An alternative, fun way to derive a contradiction. I came up with this myself but it's probably well known.

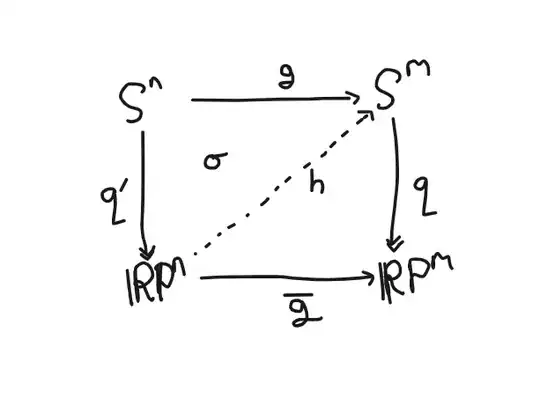

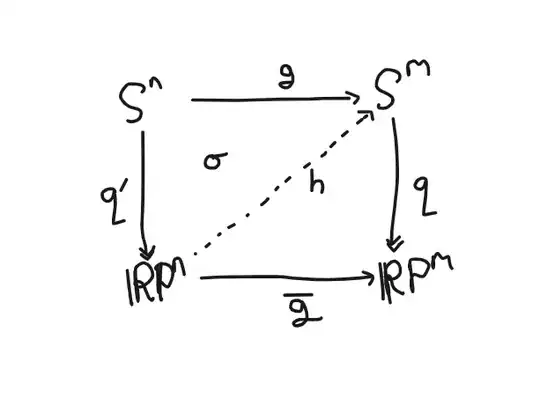

You know that if $n>m\ge 0$ then any continuous function $\overline{g}:\Bbb RP^n\to\Bbb RP^m$ acts trivially on mod $2$ cohomology and hence on the first homotopy group. I explain this at the bottom of the post. If we refer to the lifting criterion discussed in the covering space chapter of Hatcher, we see that $\Bbb RP^n$ is locally and globally connected and $q:S^m\twoheadrightarrow\Bbb RP^m$ is a covering map with $\overline{g}_\ast(\pi_1(\Bbb RP^n))=0\subseteq q_\ast(\pi_1(S^m))$ (with equality in all cases but $m=1$, but we don't need that) so there must exist some lift $h:\Bbb RP^n\to S^m$, $qh=\overline{g}$.

Let $q':S^n\twoheadrightarrow\Bbb RP^n$ be the quotient. We know $\overline{g}\circ q'=q\circ g$ hence $q\circ(hq')=q\circ g$.

By definition of the quotient relation we know $hq'$ and $q$ must differ by some sign; for each $x\in S^n$ let $\sigma(x)\in\{\pm1\}$ denote the relevant sign such that $hq'(x)=\sigma(x)g(x)$. It is easy to argue by continuity of $hq'$ and $g$ that $\sigma$ is also continuous (=locally constant, here). However, $S^n$ is connected $(n>0)$ so $\sigma$ must be globally constant!

Yet $hq'$ is an even function whereas $g$ is an odd function so it is quite impossible for $\sigma$ to be constant. In fact, $\sigma$ is an odd function: $-\sigma(-x)q(x)=\sigma(-x)q(-x)=hq'(-x)=hq'(x)=\sigma(x)q(x)$ so $\sigma(x)=-\sigma(-x)$ for all $x\in S^n$.

We have proven no odd continuous function $S^n\to S^m$ exists for integer $n>m\ge0$.

Explanation of $g_\ast:\pi_1(\Bbb RP^n)\to\pi_1(\Bbb RP^m)$ being the zero map:

Recall the computation $H^\ast(\Bbb RP^k)\cong\Bbb Z/2\Bbb Z[x]/(x^{n+1})$ where $x$ has degree $1$. Let $\alpha\in H^1(\Bbb RP^m;\Bbb Z/2\Bbb Z)$ be the generator and consider $g$ is nonzero iff. $g^\ast(\alpha)$ is nonzero, but observe $0=g^\ast(\alpha^{m+1})=g^\ast(\alpha)^{m+1}$ forces $g^\ast(\alpha)=0$ since $n>m$ and $g^\ast(\alpha)$ is either a generator or zero, and the generator $\beta\in H^1(\Bbb RP^n;\Bbb Z/2\Bbb Z)$ has nonvanishing powers $\beta^k$ for $0\le k\le n$. So, $g^\ast(\alpha)$ is zero. But we know the natural transformation: $H^1(-;\Bbb Z/2\Bbb Z)\to\operatorname{Hom}(H_1(-);\Bbb Z/2\Bbb Z)$ is an isomorphism in this case and this implies that $g_\ast$ is zero on first homology, but also we know the natural map $\pi_1\to H_1$ is an isomorphism ($\pi_1$ of projective space is Abelian) hence $g_\ast$ vanishes on $\pi_1$.