I have a question concerning the pairing of two Bluetooth devices using Simple Secure Pairing with numeric comparison. The NIST document I am looking at states on page 14:

Numeric Comparison was designed for the situation where both Bluetooth devices are capable of displaying a six-digit number and allowing a user to enter a “yes” or “no” response. During pairing, a user is shown a six-digit number on each display and provides a “yes” response on each device if the numbers match. Otherwise, the user responds “no” and pairing fails. A key difference between this operation and the use of PINs in legacy pairing is that the displayed number is not used as input for link key generation. Therefore, an eavesdropper who is able to view (or otherwise capture) the displayed value could not use it to determine the resulting link or encryption key.

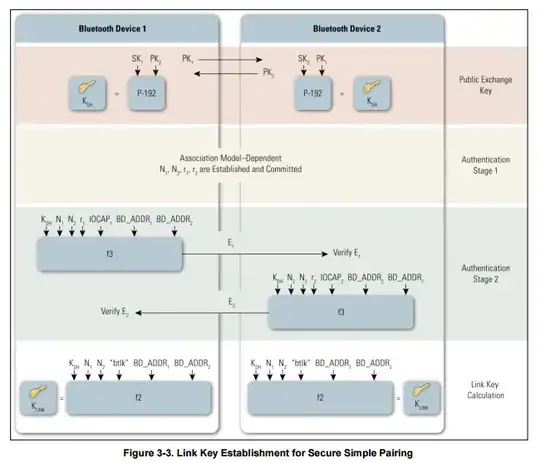

And on page 15, there is a graphic that illustrates the “Link Key Establishment for Simple Secure Pairing”:

Now…

To check on things, I've used a Bluetooth packet capture to sniff the traffic on my phone to see the pairing details. I expected the Bluetooth packet capture to log the details about the $PK$ that was sent and received by the controller. I do see the User Confirmation Request containing the number for the numeric comparison, but I am not able to detect any infos about a $PK$ exchange – as if such an exchange never happened. Therefore, it would be nice to get a confirmation if Simple Secure Pairing indeed uses a $PK$ – and at what point it actually exchanges it.

TL;DR:

I don't understand how the “Link Key Establishment for Simple Secure Pairing” prevents a MITM attack. It seems as if attackers could send a false $PK_2$ nevertheless… or did I miss something?