Disclaimer: I have never taken a cryptography course before. I attempted to work through the problem using what I know from browsing this site and reading a few papers. I hope that by writing this, it might give you a different perspective that may help you in your studies, as well as encourage someone more knowledgeable to swoop in here and give us a better answer.

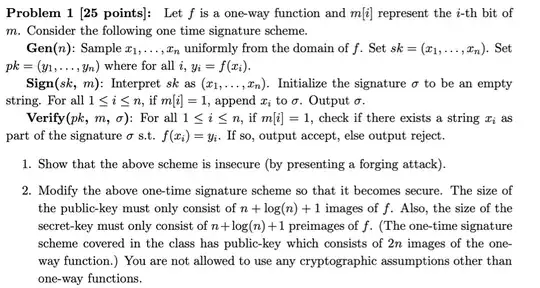

In the original problem, the variables x1, x2, ... , xn are sampled values from the domain of f. That is, they are valid inputs to the one-way function f. The variables y1, y2, ... , yn are the values of x1, x2, ... , xn after running them through f (so y1 = f(x1), y2 = f(x2), etc).

To make things more understandable for myself, I have rewritten "the domain of f" to be the alphabet from A to Z, and the output of f to be the corresponding lowercase letter. This way, the function Gen() produces a nice string of uppercase letters for the secret key sk and a string of lowercase letters for the public key pk, instead of a many "x" and "y" variables. For example, with this modified syntax, Gen(8) would produce an 8-letter output such as "CEIWNGAB" for the secret key, and 8 letters "ceiwngab" for the public key. "C" is equivalent to x1 in the original syntax, "E" is x2, "I" is x3, and so on. The same applies to the letters in the public key ("c" = y1 = f("C") = f(x1), "e" = y2, etc).

Let us see how the problem's one-time signature scheme works using this syntax. We will set n = 4. In this example, Gen(4) uniformly samples the letters from A to Z and conveniently produces "ABCD" as the secret key. As per the scheme, the corresponding public key is "abcd".

Next, we will call the Sign() function using the secret key "ABCD" to sign the message m. Let's say the message is the bit string "1010". In this case, the resulting signature σ would be "AC". This is because the first and third bits of the message are 1, and the first and third letters of the secret key are "A" and "C".

Thus, we have so far:

Now, let's simulate the Verify() function with these values. First, the verifier runs each letter in the signature through the one-way function f. Thus, "A" becomes "a", and "C" becomes "c". Then, the verifier aligns the message to the public key and checks if every letter in the public key that lines up to a 1-bit is present in the transformed signature "ac". "1010" means the first and third letters in the public key ("a" and "c" respectively) need to be in the transformed signature. In this case, they are, so the verifier accepts.

If the signature had only been "A", the transformed signature would be "a", and the verifier would reject since it is expecting an "a" AND a "c".

I noticed that the scheme's Verify() function does not check if the signature includes letters that are NOT supposed to be there. For example, given message "1010", the verifier only checks if "a" and "c" are in the transformed signature. If the signature was "ACXY", the verifier would convert this to "acxy", see that "a" and "c" are in the signature, and therefore accept. If the signature was the entire domain of f-- that is, "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ"-- the verifier would claim any message signed with this signature to be valid. Thus, a trivial forgery attack would be to sign any message with all possible values for the secret key.

This is a little too easy, and also rather preposterous because making the entire domain of f as the signature would cause other issues when applied to the real world (it'd be just a teensy bit big in the context of computer memory). Thus, I suspect this particular answer to part 1 could be outside the boundaries of the problem, or perhaps I misunderstood the scheme and the verifier actually rejects any signature that includes letters that should not be there (i.e. rejects signatures that contain leftover letters after the checking process is complete). If not, this could be a part of your answer for parts 1 and 2.

Otherwise, I agree with your answer to part 1: Have the adversary get a test message of "1111" signed, which produces the signature "ABCD", which is also the secret key sk. Now the adversary can sign any message they want and claim it came from the user with secret key "ABCD".

Let us assume that signing a message with the entire domain of f is outside the boundaries of the problem (or fix it by saying that the Verify() function also rejects any signature that contains letters that should not be there).

Then, for part 2, you have already identified a flaw in the scheme: the secret key is leaked if the adversary can sign a single test message consisting of all 1s. I am not seeing any other problems (note: that doesn't mean there aren't any), so let's try to fix this issue.

What catches my eye is that the size of the public key and secret key must be n + log(n) + 1. Generally, when I see log() functions, the first thing I think of is halving inputs (think binary trees having an average depth of log(n), or the merge sort call stack having a max depth of log(n)).

So, here is my idea:

Generate a secret key sk by sampling n + log(n) + 1 values from the domain of f. To continue the previous example of n = 4, this means the secret key will have 4 + 2 + 1 letters, or 7 letters. Let's say Gen(4) conveniently produces "ABCDEFG".

Produce a public key in the same way as the original scheme, by inputting each letter through the one-way function f. Here, the public key would be "abcdefg".

Sign a message by appending each letter of the secret key that corresponds to the appropriate 1-bit in the message m to the signature σ, just like in the original scheme. However, we also append the additional log(n) + 1 letters of the secret key to the signature according to the following rules:

Count the number of 0-bits in the message, and append the next letter of the secret key only if the number of 0-bits is odd. That is, append the next letter if the number of 0-bits modulo 2 is 1.

Split the message in half (bigger on the left if the bit string's length is odd) and repeat these two steps with the first half of the truncated message and the next letter of the secret key.

(Note: this idea comes from error-correcting codes, specifically "parity bits")

- Verify a message and signature by following the original scheme, accounting for the changes made above.

To give an example of the new Sign() function, let us consider the message "1010" with the secret key "ABCDEFG". First, we would produce a signature "AC" by aligning the 1-bits to the secret key. Next, we would count the number of 0-bits in "1010". There are 2, which is even (2 mod 2 = 0), so we skip adding "E" to the signature. After that, we truncate the message in half and consider the first half "10". There is 1 0-bit, which is odd (1 mod 2 = 1), so we append "F" to the signature and form σ = "ACF". Finally, we split the message one last time and see that the result of "1" means there are no 0-bits (even), and skip adding "G".

It is straightforward to see that this can be replicated using only the inputs of Verify().

Now, if the adversary somehow gets a test message of "1111" signed, they can only divine the first four letters of the secret key ("ABCD" of "ABCDEFG"). If they try "0000", they get "G". They cannot get the full secret key from a single message, because the additional log(n) letters in the secret key are not added if there are no 0s; and if there is a zero, at least one of the first n letters will not appear.

You might say that the adversary could simply sign multiple test messages to piece together the full key. But I believe this is where the original scheme being defined as a "one-time signature scheme" plays a part. A one-time signature scheme implies that re-using the same key to sign a different message discards the security guarantees of such a scheme; therefore, if the signature scheme is being used properly, the adversary will get the letters of a different secret key each time a test message is signed. Supposing I managed to get this right, the adversary would not be able to forge a message under a specific secret/public key without managing to guess the unleaked letters.