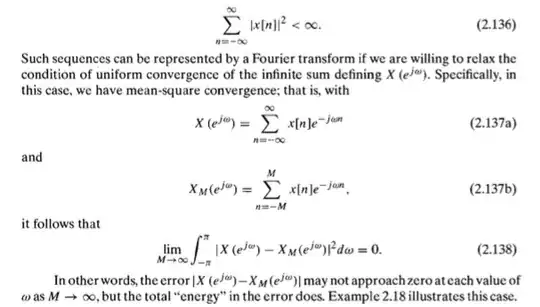

I'm having trouble what exactly is converging here. From what I understand, $X$ doesn't necessarily exist. If it doesn't exist, how can we say that $X_m$ converges to it in the mean square sense? How can you converge to something that doesn't exist?

Asked

Active

Viewed 416 times

1

-

A result that may be helpful: if a sequence converges in $L^2$, then a subsequence converges almost everywhere, to the same limit. Yet a sequence can converge in $L^2$ without converging pointwise anywhere; the classic example is the "moving block". Cf. http://math.stackexchange.com/questions/1415891/almost-everywhere-convergence-versus-convergence-in-measure – Ian Sep 28 '15 at 02:17

-

@Ian But what is it converging to? How can you converge in $L^2$ or point wise to something that doesn't exist? It's like saying "you look a lot like my friend who doesn't exist". – pdfgdfg Sep 28 '15 at 02:28

-

The simplest way would be to have $X$ actually converging for almost every $\omega$; then the sum properly defines a function in the sense of $L^2$ and everything is OK. I'm not sure that occurs in your situation. – Ian Sep 28 '15 at 02:45

1 Answers

2

The proper way to state this is that the sequence $(X_M)_M$ defined in (2.137b) is Cauchy in $L^2$ under the assumption (2.136).

Thus, this sequence has some limit (in the $L^2$ sense) $X \in L^2$ by completeness.

Because if the special form of the $X_M$ (partial sums), a common way to denote the limit $X$ is as in (2.137a).

Finally, some subsequence of $(X_M)_M$ will also converge pointwise a.e. to $X$.

PhoemueX

- 36,211