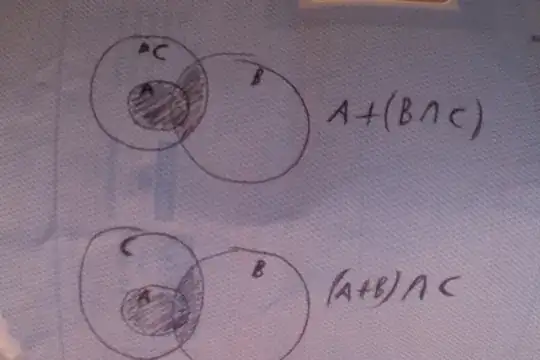

I'm not sure if the statement is obvious to you but in general $+$ and $\cap$ don't distribute over each other. I wouldn't expect them to either since $\cap$ is a set theoretic operation and $+$ is only defined for modules/ideals/abelian groups. However, when $A\subset C$ they do distribute over one another.

But the proof shouldn't go something like this:

$$A+(B\cap C)=(A+B)\cap (A+C)=(A+B)\cap C $$ where the last equality comes from $A\subset C$ because here we assumed they distribute in the first place which is false in general. So any proof of this fact can't use the above method (or the other direction).

An explicit example that these operations don't distribute is by taking the submodules of the $\mathbb{Z}[X]$-module $\mathbb{Z}[X]$ where we can now just look at ideals

$A=(2)$, $B=(x-1)$, and $C=(x+1)$

then $$A+(B\cap C)=(2)+(x^2-1)=(2,x^2-1)$$

and $$A+ B \cap A+ C=(2,x-1)\cap(2,x+1)=(2,x+1)$$

since $(2,x-1)=(2,x+1)$.