For any $n\geq 0$, the unit $n$-sphere is the space $S^{n}\subset \mathbb{R}^{n+1}$ defined by $$ S^{n}=S^{n}(1) := \left\{ (x_{1}, \dots, x_{n+1}) \;\middle\vert\; \sum_{i=1}^{n+1} x_{i}^{2} = 1 \right\} $$ with the subspace topology. The point $P = (0, \dots, 0, 1)$ in $S^{n}$ called the north pole. Then we have the following conclusion:

$\qquad\qquad\qquad$ For any $n\geq 0$, $S^{n}$ with the north pole removed is homeomorphic to $\mathbb{R}^{n}$.

$\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad$

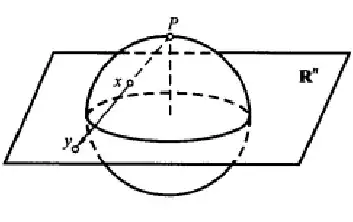

From FIGURE 1-1 ,we define a map $$ f: S^{n} \setminus \{P\} \to \mathbb{R}^{n}, \quad x \mapsto \frac{1}{1-x_{n+1}} \cdot (x_1, \cdots , x_n). $$

(This map is called stereographic projection.)

It can be described geometrically as follows: Given a point $x = (x_{1}, \dots, x_{n+1}) \in S^{n} \setminus \{P\}$, stereographic projection sets $f(x) = y$, where $(y, 0)$ is the point where the line through $P$ and $x$ meets the subspace $\mathbb{R}^{n} \times \{0\}$ at $u = (y,0) = (y_{1}, \dots, y_{n}, y_{n+1})$.

Hence,

$$

\left\{\begin{matrix}

u = \lambda x+(1-\lambda )P \\

y_{n+1} = 0

\end{matrix}\right.

\quad(\lambda \in\mathbb{R}) \Longrightarrow

\lambda = \frac{1}{1-{x}_{n+1}}.

$$

So the analytical expression of the stereographic projection is

$$

f(x_{1}, \dots, x_{n+1})

= \left( \frac{x_{1}}{1-{x}_{n+1}}, \dots, \frac{x_{n}}{1-{x}_{n+1}} \right) \in \mathbb{R}^{n}.

$$

From the geometric intuition,we can get the map $f: S^{n} \setminus \{P\} \to \mathbb{R}^{n}$ is bijective, but how can I prove it theoretically. Further, I need some rigorous proofs that $f: S^{n} \setminus \{P\} \to \mathbb{R}^{n}$ is a homeomorphism. (We must strictly demonstrate that $f$ is injective, surjective, and continuous.)

Another question:

I know the analytical expression of the inverse $f^{-1}: \mathbb{R}^{n} \to S^{n} \setminus \{P\}$ is $$ f^{-1} (y_1, \dots, y_n) = \frac{1}{\|y\|^2 + 1}(2y_1, \dots, 2y_n, \|y\|^2 - 1), \quad \text{where } \|y\|^2 = y_1^2 + \dots + y_n^2. $$ But how can I get this expression?

Who can provide some related materials or solutions about these? (I want use some knowledge of Differential Calculus in Several Variables to solve these questions). Any of your help will be appreciated!