I trying to understand where, as a programmer in situations where it can be good to do a NP-complete reduction to prove that a problem is NP-complete, why is it good to do that as a programmer? I don't understand.

9 Answers

When dealing with a problem, knowing how to recognize a $\mathsf{NP}$-hard problem can prevent you from hair loss trying to find an efficient solution (as it is thought that $\mathsf{P}\neq \mathsf{NP}$).

Reductions can also be seen in a "If I know how to solve $A$, then I know how to solve $B$" way.

When confronted to a $\mathsf{NP}$-hard problem, you can then think of ways to deal with intractability.

- 18,309

- 2

- 30

- 58

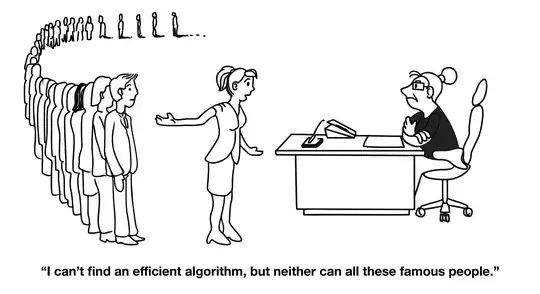

If a problem is NP-complete that means that lots and lots of great mathematicians, computer scientists, and very clever software developers have not been able to find an efficient solution for the problem. And that means nobody can blame you if you can't find one. If you could find one, they'd introduce a Nobel prize for computer science just for you. (Roughly quoted from memory from Garey-Johnson, Computers and Intractability, 1979).

- 32,238

- 36

- 56

Knowing about NP-complete problems is part of the cultural baggage of every computer scientist, as is the case for other core results (such as the non-computability of the halting problem). NP-complete problems arise in practice. The maximal independent set problem for graphs is aimed at simultaneously exploiting a maximal amount of resources that are not dependent on one another.

Theoretical computer science focuses on extremes: problems that are not computable, problems that are too hard to compute (for larger sized instances), limits of computational speed up, limits of compressibility etc. You can interpret these results (from a practical point of view) as guard rails you need to know about in order to make reasonable decisions about new problems. Some of these problems turn up in practice in different guises. The reduction process helps to show that a new problem is NP-complete by linking it (in the chain of NP-complete problems) to a known NP-complete problem. As pointed out in the first answer: when this happens it is reasonable to stop searching for an efficient solution (unless the aim is to resolve the long standing open problems related to NP-completeness).

Theoretical results may appear at times to stay far from practice. They do impact application areas: the halting problem indicated the need to develop real-time programming languages by restricting higher level constructs. The limits of compressibility and running-time speed-up support decisions on when it is reasonable to give up on trying to optimise code for certain applications.

- 622

- 3

- 15

As a working programmer, you need to recognize when you are being asked by the business to do the literally impossible.

Assuming ≠ (you don't need to understand what that means, just know that most of us do), then when you are being asked to solve a problem that falls into NP the solution is going to necessarily be slow (although it may be fast enough in practice).

But if you are told that your map direction calculations for the shortest route that visits cities A, B, C, D, E, and F is too slow, you need to understand that there is a hard bound on how fast it can be.

That's why it's important to understand broadly the sorts of problems in the NP space and why people ask about them (sometimes in disguise) in interviews: you need to be able to recognize immediately that the objective is unachievable and start brainstorming workarounds or trade-offs to hopefully still achieve the business goals.

- 161

- 4

As a programmer, you likely do not need to pay much attention to the class of NP-complete problems. The class of NP problems is much more useful. Obviously, if your problem is NP, it cannot be solved for all inputs in polynomial time (by a deterministic Turing machine, and assuming $P\ne NP$... which is currently considered a pretty darn reasonable assumption)

The easiest way to prove that your problem is NP is to demonstrate that, were you to be able to solve your problem in polynomial time, you could also solve an existing NP problem in polynomial time as well. This is what they mean by a "reduction".

For mathematicians, the idea of NP-completeness is very useful. Completeness says that you can reduce any NP problem to any NP-complete problem. This is very useful for the topic of $P=NP$. If you could find a polynomial time solution to any NP-complete problem, it is trivial to show that you found a solution to every NP problem, thus demonstrating that $P=NP$ without having to mechanically exhaust every last NP problem, one by one, demonstrating that every one of them was infact P.

As a programmer, the best use for NP-complete I have found is to take advantage of the raw amount of effort people have put into exploring good algorithms for dealing with them. I may be working on a problem that's totally unique to my domain, but if I can transform it into another NP problem that people have indeed worked hard on, I may be able to leverage their work. This is especially true for the SAT problems, for which a tremendous amount of work has been done.

