Suppose $\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \alpha_3 $ are complex numbers which are not collinear. Is it possible to use some geometry to find the center of the circle that contains $\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \alpha_3 $ ?

6 Answers

To find the point of intersection of the perpendicular bisectors, we need to find real $s$ and $t$ so that $$ \overbrace{\frac{\alpha_1+\alpha_2}2+is\frac{\alpha_1-\alpha_2}2}^{\text{perpendicular bisector of }\overrightarrow{\alpha_1\alpha_2}}=\overbrace{\frac{\alpha_2+\alpha_3}2+it\frac{\alpha_2-\alpha_3}2}^{\text{perpendicular bisector of }\overrightarrow{\alpha_2\alpha_3}}\tag{1} $$

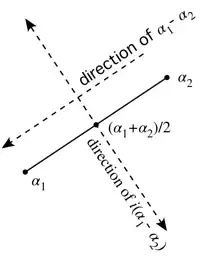

Here is a diagram of the geometry behind $(1)$

$(1)$ is equivalent to $$ s(\alpha_1-\alpha_2)+t(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)=i(\alpha_1-\alpha_3)\tag{2} $$ Multiply $(2)$ by $\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}$ to get $$ s(\alpha_1-\alpha_2)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}+t|\alpha_3-\alpha_2|^2=i(\alpha_1-\alpha_3)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}\tag{3} $$ Consider imaginary parts of $(3)$ to get $$ \begin{align} s &=\frac{\mathrm{Im}\left(i(\alpha_1-\alpha_3)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}\right)}{\mathrm{Im}\left((\alpha_1-\alpha_2)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}\right)}\\ &=\frac{\mathrm{Re}\left((\alpha_3-\alpha_1)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}\right)}{\mathrm{Im}\left((\alpha_3-\alpha_1)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}\right)}\tag{4} \end{align} $$ Multiply $(2)$ by $\overline{(\alpha_1-\alpha_2)}$ to get $$ s|\alpha_1-\alpha_2|^2+t(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)\overline{(\alpha_1-\alpha_2)}=i(\alpha_1-\alpha_3)\overline{(\alpha_1-\alpha_2)}\tag{5} $$ Consider imaginary parts of $(5)$ to get $$ \begin{align} t &=\frac{\mathrm{Im}\left(i(\alpha_1-\alpha_3)\overline{(\alpha_1-\alpha_2)}\right)}{\mathrm{Im}\left((\alpha_3-\alpha_2)\overline{(\alpha_1-\alpha_2)}\right)}\\ &=\frac{\mathrm{Re}\left((\alpha_2-\alpha_1)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_1)}\right)}{\mathrm{Im}\left((\alpha_2-\alpha_1)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_1)}\right)}\tag{6} \end{align} $$ Plug either $(4)$ or $(6)$ into $(1)$ to get the center of the circle.

Example

If $$ \alpha_1=3+4i,\quad\alpha_2=1-i,\quad\alpha_3=2+i $$ then $$ s=\frac{\mathrm{Re}((-1-3i)(1-2i))}{\mathrm{Im}((-1-3i)(1-2i))}=\frac{\mathrm{Re}(-7-i)}{\mathrm{Im}(-7-i)}=7 $$ and $$ t=\frac{\mathrm{Re}((-2-5i)(-1+3i))}{\mathrm{Im}((-2-5i)(-1+3i))}=\frac{\mathrm{Re}(17-i)}{\mathrm{Im}(17-i)}=-17 $$ Plug $s$ and $t$ into $(1)$: $$ \frac{4+3i}2+7i\frac{2+5i}2=\frac{-31+17i}2=\frac{3}2-17i\frac{-1-2i}2 $$ So the center is $$ c=\frac{-31+17i}2 $$ As a check, we can compute the square of the distance to each point: $$ |\alpha_1-c|^2=\left|\frac{37-9i}2\right|^2=\frac{725}2\\ |\alpha_2-c|^2=\left|\frac{33-19i}2\right|^2=\frac{725}2\\ |\alpha_3-c|^2=\left|\frac{35-15i}2\right|^2=\frac{725}2 $$

- 353,833

-

So, the center of the circle would be $s + it $ ? – Feb 12 '15 at 13:36

-

No, the center of the circle is the point common to the two perpendicular bisectors. Plug $s$ from $(6)$ into the left-hand side of $(1)$ or $t$ from $(4)$ into the right-hand side of $(1)$ to get the center of the circle. – robjohn Feb 12 '15 at 13:40

-

I have a question: How do you find the perpendicular bisector of two complex numbers on the circle ? – Feb 13 '15 at 20:18

-

The perpendicular bisector contains the midpoint of the points, say $\frac{\alpha_1+\alpha_2}2$. The perpendicular bisector is perpendicular to the line connecting the points, so it consists of all points which are in the direction $i(\alpha_1-\alpha_2)$ from the midpoint. Thus, we get $$\frac{\alpha_1+\alpha_2}2+is\frac{\alpha_1-\alpha_2}2$$ – robjohn Feb 13 '15 at 22:33

-

Got it. I don't understand why $$ Im( ( \alpha_1 - \alpha_2) \overline{ ( \alpha_3 - \alpha_2 ) }) = Im( ( \alpha_3 - \alpha_1) \overline{ ( \alpha_3 - \alpha_2 )}) $$ – Feb 13 '15 at 23:43

-

in equation (4) – Feb 13 '15 at 23:43

-

They are not equal; they are negatives of each other (note that the numerator is negated as well). The difference between $(\alpha_3-\alpha_1)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}$ and $(\alpha_2-\alpha_1)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}$ is $(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)\overline{(\alpha_3-\alpha_2)}=|\alpha_3-\alpha_2|^2$ which is real. Thus, their imaginary parts are equal. – robjohn Feb 13 '15 at 23:50

-

I understand. So, pretty much I don't need to find $t$ in my proof. Just $s$ will be enough. correct ? – Feb 14 '15 at 00:16

-

@Szebo: That's correct. I computed both so that I could double-check the result. – robjohn Feb 14 '15 at 00:37

Using some geometry, we'd simply take the intersection of the perpendicular bisectors.

