The complexity of the BFS and DFS algorithms depend heavily on the graph being analyzed, and the search strategy being used. If we have a method to consistently get "closer" to a solution, then the search can be much more efficient than if we blindly stumble everywhere hoping to find what we need. In this case, I'm going to ignore heuristics for simplicity, and assume that by a BFS solution you mean "blindly try every combination of moves from the start until we find a solution."

The complexity of a BFS over an arbitrary tree with branching factor $b$ and maximum depth $m$ is $O(b^m)$. A branching factor is how many (on average) neighbors there are for every position. The maximum depth is how far we can possibly be from the target position. Some more information on where this fact comes from is available over on StackOverflow.

In this case, the complexity depends on understanding a few things about the puzzle, and the tree that is being searched.

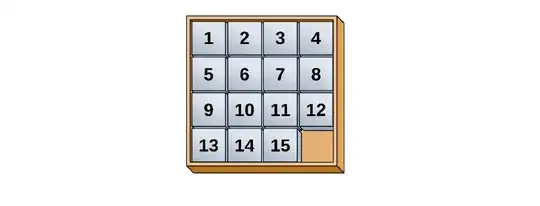

To compute the complexity of a breadth-first search on an $n\times n$ 15-puzzle, we need to know these values.

The branching factor is easier, it's the number of moves we have available. The position can have either 2, 3, or 4 neighbors depending on whether the empty slot is in the center, edge, or corner. There's an exact formula for the branching factor based on how many of these there are. For an $n\times n$ puzzle:

$$\frac{2\cdot 4+3\cdot 4(n-2)+4(n-2)^2}{n^2}=4\frac{n-1}{n}$$

The maximum depth is a little more complicated. The big idea is that for an $n\times n$ puzzle, each individual piece can be at most $2n-1$ positions away from its destination (on opposite corners). On average, if you randomly place pieces on the board, you will get some linear proportion of this value* for each of the $n^2-1$ positions. Multiplying these, we get something on the order of $O(n^3)$.

Putting these two values together, we get that the complexity is:

$$O\left((4\tfrac{n-1}{n})^{n^3}\right)\in O\left(4^{n^3}\right)$$

In practice you can reduce this complexity a bit by choosing a smarter algorithm. For instance, keeping track of visited states to avoid repeated effort will at worst hit the $O(n^2!)$ positions, which is a considerable improvement (at the cost of much worse memory complexity). Heuristic searching reduces this bound by even more, and if we permit finding any solution rather than the best solution, there are algorithms that hit the $O(n^3)$ move bound directly*.

* More information on this can be found in Chris Calabro, Solving the 15-Puzzle, 2005

In this link, it has been told that we can not always find a solution using

In this link, it has been told that we can not always find a solution using