I'm looking for course material on the subject of proofs, reductions, and games, as used to prove cryptographic schemes secure. What are the methodologies? What are the preferred ones? In what cases is it best to use a method rather than another?

1 Answers

The two primary techniques I'm familiar with is structuring a cryptographic primitive as a sequence of games and the universally composable security framework.

Sequence of Games

The idea here is to represent a protocol/primitive as a game played between an attacker and a challenger. You define a bad event and show through the game that the event happens with (close to) some target probability (say 1/2 or 0). For example, if we are modeling an RNG and want to show that the attacker can only guess the next output bit with probability very close to (formally, negligibly close to) 1/2. If they are able to do better than that, then the RNG isn't very good. 1/2 is chosen since there are only 2 choices for the next bit (0 or 1) and they should occur each with probability approximately 1/2 so an attacker who simply always guesses 0, for example, should be right 50% of the time.

The paper I linked to above has some good examples.

UC Framework

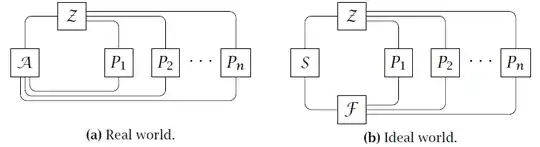

This is a framework proposed by Canetti that sees a lot of use in protocols, especially multiparty computation, but is useful in many situations. The UC framework defines a scenario where we have a real world with an environment $\mathcal{Z}$, an adversary $\mathcal{A}$ and an ideal world with the same environment, a simulator $\mathcal{S}$ and an ideal functionality $\mathcal{F}$. In each world, we also have the participant parties $p_1,\dots,p_n$. The setup is pictured below (taken from Martin Geisler's dissertation):

In the real world, the parties execute some protocol $\pi$, in the ideal world the ideal functionality $\mathcal{F}$ provides the same functionality as $\pi$ but is secure by definition (think a trusted, uncorruptable third party). The UC Security theorem says that $\pi$ securely realizes $\mathcal{F}$ in the real world if there exists a simulator $\mathcal{S}$ in the ideal world such that $\mathcal{Z}$ cannot distingush the two worlds. In other words, if $\mathcal{Z}$ cannot tell which world they are operating in, then $\pi$ must be at least as secure as $\mathcal{F}$. But $\mathcal{F}$ is as secure as possible by definition, so in this case $\pi$ is also secure.

Another cool thing about the UC framework is the composability theorem which says that UC-secure protocols can be composed with other UC-secure protocols (including itself) in arbitrary (even adversary controlled) ways and the resulting composition is also UC-secure. Canetti's paper above has examples.

Reduction

A third technique that is often used is a reduction proof. This is very similar to reduction proofs in theoretical computer science. Basically it says we have some problem $X$ which is hard to break (how exactly that is determined is beyond the scope of the answer, but usually it is that a bunch of really smart people have been trying to break it and haven't). Say I have a new cryptosystem and have shown that breaking my cryptosystem is equivalent to breaking $Y$, i.e., if you break $Y$ you can break my problem. Then, if I can show that breaking $Y$ is at least as hard as breaking $X$, then there is reason to believe my cryptosystem is also secure. For example, see this answer.