Forecasting the Future with a Positive Stochastic Matrix

My favorite application is: forecast the future!

I will give an example I use in presentations to undergrads. Some words in the images are in portuguese but you do not need to understand that.

Imagine three buckets that initially contain a total of $1$ Kg of sand:

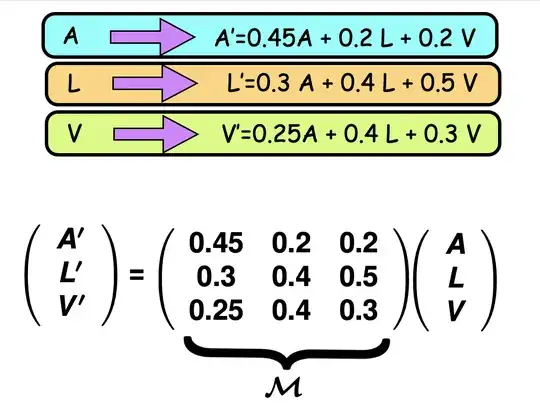

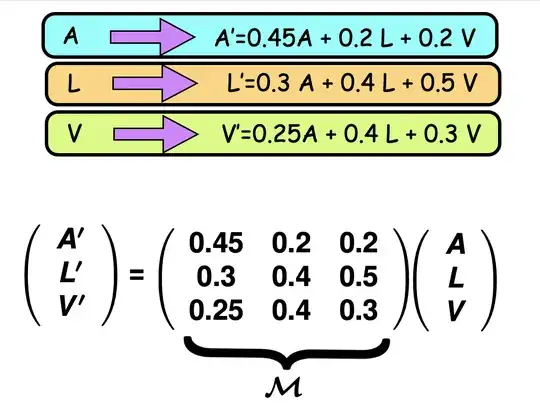

At every step, sand is redistributed according to fixed percentages in the image below. I move 20% of the sand of the bucket $V$ to the bucket $A$, 50% of the sand in the bucket $V$ to the bucket $L$,...

Let the starting distribution be $(A,L,V)$ and the distribution after one step be $(A',L',V')$.

Because the rule is linear we have

$$

(A',L',V') \;=\; M\,(A,L,V),

$$

where $M$ is a matrix that has two notable properties:

(1) All entries are positive. One application of the process mixes the sand thoroughly—some sand from every bucket ends up in every other bucket.

(2) Each column sums to 1. No sand is lost or added during the transfer.

Such a matrix is called a positive stochastic matrix.

Now repeat the same procedure indefinitely. The natural question is:

What happens to the sand distribution after many iterations?

This is kind of complicate, since to calculate the distribution of the sand after $n$ iterations you would need to calculate $M^n$ and multiply by the original distribution $(A,L,V)$

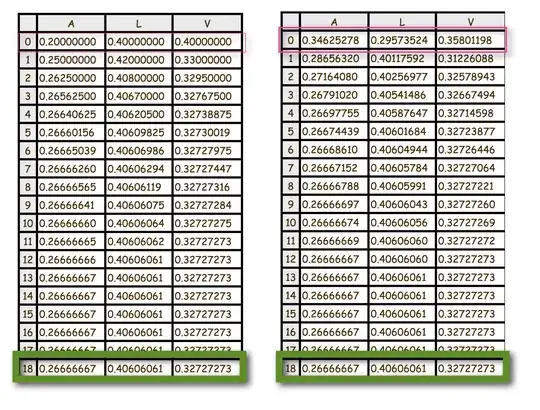

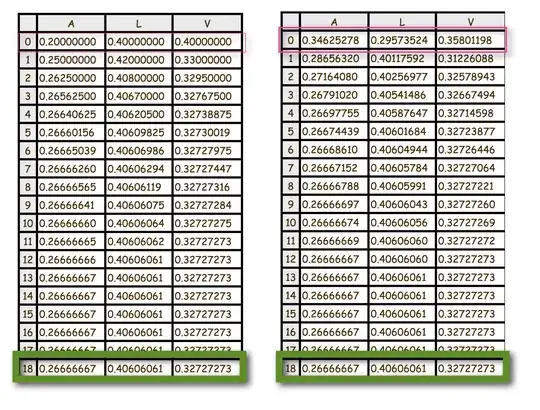

which is tedious by hand. Since computer can do this very fast, we can do an experiment using a spreadsheet software. It is quite easy. You see below two of my experiments

in the first experiment I put

0.200 Kg in bucket A

0.400 Kg in bucket L

0.400 Kg in bucket V

and I repeat the process 18 times. In the end I got the distribution

(0.2666667, 0.40606061, 0.32727273)

Surprisingly, the distribution of sand stabilises after only four iterations—already matching to three decimal places!

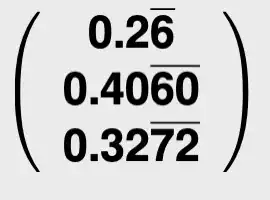

Even more remarkable is that, if I begin with a completely different initial distribution, the sand still settles into the same stable pattern. In the second experiment I chose random amounts for the first two buckets, then added enough sand to the third so the total mass was exactly 1 kg. Once again, the distribution converged to the same limit. Try as many distinct

1 kg distributions as you like—the outcome is always identical!

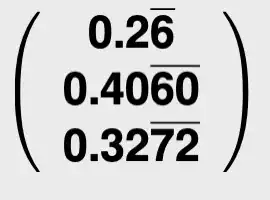

What is this special distribution (0.2666667, 0.40606061, 0.32727273)? Well this is (approximately ) the distribution

and this vector is an eigenvector for the eigenvalue $1$! Indeed $1$ is the eigenvalue with the largest modulus of the matrix $M$ and its eigen-space is generated by this positive vector. This vetor is the only $1$-eigenvector whose sum of coordinates is $1$.

Like I said, this lets you forecast the future sand distribution in this linear system: even if you don’t know the starting layout (only the total amount of sand), after a few rounds the mix will be very, very close to that

1-eigenvector. Just run the experiment once and you’ve got the answer!

The Perron--Frobenius Theorem says this trick scales to any number of buckets. Got $10^{23}$ of them? As long as your mixing matrix is positive (every entry $>0$) and you’re not losing or adding sand, it doesn’t matter how you first spread the 1kg. Keep repeating the mix and, as $n \to \infty$, the sand always settles into one special vector---the unique eigenvector for eigenvalue $1$ whose coordinates add up to $1$. You can even estimate the rate of convergence (that is always exponential).

MAGIC!

There’s a similar idea for continuous mass distributions driven by chaotic dynamical systems. In that setting, the mass evolution is modeled by a positive linear operator acting on a space of functions (or distributions). This operator—known as the transfer operator (or Ruelle–Perron–Frobenius operator)—is a cornerstone of Ergodic Theory for analyzing the dynamics of (piecewise) smooth maps.