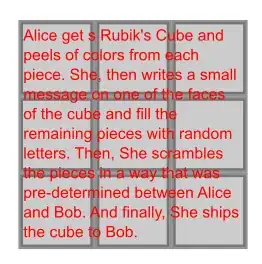

Can this be considered as Encryption

If the sequence of necessary moves is treated as the key, yes.

how secure can this encryption scheme be?

First some details about the cube:

- 6 faces, each with 9 pieces visible each. Because the faces share some pieces, and the immovable cube center is not visible, there are only 26 pieces in total: 6 centers (of faces), 8 corners (each with 3 colored sides), and 12 edges (each with 2 colored sides).

- The center piece of each face is, like the cube center itself, not movable. If it is "moved", in reality everything else moves.

- The 8 corner pieces always are corner pieces, independent of any moves. Same goes for the. 12 edge pieces.

- There are 8! possible position combinations of the 8 corner pieces (naturally). In their position, 7 of the 8 can have 3 possible "rotations", just the last one depends on the others. With this, there are corner $8! \cdot 3^7$ possible corner positions

- Similarly, 12! combinations of edge pieces are restricted to $\frac{12!}{2}$ by the corner pieces (for details to everything, see Wikipedia).

Now, we have 9 pieces that contain "good" data: 1 face center, 4 edges (each has two more sides with nonsense data), and 4 corners (each 1 more side with nonsense data). The other 17 pieces contain only nonsense data.

If an attacker wants to (bruteforce-)find the center piece with the good data on it, there are 6 possibilities (6 face centers, just turning the whole cube around to find the right one).

Then there are 4 corner pieces where position and orientation matters, and 4 others that don't matter to find the one good-data face. Meaning, $\frac{8!}{4!} \cdot 3^4$ possibilities to try here.

Finally, 4 edge pieces where position and orientation matters, and 8 others that don't matter to find the one good-data face. Meaning, $\frac{12!}{2} \div \frac{8!}{2} \cdot 2^4$

Multiplying...

$6 \cdot \frac{8!}{4!} \cdot 3^4 \cdot \frac{12!}{2} \div \frac{8!}{2} \cdot 2^4 = 155196518400$ or about $2^{37}$

Your key has 37 bit. With todays computer, that's nothing =>

completely insecure

Aside from that ...

- A "padding" of 45 byte for 9 byte payload is impractical

- A cube that contains the same symbol multiple times is less secure

- The scheme isn't protected against things like known-plaintext attacks etc.etc.

- Properties like the avalanche effect etc., etc. are completely missing

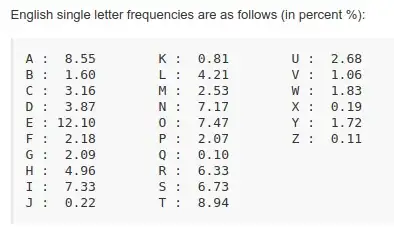

- Depending on the choice of padding data, just making statistics what symbols exist might be enough to figure the plaintext out

- ... and many more