As a simple example, in SAT problems, there is often a particularly difficult class of problems that take the form (a|b|c)&(d|e|f)&...&(x|y|z), where a, b, c, ... z are literals (possibly negated), and they aren't all unique (i.e. d may be the same as ~a). In many cases, it is easy to show that the complexity of satisfying that expression explodes as the expression gets longer. But sometimes my problem doesn't call for such expressions. Maybe mine has a limit in how many terms it uses, bounding the exponential growth to something palatable. Maybe each term has no more than one negated term (which makes those Horn clauses -- satisfiability of Horn clauses is in P. In fact, it's linear!).

Sometimes you get lucky and find that, when you do the transformation, you get something really easy (like the Horn clauses mentioned above). In those cases, you might simply figure out what the analog for Horn clauses is in your problem, and just code it up yourself. Other times there's some amazing math behind it, and the easiest way to solve your problem is to actually reduce it to SAT, and solve that.

If I have a problem that is NP, it is NP. I can't leverage other mathematicians to magically make it P. However, often I don't actually have a NP problem. I really have a hard-to-describe subset of a NP problem that I called NP out of laziness or ignorance. If I transform my problem into another, I can also tranform my real inputs. There's a decent chance that my real problem fell within the range of a previously explored P region of a NP problem. SAT, for instance, has been mightily explored. We're actually pretty darn good at finding ways to satisfy many boolean expressions. Maybe an existing SAT solver has a polynomial time solution for all of the reductions of my problem within the limited inputs I need. It's easy to prove they can't solve them all (because SAT is NP), but dang if we haven't made great advancements on many cases!

It's also helpful for demonstrating when I'm not so lucky. If I can take a "hard" problem from SAT, and show that solving my problem requires solving my problem too, then I show one of the following:

- My problem is NP-complete

- My problem requires exploring a P sub-problem of a NP-complete problem like SAT which the state of the art from hundreds of mathematicians hasn't solved yet, or.

- I need to come up with a more clever reduction to sidestep the issue

This does a good job of focusing my attention. Should I really be trying to solve this problem? Is this problem perhaps NP? (even if I haven't proven it formally). Am I capable of finding the more clever reduction? (which, if I can find, shows how I may be able to use the existing proofs for SAT to solve my problem)

Other than that, NP is far more useful for programmers than NP-complete.

Well, maybe. I have found that, when explaining why we shouldn't do something, the term "NP-complete" rings really nicely in people's ears. There's something about the word "complete" that suggest finality, even when your audience doesn't really grasp P vs NP. NP-hard is another useful word, but I find NP-complete does the job really well.

- 3,522

- 14

- 16

To argue in front of your boss.

Source: https://www.ac.tuwien.ac.at/people/szeider/cartoon/

This cartoon is originally from the famous textbook Computers and Intractability by Garey & Johnson, but adapted to the current Zeitgeist.

PS: Concerning the adaption, I would prefer to see real parity here, i.e., having one Alice and one Bob and not Alice two times, but I am not sufficiently talented to modify the cartoon.

- 1,479

- 10

- 15

I once was working as a consulting company where we were writing software for a warehouse management system. One of the requirements was to generate pick lists that would optimize the loading of trucks. My manager came up with an algorithm that he thought would work. It turns out that what he came up with was really just the Bin-Packing Problem, which is known to be NP. He was not familiar with the concept of P and NP, but I was, and I was able to convince him that his solution would not scale, no matter how powerful the computer was that ran the algorithm. This probably save us several weeks of development time. We ended up implementing a heuristic based algorithm that was not optimal, but which worked well in practice.

- 31

- 1

In my sens, Proving NP-Completeness of a problem, can let you try general solutions.

There are some general or maybe efficient (easy to implement and customize, more understandable or representative, scalable, a better parallel version) solutions for any problem. By term "general solutions", i mean interpolation, modeling, approximation, meta-heuristic search algorithms and optimization, ... vice versa.

Using these general solutions is reasonable only if you don't know the true solution or algorithm. So performing a research for proving that a problem is not a NP, or its solution could be approximated by easier algorithms with acceptable result, or it is reducible to some P algorithms, is a valuable effort. This value of this research is depended on use-case (problem), i.e. in a small company it is not valuable.

- 11

- 2

When you decide on a cryptographic scheme you want to know that cracking it is an NP complete problem --- that is, you want the encoding/decoding scheme you want to be as hard as possible to crack. For example, RSA encryption relies on the NP-complete problem of factoring (very large) numbers into their prime factors.

- 11

- 1