for MSE. But the answers and comments already answer the question. – Rob Arthan Oct 27 '15 at 00:13

-

@RobArthan I was thinking finding the optimum. – Captain Giraffe Oct 27 '15 at 00:54

4 Answers

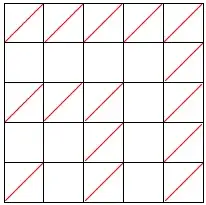

Posting a CW-copy of the image (linked to) given as a solution to the duplicate question. Just in case the link rots :-/

- 140,891

-

Counting the vertices (as in John's answer) makes it immediately clear that more than 17 is impossible. Out of the 36 available vertices at least one on the top border and one on the bottom border must remain unused, because only five diagonals can use a vertex on those borders. The same applies, of course, to left/ right borders, but that leaves open the possibility that two diagonally opposite corners remain unused. An argument telling that 17 is impossible is surely out there. Anyone? – Jyrki Lahtonen Oct 26 '15 at 19:23

-

-

1Give yourself a break, @John. Your attempt started out fine. Surely counting the used vertices (two per drawn diagonal) is the key to proving any upper bounds here – Jyrki Lahtonen Oct 26 '15 at 19:36

-

1Following @JyrkiLahtonen's argument: For a solution with 17, we need to us at least two of the diagonal vertices. As each side needs an unused vertex, two opposing vertices are unused and all other $34$ vertices are used. However, this leads to all outer squares being used and all with diagonally of the same direction (start filling from the used outer vertices), which is not possible – Hagen von Eitzen Oct 26 '15 at 22:01

-

Here's an argument why $16$ is optimal. Let $r_i$ be the number of diagonals drawn in the $i$-th row of squares. (So in the claimed optimal solution $r_1 = r_3 = r_5 = 4$ and $r_2 = r_4 = 2$.) Then $0 \le r_i \le 5$, and because each diagonal in row $i$ eliminates $1$ of the $6$ upper vertices for a a diagonal in row $i + 1$, we have $r_{i+1} \le 6 - r_i$. Let $d_{i+1} = 6 - r_i - r_{i+1}$ be the error in this inequality so that $d_{i+1} \ge 0$ and $r_{i+1} = 6 - r_i - d_{i+1}$. (So the $d_i$ are all $0$ in the claimed optimal solution.) The total number of diagonals is then:

$$ r_1 + r_2 + r_3 + r_4 + r_5= r_1 + 12 - d_3 - d_5 \le 17 $$

and we can only have equality if $r_1 = 5$ and $d_3 = d_5 = 0$. However, if $r_1 = 5$ and $r_2 = 1$, $r_3$ cannot be $5$ because the diagonal in row $2$ cannot have its lower vertex on the boundary of the array of squares. So $d_3 > 0$ and the optimal solution does indeed have at most $16$ diagonals as claimed.

- 51,538

- 4

- 53

- 105

- 266

-

2I agree, you could also achieve the same by drawing / in all "odd" lines. – implicati0n Oct 26 '15 at 18:16

Here's a wrong (alas) proof that it can't be done.

There are 36 vertices in the grid.

Suppose you had a solution.

Your 16 diagonals will use up 32 of these vertices. So exactly four vertices are unused.

There are also 50 possible diagonals. Each (internal) vertex that goes unused corresponds to at most four edges that cannot be used. [N.B., added after comments: at this point the remainder of the argument is flawed, for there are other ways for an edge to be unused -- like other edges using one of its two endpoints. D'oh!] An external vertex corresponds to either 2 or 1 unused diagonals. So the largest number of unused diagonals in any arrangement that leaves only four unused vertices is 16. That means such an arrangement uses at least 34 diagonals. That's a contradiction.

- 100,827

- 4

- 86

- 159

-

1I don't get the last paragraph at all. If I followed correctly we can replace the numbers in "$16$ diagonals", "$32$ vertices", "$4$ vertices" "$16$ unused vertices" and "at least $36$ diagonals" with $15,30,6,24,26$ respectively which shows you can't draw $15$ diagonals. Which is obviously possible. (where does that last $36$ come from anyway ?) – mercio Oct 26 '15 at 18:51

-

2A solution has been posted, which means that you've made a mistake somewhere. – Akiva Weinberger Oct 26 '15 at 19:17

-

2Why downvote this? The idea to think about the vertices is a nice one. Even if there is an error in the argumentation. – mvw Oct 26 '15 at 19:21

-

1Oops. 36 came from 50 - 16, which shows that I shouldn't be allowed to do arithmetic until my 20th cup of tea. :( And as Akiva points out, there's evidently an error in my proof (even above and beyond this small one.) – John Hughes Oct 26 '15 at 19:31