- 382,479

Here is a solution with a somewhat different flavor. Using DFT we can write the three points $a_j$ in the form $$a_j=m+p\omega^j+q\omega^{-j}\ ,$$ where $\omega:=e^{2\pi i/3}$, and $$m:={1\over3}(a_1+a_2+a_3),\quad p:={1\over3}(a_1\bar\omega +a_2\omega+a_3),\quad q:={1\over3}(a_1\omega +a_2\bar\omega+a_3)\ .\tag{1}$$ Now we have to choose the point $z$ in such a way that the quantity $$|a_j-z|^2=(m+p\omega^j+q\omega^{-j}-z)(\bar m+\bar p\omega^{-j}+\bar q\omega^j-\bar z)\tag{2}$$ does not depend on $j$. This is the case iff the coefficients $c$ and $\bar c$ of $\omega^j$ and $\omega^{-j}$ resulting after computing the right hand side of $(2)$ are $=0$. Collecting the relevant terms we get $$c=m\bar q+p\bar m-p\bar z+q\bar p-z\bar q\ .$$ This leads to the linear system $$\eqalign{\bar q z+p\bar z&=\bar pq+p\bar m+\bar q m \cr \bar p z+q\bar z&=p\bar q+\bar p m+ q \bar m \ . \cr}$$ Solving for $z$ and plugging in the values $(1)$ gives $$z={(a_2-a_3)|a_1|^2+(a_3-a_1)|a_2|^2+(a_1-a_2)|a_3|^2 \over (a_2-a_3)\bar a_1+(a_3-a_1)\bar a_2+(a_1-a_2)\bar a_3}\ .$$

- 232,144

This is best done in Cartesian coordinates.

Without loss of generality, assume that one of the points is the origin (translate as necessary). Let $(x,y)$ be the coordinates of the center and $r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}$ the radius. Express the squared distance from the center to the two points:

$$(x-x_a)^2+(y-y_a)^2=x^2+y^2\\(x-x_b)^2+(y-y_b)^2=x^2+y^2,$$ or, after simplification $$x_ax+y_ay=\frac{x_a^2+y_a^2}2\\ x_bx+y_by=\frac{x_b^2+y_b^2}2.$$

You know the rest.

-

"The rest" is, I presume, to solve the corresponding linear system, yet this is not a geometric method and translating one of the points to the origin can be pretty forbidden when the three points are given. – Timbuc Feb 10 '15 at 11:45

-

-

@Yver Yeah, well: one point for your sense of humour, but don't matter this: the point is that translating can be forbidden for them. – Timbuc Feb 10 '15 at 13:13

-

I said WLOG, so there is no restriction on the three points. Find out how the generality is restored. – Feb 10 '15 at 13:19

-

That you wrote WLOG not necessarily makes it so, in particular for a beginner, and to restore generality to the proof can be a little messy, but if the student manages I think is fine. +1 – Timbuc Feb 10 '15 at 13:22

-

Set $2u=\alpha_2-\alpha_1$ and $2v=\alpha_3-\alpha_1$.

Express that the bisectors of the points of affix $2u$ and $2v$ have a common point:

$$c=u+riu=v+siv,$$ with $r,s$ real.

Multiply by $v^*$ and take the real part to get rid of $s$.

$$\Re(uv^*)+r\Re(iuv^*)=\Re(uv^*)-r\Im(uv^*)=vv^*.$$ Then, $$r=\frac{\Re(uv^*)-vv^*}{\Im(uv^*)}$$ and $$c=u+\frac{\Re(uv^*)-vv^*}{\Im(uv^*)}iu=u\frac{\Im(uv^*)+i\Re(uv^*)-ivv^*}{\Im(uv^*)}=u\frac{i(uv^*)^*-ivv^*}{\Im(uv^*)}=iuv\frac{u^*-v^*}{\Im(uv^*)}.$$

The seeked center is $\alpha_1+i\dfrac{(\alpha_2-\alpha_1)(\alpha_3-\alpha_1)(\alpha_2-\alpha_3)^*}{2\,\Im((\alpha_2-\alpha_1)(\alpha_3-\alpha_1)^*)}$.

The center $c$ of the circle passing through $z_1$, $z_2$, $z_3$ can be calculated as a quotient of two determinants

$$c(z_1, z_2, z_3) \colon =\frac{ \left | \begin{matrix} 1 & z_1 & |z_1|^2 \\ 1 & z_2 & |z_2|^2 \\ 1 & z_3 & |z_3|^2 \end{matrix} \right | } { \left | \begin{matrix} 1 & z_1 & \bar z_1 \\ 1 & z_2 & \bar z_2 \\ 1 & z_3 & \bar z_3 \end{matrix} \right | }$$

You can see this in the following way:

If $|z_1|^2 = |z_2|^2 = |z_3|^2$, the $c = 0$

$c$ commutes with dilations ( maps of the form $z\mapsto a z + b$, $a$, $b\in \mathbb{C}$, or $z \mapsto a \bar z + b$)

$\bf{Added:}$ The original formula is due to @Christian Blatter:, please check his answer, I only wrote it as a quotient of determinants.

- 56,630

-

1No need to check that commutes with all dilations. It's enough to check that it commutes with translations ($z \to z+b$) – jjagmath Jan 12 '24 at 19:21

-

-

1Writing the formula as the quotient of determinants is no small feat. – jjagmath Jan 12 '24 at 22:34

-